With What Words; With What Silence?

by Maia Evrona | Contributing Writer

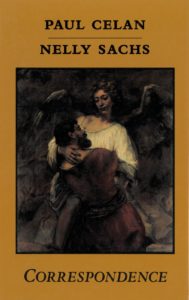

The German-language, Jewish poets Paul Celan and Nelly Sachs began corresponding in 1954 and continued writing to each other until their deaths in 1970. These letters are collected in an English-language edition entitled Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs: Correspondence (Sheep Meadow Press, 1995), translated by Christopher Clark and edited by Barbara Wiedemann. While their friendship is known of, and it is widely acknowledged that Sachs—whose work was not widely available in the United States for many years though she won the Nobel Prize in 1966—was influenced by Celan, and that Celan, in turn, was influenced by Sachs, these letters make plain that similarities between the work of Celan and Sachs date to before their discovery of one another. Much of this similarity can simply be accounted for by their subject matter: both wrote in response to the Holocaust.

The German-language, Jewish poets Paul Celan and Nelly Sachs began corresponding in 1954 and continued writing to each other until their deaths in 1970. These letters are collected in an English-language edition entitled Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs: Correspondence (Sheep Meadow Press, 1995), translated by Christopher Clark and edited by Barbara Wiedemann. While their friendship is known of, and it is widely acknowledged that Sachs—whose work was not widely available in the United States for many years though she won the Nobel Prize in 1966—was influenced by Celan, and that Celan, in turn, was influenced by Sachs, these letters make plain that similarities between the work of Celan and Sachs date to before their discovery of one another. Much of this similarity can simply be accounted for by their subject matter: both wrote in response to the Holocaust.

Paul Celan was born in 1920 in Czernowitz, Bukovina—a region that is now split between Romania and Ukraine. Celan grew up speaking German, not Romanian, as did many middle-class Jews throughout Central Europe. During World War II, Bukovina was passed from Romania to Russia, only to be invaded by the Germans. In 1942, when Celan was twenty-two, his parents were deported to Transnistria, a region by the Black Sea, where his mother was shot and his father died of Typhus. Celan passed the war in work camps.[modern_footnote]John Felstiner, Paul Celan; Poet, Survivor, Jew. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001)[/modern_footnote] He later immigrated to Paris, where he married the visual-artist Gisele Lestrange, and had a son, Eric.

Following his parents’ death, Celan suffered from mental illness, which worsened over the course of his life. He drowned himself in the Seine in 1970, at the age of fifty. His poem, “Deathfugue,” is the most famous poem to emerge from the Holocaust:

Black milk of daybreak we drink it at evening

we drink it at midday and morning we drink it at night

we drink and we drink

we shovel a grave in the air where you won’t lie too cramped[modern_footnote]Paul Celan, Selected Poems and Prose of Paul Celan. trans. John Felstiner (New York, London: W.W. Norton, 2001)[/modern_footnote]

Nelly Sachs was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin in 1891, twenty-nine years before Celan. Sachs and her mother were able to escape Germany and immigrate to Sweden in 1940. Though she published poetry before World War II, it is the Holocaust-focused poetry that Sachs wrote after fleeing Germany that built her reputation and for which she was awarded the Nobel Prize. In Sweden, Sachs was plagued by physical and mental illness characterized by persecution mania, which she simply called fear. She, too, died in 1970, at the age of 79 and of cancer, on the day that Paul Celan was buried.

Sachs’ book In the Habitations of Death, contains a poem entitled “O the Chimneys.” This poem strongly echoes “Deathfugue,” though Sachs had not yet read Celan when she wrote it, nor would Celan read her poem before writing his own:

O the chimneys

On the ingeniously devised habitations of death

When Israel’s body drifted as smoke

Through the air—

was welcomed by a star, a chimney sweep,

A star that turned black

Or was it a ray of the sun?[modern_footnote]Nelly Sachs, O The Chimneys; Selected Poems Including the Verse Play, Eli. trans. Michael Hamburger, Christopher Holme, Ruth and Matthew Mead, Michael Roloff (Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America by Arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967)[/modern_footnote]

Though the first letter of their correspondence is no longer extant, one can piece together the chronology of the first letters from later statements made by Celan. In the literary journal Documents, he discovered Sachs’s poem “Chorus of the Stones”:

We stones

When someone lifts us

He lifts the Foretime—

When someone lifts us

He lifts the Garden of Eden—

When someone lifts us

He lifts the knowledge of Adam and Eve

And the serpent’s dust-eating seductionWhen someone lifts us

He lifts in his hand millions of memories

Which do not dissolve in blood

like evening.

