Through The Digital Looking Glass

by William Bernhard | Web Editor

Author’s Note: The following piece is based on things I scribbled in a notebook this past summer while in Rome where I found myself face to face daily with artifacts both living and dead. My observations are related in an off-hand way to John Berger’s seminal television series “Ways of Seeing,” all of which you can find on YouTube.

Through The Digital Looking Glass

1: Anno Domini

Pictures aren’t worth a thousand words—they operate in a different dimension. Photos attempt to literally cast a moment into a reproducible experience, one that is supposed to seem true because we are led to believe that we are seeing exactly what the photographer saw and what he or she experienced in that moment. Nothing needs to be spoken or written—we’re inclined to believe we are witnessing something. In our contemporary era of digital photography (this includes video as well) we can now witness people’s lives moment by moment. It’s as if we’re all living on the set of any given reality TV show at any given moment thanks to web sites like YouTube, Flickr, and Facebook.

Wander the prison-esque, Stendhal syndrome inducing corridors of the Vatican Museums most summer days and you’ll find yourself navigating around large groups of headset wearing tourists storming room after room en masse with their arms outstretched like digital camera wielding Scyllas. Treasure after treasure is viewed primarily through small glowing screens before the naked eye takes them in unassisted—it’s as if an LCD display somehow makes the experience more real. Has it become easier to process something once it has been reduced to its digital simulacrum?

By contrast words exist in the ear and the mind’s eye. If I take an out of focus picture of the Sistine Chapel’s painted ceiling how can it possibly describe the way Michelangelo’s famous painting seems to hover below the surface its painted on, or how it appears to glow? The other thing that is lost is the sense of the painting’s immensity, which is enhanced by the size of the room it’s in and its distance from the floor. Not even the professionally created books and DVD’s available in kiosk after kiosk inside the Vatican Museums capture the vastness of Michelangelo’s ceiling; it’s as if God himself is up there whipping the nine stories from the Book of Genesis to life. Trying to capture this photographically renders each painted panel into a specimen floating in digital formaldehyde.

Describing the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel or the feelings it induces remains difficult. In contrast to photographic dissections, I feel what Waldemar Januszczak experienced when he persuaded someone to allow him access to the scaffolding during the restoration of Michelangelo’s hovering frescoes, which he describes in an article written for the Sunday Times in 2006: “I sneaked up there a few times. And under the bright, unforgiving lights of television, I was able to encounter the real Michelangelo. I was so close to him I could see the bristles from his brushes caught in the paint; and the mucky thumbprints he’d left along his margins.” In fifty words Januszczak details a literally more intimate, fascinating look at the paintings then would ever be possible in video because words exist solely in the mind; so much is at the mercy of the reader’s imagination and the writer’s ability to communicate his or her thoughts that the stakes seem much higher than the ones regulated through a digital display.

Despite all this it seems that a picture is still worth a thousand words and my sentiments, like American readers of poetry, exist in the minority. The very idea that words live only in their imagined ether makes them harder to access in our world of one minute news cycles and thirty seconds of internet fame. But this leads to a question: do a thousand and one words suddenly become truthful? It seems at the root of “a picture is worth a thousand words” (a statement coined by advertisers during the last century) lies the sentiment that words are not to be trusted; if I show you a picture or a postcard of God zapping Adam’s finger with the Holy Static Electricity something more truthful is revealed than exists in any written or spoken description. Something believable. Yet we still begin and end our days immersed in language: it lies at the core of who we are; it is how we define ourselves. Every thought, every feeling, every gesture—we process these things through the invisible power of language. Digital imaging cannot replace this.

Despite all this it seems that a picture is still worth a thousand words and my sentiments, like American readers of poetry, exist in the minority. The very idea that words live only in their imagined ether makes them harder to access in our world of one minute news cycles and thirty seconds of internet fame. But this leads to a question: do a thousand and one words suddenly become truthful? It seems at the root of “a picture is worth a thousand words” (a statement coined by advertisers during the last century) lies the sentiment that words are not to be trusted; if I show you a picture or a postcard of God zapping Adam’s finger with the Holy Static Electricity something more truthful is revealed than exists in any written or spoken description. Something believable. Yet we still begin and end our days immersed in language: it lies at the core of who we are; it is how we define ourselves. Every thought, every feeling, every gesture—we process these things through the invisible power of language. Digital imaging cannot replace this.

2: Ante Christum

Once, when right after her marriage to Augustus, Livia was on a visit to her villa at Veii, an eagle flew by and snatched a white hen, which was clutching a sprig of laurel in its beak, and at once dropped the bird into her lap. She decided to rear the hen and plant the sprig. The hen produced such a quantity of chicks that today the villa is known as “The Henhouse,” while the laurel grew to such a size that, whenever the Caesars were about to celebrate a triumph, they would gather laurels from it.

