Martin Rock’s Residuum

“Open to Revision Mutation”

by Zach Savich | Contributing Writer

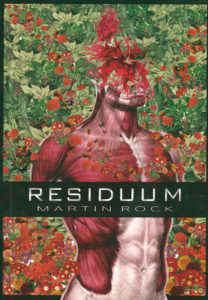

Residuum

Residuum

Martin Rock

Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2016

Martin Rock’s first collection of poetry, Residuum, is a work of what one could call “preserved erasure.” Unlike books that black out or excise text, as though by a whimsical censor’s pen, Residuum uses the straight line of the strike-through to perform enact embody allow its resections to remain apparent. So, a reader sees layered versions, in a manner often available only in poets’ archives. This method might suggest that the unstruck phrases give us the definitive poem, a final draft. Or it could signal that there is no authoritative, underlying poem but only a record of composition. The following lines, for instance, can be seen as three attempts at a three-line section or as a single five-line passage:

To be eternally awake & substantial

in the presence of a womanI met in the ether

I love more than all the feathers on all the ducks

whose very breath is my only hope for air

However, even if you treat these lines as a single passage, their multiplicity emphasizes substitution, not accretion; the “very breath” that is the poet’s “only hope of air” belongs to the woman of the second line, not to the ducks of the fourth, or at least not to both the ducks and the woman simultaneously. And so Residuum’s variations seem to happen in sequence, line by line, unlike works that retrospectively erase a set text. It’s like the poet is continually saying, “No, I didn’t get that quite right, let me try again.” As a result, Residuum’s style of erasure recalls the ways in which poems often refine and recast their statements, or ripple in a reader’s mind. We might read the strike-throughs as saying, “not this, but maybe the next line,” rather than, “this and also the next line, variously and at the same time.”

Thus, Residuum might have more in common with works that simulate a poet’s re-reading or revision than with those that use erasure to convey reticence or suppressed speech; it shows how speech takes place, not the poet’s skepticism about the sayable. In contrast, consider these lines from early in Robert Hass’s “Berkeley Eclogue,” a poem that is conflicted about lyrical utterance:

The bird sings

among the toyons in the spring’s diligence

of rain. And then what? Hand on your heart.

Would you die for spring? What would you die for?

Anything?

The motivating urgency here is clear: each italicized interruption critiques Hass’s efforts at meaningful speech. There’s a related self-critique—and a related concern about linguistic accountability—in Lucy Ives’s Anamnesis (Slope Editions, 2009), a self-revising consideration of identity and loss. “Suppose we write, ‘Paul had a great mind,’” Ives’s book-length poem begins. “Later we can return, strike through the word ‘mind’ and write ‘ brain’ / Later we might add, before the word ‘had,’ the words, ‘the owner of the restaurant.’” The page ends, devastatingly, “Strike the whole sentence.” If Hass’s poem asks us to consider the nature of ethical lyricism, and Ives’s book asks us to think about the difficulties of representation, what questions do Rock’s strike-throughs raise? The beginning of Residuum suggests some answers:

I could find you amongst a pile of leaves

sleeping animals& in the squalor of the overhanging vines

the shade of the hole in the sun

your head

These lines don’t show Hass’s suspicion of poeticism, since “leaves” and “sleeping animals” offer similar kinds of lyrical scenery, and “amongst” seems stylized and slightly archaic, compared to “among.” And they don’t show Ives’s concern about precision, about whether a “mind” might actually be a “brain,” since “the squalor of the overhanging vines” and “the shade of the hole in the sun” seem more like alternates—what I called substitutions—than like specific refinements. Rather, in this case Rock’s revisions seem to glitch the lines away from more predictable meaning: instead of “shade” calling to “sun,” the lines conclude with “the hole in your head.” A bullet hole or other injury? A way to enter the eyes, and the shadow-play of the imagination, where this poem, itself, occurs? However you interpret it, the substitution of “your head” disorients but also extends from the earlier phrases; that is, it doesn’t rupture language or reconfigure image like a Surrealist poem might, but shifts the poem’s vision by a half-step. This change fits the guiding metaphor of Residuum: to let the “genetic material” of language open “itself to revision / mutation.” While the poems by Hass and Ives apply considerations about language to their texts, Residuum seems to try to record the mutations that arise from the text itself as it spoors and unwinds.