For we are memorial stones

embracing all dying.

It is likely that Celan then wrote the poem “Whichever Stone You Lift,” in direct response to “Chorus of the Stones”:

Whichever stone you lift—

you lay bare

those who need the protection of stones:

naked,

now they renew their entwinement.Whichever tree you fell—

you frame

the bedstead where

souls are stayed once again,

as if this aeon too

did not

tremble.Whichever word you speak—

you owe to

destruction.

One can read this last stanza as an artist’s statement: throughout his poetry, Celan tried to find meaning within destruction, not in rising above it. In Celan’s world, silence and destruction had to be trudged through in order to create poetry, for he saw silence as the other necessary half of a word.

Celan then wrote Sachs asking her to send him her second book, Eclipse of the Stars. He also asked his publisher to send her his book Poppy and Memory, which contains many of his most famous poems, such as “Deathfugue” and “Corona.”

We can’t know exactly what Celan wrote in his first letter, but we can guess that it was polite and respecting, as many of his first letters to Sachs are. Upon beginning their correspondence, Nelly Sachs emerges as a far more compelling letter-writer and personality than Celan. Not only are her struggle with mental illness and the poems that emerge after each of her breakdowns moving, but her letters also exhibit eccentricity and passion. For as much as his friendship with Sachs seemed to mean to Celan, he does not divulge as much regarding his own feelings, and many long periods go by in which he does not write at all. However, as one reaches the later letters, the differences between the ways Celan and Sachs responded to their respective trauma and mental illness, and their attempts to reach out to one another amid great personal pain—as well as the periods of silence between those attempts—emerge as the most compelling quality of their collected correspondence.

Sachs’ letters contain an outpouring of emotion from the very beginning, when she writes to Celan after receiving his book:

Dear Poet Paul Celan, now I have your address from the publisher and can thank you personally for the deep experience that your poems gave me. You have an eye for the spiritual landscape that lies hidden behind everything Here, and power of expression for the quiet unfolding secret— . . . I, too, must walk this inner path that leads from “Here” towards the untold sufferings of my people, and gropes onwards out of the pain.[modern_footnote]Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs, Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs; Correspondence. trans. Christopher Clark; Ed. Barbara Wiedemann; Introduction by John Felstiner (Riverdale-On-Hudson, New York: The Sheep Meadow Press, 1995)[/modern_footnote]

With this last line, I believe Sachs is responding to what she found in Celan’s poems, rather than the content of his first letter. Celan was seemingly content to continue connecting solely through their work; he did not write her again for another three years, and then only with an exceedingly polite letter soliciting poems from Sachs for an issue of the journal Botteghe Oscure, which he was co-editing:

I thought immediately of your poems, gracious madam. Would it be possible for you to send me some unpublished material by January 10?

I have acquired your new volume of poems: it stands, with the two others, among the truest books in my library.

However, except for the line calling Sachs’s books some of the truest books of his library, Celan doesn’t approach any of Sachs’s writing about the “inner path that leads from ‘Here’ towards the untold sufferings of [their] people, and gropes onwards out of the pain.” Despite this, Sachs tells him that his letter was “one of the great joys of [her] life.” She goes on to write:

There are notes and poems from my time of doom lying hidden, just ways of rescuing breath from suffocation. And then came your dear, tender words, and they were a reason to seek things out, write them down and enclose them with this letter.

To this Celan does respond:

You do not know how much it means to me to receive poems from you yourself, accompanied by such amiable lines, and to be able to pass these poems on.