-Suetonius from “Galba” in Lives of the Caesars.

On the outskirts of Rome in the suburb of Prima Porta (“first door”) lies the remains of Livia’s Villa (the site’s namesake, Livia Drusilla, was the wife of Caesar Augustus and the most powerful imperial Roman matriarch). The villa was the empresses’ summer home of sorts, the place she escaped to when the noisy and gossipy confines of Rome became too much for her.

As you wind your way up a trash strewn road into a park, it’s hard to tell that anything is there at all besides large verdant trees and hills baked tan by the sun. Eventually the path leads you towards a fenced off area entered through a small building that’s equal parts guard house and tiny museum dedicated to Livia’s Villa. After passing through this modest shack you make your way down a wide dirt road cut through the middle of a hill and then you come upon what appears to be a white, Mid-Century modern style picnic shelter looking like it should appear in the pages of Atomic Ranch magazine. This structure instead of housing Italian picnickers protects the remains of Livia’s Villa (and the archeologists who work there) from the weather. The white rectangular structure also acts like a schematic, allowing you to see the probable floor plan of the villa and provides the illusion that you’re actually stepping inside it. In reality, where the lavish second home for the queen of Rome once stood now lies crumbling walls framing the footprint of rooms, some of them partially tiled with mosaics detailing the empress’ favorite mythological scenes. The entire space is a perfect intersection between the ancient past and the present, which aren’t as far apart as we’d like to believe.

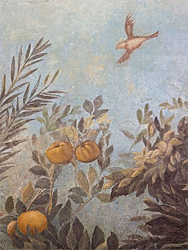

The one building at Livia’s Villa that remains intact (or has been restored to look this way) is the site of her triclinium, accessible through a staircase descending into musty dimness. Once inside the room you’re faced with a series of wraparound life-sized photographs reproducing the frescoes that once covered all four walls: the paintings depict a panoramic bricked-in garden filled with fruit bearing trees, plants in bloom, and countless birds in various stages of flight. The distant landscape is visible as well, but it’s blurred by a fog, making the triclinium feel as if it’s the one spot blessed by the sun. Luckily, the original paintings are not lost. They’re on display at the National Museum of Rome where they’re installed inside a room that’s a replica of the one they were taken from—the real things are inside the fake thing and the fake things are inside the real thing.

The day after visiting Livia’s Villa I went to the museum to see the replicated triclinium. This imitation room containing the real paintings felt less alive to me than the actual room with the life-sized photographic reproductions of the same frescoes. Surely this had to do with the fact that the the National Museum of Rome’s version of the room is temperature controlled, complete with full spectrum lights that cause every bird, shrub, and fruit in Livia’s frescoes to glow equally. Somehow this made the real paintings in the fake triclinium feel false to me in the same way an enormous butterfly with radiant blue wings pinned to a felt board and mounted behind glass feels false: it is no longer a part of its natural context, but an ornament on display.

Adding to the strangeness was a light-show, quietly announced on a small placard discreetly placed next to the room’s entrance: every hour on the hour the lighting in Livia’s replicated triclinium wheels through the entire cycle of daylight in a matter of minutes. The process begins when all the lights suddenly dim down to pale orange, representing morning. This causes certain species of the painting’s birds and trees to flare to the forefront as if they were peering in at you from some Elysian world. Then as the “day” progresses other aspects of the painted garden fade in and out of the foreground— color doesn’t exist without light and different colors metamorphose depending on the type and quality of light they’re exposed to; the way Livia’s frescoes seemed to shift and glide as the lighting changed made this apparent.

The oddest part of the pseudo-triclinium’s light-cycle is when it reaches mid-day: the glow in the room feels stabilized, yet the eye continues to sense the subtle variations in the lights as they shift towards their programmed twilight. During these moments I began to question whether or not the display was done, or maybe it had malfunctioned. Things seemed off—the shadows of the ropes keeping visitors a safe distance from the frescoes seemed to shift slightly; the “midday” whiteness of the room had the quality of equilibrium regained after an unexpected head-rush—everything seemed normal yet simultaneously out of sync . Then, the lights shifted towards a deepening orange. As indifferently as the display had begun, the overhead lights providing it glided back to white. This brightness surely could never reach into the real triclinium half-buried underground in the outskirts of Rome. Standing inside the reproduction of that room made me feel like I was in the closing scene of 2001: A Space Odyssey in which Dave Bowman lands his spaceship inside infinity’s baroque, white chamber and an entire future plays itself out onscreen in a matter of minutes.