This may be why so many of the phrases in Residuum, despite their variations, stay within a similar range. For example, Rock replaces “eat breakfast” with a parallel action—“play hockey”—not with a florid, outlying phrase. He subsequently strikes-through “play hockey” and offers “take part in the infinite.” That phrase matches the others, grammatically, but it’s much more general, since one might take part in the infinite through hockey or a breakfast special. Is Residuum suggesting that “mutation” can tend toward generality, whether of implicit substructures or transcendence? There are many moments when subsequent lines run counter to the typical workshop tenet of “show don’t tell,” instead revising toward underlying abstractions. At one point, for instance, “microscopic robots” become “biomechanical organisms,” which become the even more general “biomechanical intelligence.” Elsewhere, an “official gathering of scientists” is replaced with the “gauntlet of my own imagination.” That phrase erases the specific scene and also folds back on itself, in two senses: it reminds us, again, that the poem is taking place within the imagination, and it does so through a phrase that would often seem redundant (“my own”). Similarly, in the following lines, the strike-throughs soften the specific juxtaposition that turns a whiff of smoke into the entire world, and then soften “the” entire world to “a” single one:

A mere whiff of smoke

The whole world

becomes itself invisible in the mist

This approach to mutation is not uniform. There are times when phrases add specificity or focus—as when Rock replaces several phrases describing actions in the garden, settling on the evocative “sprays the leaves with oil”—but it’s consistent enough to sometimes move the language toward circularity and tautology, as though a mutating phrase seeks to overrun the poem’s expressive system, much as a genetic mutation, or ecological symmetry, can seem to overrun an individual instance. “The reading of thoughts is exceedingly tantalizing,” Rock writes. He replaces the struck-through phrase with “the act in which you are currently engaged,” canceling out both the tantalizing phrase and its tantalizing description of reading. There’s a similar effect in the following lines, which replace a specific action with a more general perception:

In the woods I skinned a bunny

did not skin a bunny

saw a bunny with my own two eyes & pointed out

Look!

The redundancy here seems as significant as patterns do in nature: we don’t only have “my own,” again, but an act of looking depicted three times (“saw,” “pointed out,” “Look!”). Perhaps, then, Residuum suggests that linguistic mutation does not only add to a text but multiplies the effects within it. And there are enough references to the machine-generated (or augmented) experiences of the “selfless” internet and the “sincerity” of pop-up ads to suggest that there’s an algorithmic allusion in this process, though Residuum’s permutations don’t seem to have an overt mathematical basis. Its references to other literary texts suggest that literary production—its absorbed lineages, its relationship to criticism—involves a related form of mutation. For instance, Rock strikes through Berryman’s famous phrase “Nobody is ever missing” and replaces it with “nothing is ever finished.” This paraphrase, like some of those above, is more general than the original line, perhaps suggesting that critical understanding, or the application of memorable phrases, can become reductive, while still leaving a specific trace. But it also, once again, brings the text to comment on itself, on its potentially endless revisions. Through this method, Residuum suggests that linguistic mutation might help us migrate through “plains / pages / internet” to reach an “incorporeal mind” that lives within and through our language. It almost makes it feel wrong to speak of authorship; the strike-through can feel more geologic than personal, a striation on a cliff’s side, a fault line underfoot.

—

Zach Savich‘s most recent books are the poetry collection The Orchard Green and Every Color and the memoir Diving Makes the Water Deep. He teaches in the BFA Program for Creative Writing at the University of the Arts, in Philadelphia, and co-edits Rescue Press’s Open Prose Series.