This response inspires a nearly two-page letter from Sachs, in which she insists Celan finally call her by her name instead of Madam, and she writes:

There is and was in me, and it’s there with every breath I draw, the belief in transcendence through suffusion with pain, in the inspiritment of dust, as a vocation to which we are called. I believe in an invisible universe in which we mark out our dark accomplishment. I feel the energy of the light that makes the stone break into music, and I suffer from the arrow-tip of longing that pierces us to death from the very beginning and pushes us to go searching beyond, where the wash of uncertainty begins.

Sachs also describes her feelings about being awarded a prize for her work from the Swedish Academy, despite being a foreign-language poet who had been forced to flee her native country. She ends by saying that she doesn’t know how much longer she will be able to write for—a striking comment considering that she wrote for another fourteen years until her death. This letter from Sachs manages to draw Celan out:

When your letter came the day before yesterday, I wanted most of all to get into the train and travel to Stockholm to tell you—with what words, with what silence?—that you must not believe words like yours can remain unheard. Much heartspace has been submerged, yes, but as for the legacy of solitude of which you speak: because your words exist, it will be inherited, here and there, as the night is spent. False stars fly over us —certainly; but the grain of dust, suffused with pain by your voice, describes the infinite path.

It is worth nothing that, at this time, Paul Celan was in the midst of an extra-marital love affair with Ingeborg Bachmann and this lengthier and more passionate (though platonic) response mirrors an extraordinary increase in frequency and intensity in his letters to Bachmann (See: Correspondence, by Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan, translated by Wieland Hoban). Sachs’s letters may have reached Celan at a point when he was most open to being reached, enhancing an emotional state that had already begun. This could explain why Celan did not respond to Sachs’s letter from three years prior.

From this point on, Celan and Sachs proceed with a familiarity that seems surprising for how recently their correspondence has started. One must consider that their relationship began with their poems and their letters took it to a new level. Both no doubt felt isolated by being Jewish poets writing in German outside of Germany, and after the Holocaust. Both believed greatly in the power of words and of poetry, but could only fear that their work was falling into a void. Their logical, primary readers were Germans and Jews who spoke German, but they risked alienating their German audience by writing about the Holocaust, while they risked alienating Jewish readers by writing in German. For Jews, during World War II, German went from being the language of writers and philosophers—many of whom were Jewish—to being the language of Hitler. In one of his poems, Celan writes:

And can you bear, Mother, as once in a time,

The gentle, the German, the pain-laden rhyme?

At the time that Celan and Sachs lived and wrote, it was assumed that they were part of the last tiny handful of Jewish poets who would ever write in German. The speed of their connection attests both to their loneliness and to the great need both of them felt to communicate through poetry. A poem, Celan said, is “sent out in the—not always greatly hopeful—belief that somewhere and sometime it could wash up on land, on heartland perhaps.” For Celan to tell Sachs that he considered her work to be “true” was not a light compliment.

By the time Celan and Sachs began corresponding they had lost their parents and had little immediate family, though Celan was married with a child. Many people they had known in their youth had been murdered; the community in which Celan grew up barely existed. Sachs addresses Celan as her brother:

Dear brother and friend Paul Celan,

May the New Year be blessed for you and yours! With your poems you have given me a homeland that I had thought at first would be seized from me by death. So I hang on here.

Sachs often includes poems with her letters. One such poem has the refrain, “Oh hear me—” Celan responds: “I hear you.”

In 1960, Nelly Sachs was awarded the Droste literary prize in Germany. She stayed in Zurich, and traveled to Germany only to accept the prize. Celan met her there and she then visited him in Paris on her way back to Sweden.

It is often assumed that the persecution manias of Celan and Sachs reinforced one another. I am unsure of the extent to which this is true, if true at all. In their letters to one another—those not written under the influence of mania—both Celan and Sachs exhibited an awareness of being plagued by delusions, and Celan was certainly aware that Sachs was mentally ill. Sure, Celan does write to Sachs about the anti-Semitism he sees around him, particularly in his negative reviews, and in some of the earlier letters, he seems to be overreacting enough to border on delusional, but it is also understandable that both poets would have been hypersensitive to anti-Semitism. An example of severe delusional mania is this letter that Sachs writes Celan six years into their friendship, not long after their first meeting:

Paul my dear,

just a few quick lines

A Nazi spiritualist league is using radio telegraph to hunt me with terrifying sophistication, they know everything, everywhere I set foot. They tried with nerve gas while I was traveling. Been in my house secretly for years, listening with a microphone through the walls, so I want to give Eric a part of the compensation money, the other part is to go to Gudrun in my testament, that’s why I am writing so hastily. I have the proceeds from my parents’ property to give away. The testament has to be altered as quickly as possible.

One can assume that the worsening of Sachs’s mental health was most likely triggered by traveling to Germany to accept the Droste Prize. Celan wrote her this letter:

You are feeling better—I know.

I know it, because I can feel that the evil that has been haunting you—that haunts me also—, is gone again, has shrunk back into the nothingness where it belongs; because I feel and know that it can never come again; that it has dissolved into a little heap of nothing.

So now you are free, once and for all. And I too—if you will permit me this thought—am free beside you, with you, as we all are. I am sending you something here that will help against the little doubts that sometimes come to one; it is a piece of sycamore bark. You take it between the thumb and the index finger, hold it very tight and think of something good. But—I can’t keep it from you—poems, and yours especially, are even better than sycamore bark. So please, start writing again. And let us have something for our fingers.

Sachs was hospitalized. Celan tried to visit her but was asked by her doctors to only stand in the doorway. This was the last of the three times they saw one another in person during their sixteen-year-long friendship. Nelly Sachs either didn’t recognize him or couldn’t acknowledge him, then. But she continued to write to him. In fact, after the initial letters, she stopped waiting for a reply: sometimes as many as seven letters from Sachs will come before a response from Celan. Nelly Sachs was terrified of silence: over the years, her poems became shorter, lost titles along with punctuation, and began ending in dashes, making each poem seem prematurely cut-off and also a continuation of the last, as if to prevent any silence from coming between them. In the editorial afterword to Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs: Correspondence, Barbara Wiedemann, points to the lack of punctuation in this sentence as evidence of Sachs’s panic at the thought of silence:

The most terrible thing had happened to me and I can’t find the words to say what in truth was behind the thing that brought me within a hair of mental and physical ruin.

Though Sachs never truly shakes her fear, she does make a kind of triumph over her fear of wordlessness simply by continuing to write poetry, though her letters to Celan diminished in frequency over time. As the correspondence goes on, there are often only around four letters from Sachs per year, a number that like a lot because of how few letters there are from Celan, and because of the greater openness in Sachs’s letters. When she does write, she describes her state of mind, her life, asks for a letter back and includes a poem:

When the great terror came

I fell silent—

fish with the dead side

turned upwards

air bubbles for the struggling breathAll words fugitives

to their immortal hiding places

where the conceiving power must spell out

its star-births and time mislays its knowledge

in the riddle of light—Paul—Gisele—Eric

I am homesick for you!Back in the apartment again after years of hospital.

The sycamore bark letter is the only time Celan speaks of the evil that “haunts [him] also.” While he expresses anger over anti-Semitism, he never describes his own depression and thoughts of suicide. He never writes Sachs the desperate letters she sends him. He never mentions his own hospitalizations, and never informs Sachs when he and his wife decide he should live alone. Perhaps he did not wish to burden Nelly: his letters describing difficult visits to Germany and negative reviews stop after her breakdown—though this was a time when he became increasingly demanding of other friends, and a time in which his illness showed through in other correspondences. From then on most of his letters to Sachs read like this:

Dear Nelly,

we are happy to hear from you yourself that things are better again, that you are working. You are often present in our conversations.

I received the Signs in the Sand and read it most attentively, as I do everything that comes from your pen. —I thank you.

Allow us all to wish you good things and true!

On a superficial reading, it might seem as if Celan is only writing back to help someone he knows needs contact, without extending himself too much, rather than writing out of his own need. However, Celan did write to Sachs spontaneously. In addition, Celan kept every letter Sachs ever sent him. He also kept the envelopes, as well as carbon copies of his own letters and his unsent drafts. In Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs: Correspondence, this letter, which he wrote on the Jewish New Year in 1961, is included as if it had been sent:

It has become very lonely around us, Nelly, we are not having an easy time. But I hope that for us, too, things this year will be different from the last.

It is noted, at the back of the book, that this is a draft that was never sent.

In December 1964, Celan sends a letter marking the anniversary of their friendship:

Soon it will be eleven years that we have known each other, and a great deal has happened in these years, much of which you foresaw. In a few days a new year will begin—may it bring you joy, happiness and all fulfillment. Warmest greetings, from Gisele and Eric too.

The draft version shows much deeper feeling than the letter that was sent:

Ten years ago, or, more precisely, ten-and-a-half years ago, I had written to you after reading [In the Habitations of Death] to ask if you could let me have a copy of [Eclipse of the Stars]. Then we exchanged letters, not a few of them, then you came, then you fell ill, then I came because you had called me to Stockholm.

For the last few letters of the correspondence, Sachs and Celan return to a more normal pattern, with two letters from Celan, two letters from Sachs, and a last letter from Celan. In Celan’s second to last letter, he tells Sachs that he has just been in Israel and heard that she had been released from one of her many hospitalizations. He writes of his own work, and says that he longs for a letter and new poems from her. She fulfills his request. The last letter from him comes with no date. He presumably wrote it not long before his suicide. All it says is: “All gladness, dear Nelly, all light.” Both of these letters are evidence of the misleading stage of suicidal depression in which it seems as if the sufferer is emerging from his illness when he is actually manic and most dangerous.

It was frustrating, for me, as a great lover of the work of Paul Celan, to see the lack of deep feeling and forced happy face in many of the letters he wrote to someone who seemed to be so important to him, though I value the letters in which Celan affirms the power of poetry. Paul Celan wrote lines like “It’s time the stone consented to bloom,” and “Trust the trail of tears / and learn to live.” It may be true that, in the case of Nelly Sachs, Celan had realized that Sachs was too unstable for him to truly depend on. This realization may have been painful, reinforcing the isolation he already felt. One must also consider that the books collecting his letters to and from Gisele Celan-Lestrange (still only available in French), Ingeborg Bachmann, and Ilana Shmueli—all women with whom he was involved romantically–are far longer than the collection of his correspondence with Sachs—striking considering that his correspondence with Shmueli largely took place over the course of just one year. This is not to say that Celan neglected Sachs because he was not in love with her–or, worse, that he was some kind of ladies man—and these women also wrote to Celan more often than Sachs did.

Still, reticence and long periods of silence are a feature of all of Celan’s correspondences published in English translation. In his poetic vision: “every word you speak / you owe / to destruction,” and over the years, silence and destruction came to have a greater hold, making it more difficult for him to reach the words on the other side. His poems became increasingly sparse: less focused on stringing words along a musical line that delivers meaning as a whole but rather on endowing single words with great meaning, frequently combining words to make them more powerful. Often, in Celan’s later poems, one or two words constitute a whole line. These later poems are powerful, albeit sparse and difficult. Celan did succeed in balancing silence when writing poetry, but, perhaps, poetry was the only forum in which he could. The silences in his correspondence with Nelly Sachs may be evidence of the silence he contended with in his work. Then again, though he often apologizes for his lapses in letter-writing, Celan may have truly felt that he was in a kind of communication with Sachs, even when he wasn’t writing letters, for she continually told him that she was reading his poems, as he affirmed the worth of hers—a way of meeting that was, perhaps, always stronger than writing letters.

Paul Celan wrote a poem after he met Nelly Sachs in Zurich at the Stork Hotel:

Our talk was of your God, I spoke

against him, I let the heart

I had

hope:

for

his highest, death-rattled, his

wrangling word—Your eye looked at me, looked away,

your mouth

spoke toward the eye, I heard:We really don’t know, you know,

we

really don’t know

what counts.

—

Maia Evrona is a poet and prose writer. Her poetry has been awarded a grant from the Fulbright Scholar Program and appeared in numerous venues. She is currently completing a memoir on chronic illness and periodically publishes essays and opinion pieces. She also translates literature from Yiddish (and occasionally Spanish) into English. Her translations of the Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever were awarded a fellowship in translation from the National Endowment for the Arts.