While We Can Sing

by Elsa Valmidiano | Contributing Writer

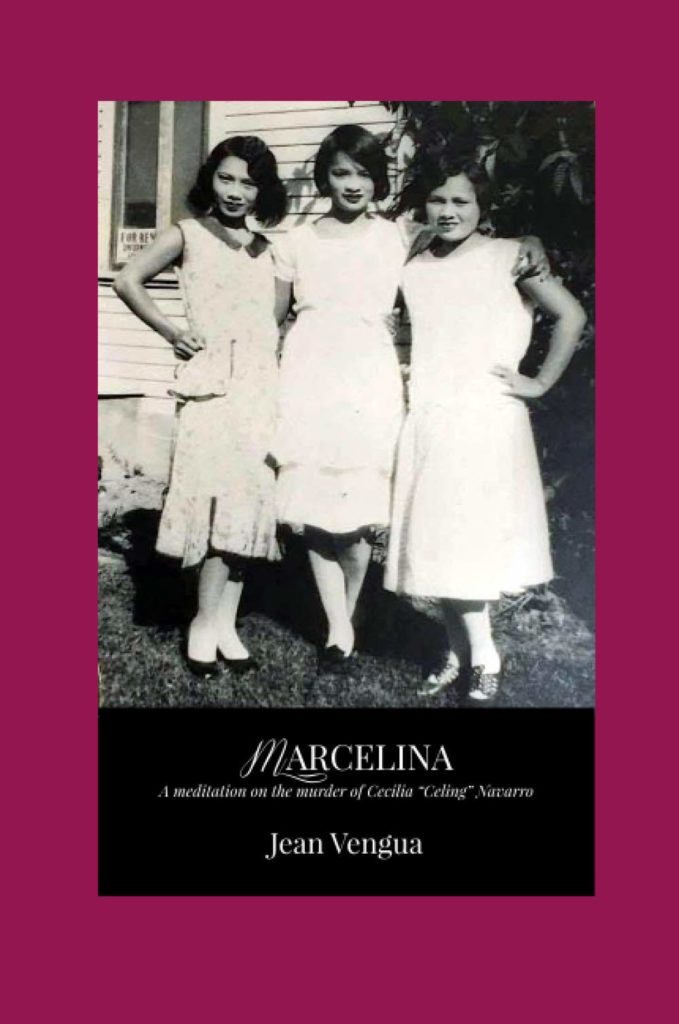

Marcelina

Jean Vengua

Paloma Press, 2020

Jean Vengua, a daughter of the Manong generation, was born in San Francisco, raised in Santa Cruz, and lives in Monterey. Marcelina, a long epic poem recently published as a chapbook, begins with a quote from Carlos Bulosan: “And perhaps it was this narrowing of your life into an island. . . .” For those unfamiliar with Bulosan, he is what a Filipino-American pupil might call the Godfather of Filipino-American Literature. Bulosan is honored for writing about the experiences of Filipinos working as laborers in the US during the 1930s and 40s, when Celine Navarro, a young Filipina immigrant—the subject of Vengua’s book—was murdered by her Filipino community. The reasons behind Navarro’s murder are never made clear in Marcelina, but in it Vengua takes the reader through an extended examination of that era’s Filipino community in the US, revealing the terrorism and violence inflicted on the community by white society. She reveals, as well, the misogyny within a Filipino community that resulted in Navarro’s death: members of her own community buried her alive as punishment or retribution for either being an adulteress or informer to the police. Eighty-nine years after her death, still none of us know the reason for it, a mystery which is further compounded by the lack of historical accountability for the terrorism inflicted on the Filipino community, as well as the acquittal of Navarro’s killers.

In 1932, Filipinos in Northern California lived on the margins; whites terrorized Filipinos with blatant discrimination, mob violence, and the torching of entire Filipino towns. This is the setting of Marcelina. To fully appreciate Vengua’s book, one must understand the societal and historical circumstances leading up to Navarro’s murder—what led to the insular conditions of a Filipino community in the first place, and the psychology behind why the community that Navarro belonged to felt compelled to kill her. Considering the Filipino community’s own marginalization, one would surmise that the Filipino community in Northern California existed back then under the protection and laws of their own micro-government—their own island, as Bulosan called it—and in order to exist as law-abiding citizens under that micro-government, you had to obey their laws, whatever those laws might be, because where else were you supposed to belong when you are rejected outright everywhere else?

The different fonts Vengua uses throughout the book indicate actual newspaper text juxtaposed with poetic imagery that vividly illustrates the conditions Navarro lived and died in—the timeless rural landscape in which she was literally buried alive, alongside the ongoing, over-arching racism that plagued the Filipino community at large. As the fonts weave between Times New Roman (for the newspaper text) and Arial (for Vengua’s own poetry), there arises a natural comparison between the terrorism inflicted by white society on the Filipino community and the terrorism that a patriarchal Filipino community inflicted on their own, a practice in which even other women would punish a woman in the interest of upholding that patriarchy. Vengua’s work pushes a psychological narrative, not just of Celine Navarro, but of an entire community—after it’s suffered so long that its actions become self-destructive, turning violently on itself.

Through direct quotes from different local newspapers, Vengua shows the inflammatory language used to sensationalize Navarro’s murder and the defendants at her murder trial:

. . . the most barbarous and most inhuman

crime ever recorded in the criminal

annals of the State of California.

An irony arises where Vengua uses her poetry, noted in Arial font, where the newspapers of the day obviously failed—as a journalistic tool which manages to evoke Navarro acutely, tenderly (rather than sensationally):

Not just the men; she was here,

smelled the black earth, pear blossomings

manure and fresh hay; reads the morning

paper, steam on the windows,

thinks of her sisters, married, distant.

wonders: what will I do today—strip the bed,

cook rice, write a letter, say thanks be to God

Vengua’s imagery is intimate and visceral and contrasts with the language of the newspapers that, on top of a general lack of due diligence, fail to properly state the victim’s name. Celine Navarro is “Mrs. Celina Nava,” “Mrs. Cecile Nama,” “Marcelina Nava,” “Mrs. Nava,” “Mrs. Navar,” and “Celine Novarro.” She is reported as pregnant, not pregnant, an adulteress, and/or a snitch to an assault and kidnapping. Even after her death and during the murder trial, the newspapers perpetually blame the victim.

At the end of the poem, the newspapers seem to enjoy creating a ghost story out of the folklore of her murder, moving completely away from factual reporting to fantastical news:

“I was horrified to see walking a short

distance away the white shadowy form

of a woman whom I recognized at

once as . . .”

What Vengua does is fight a battle to bring us back to the facts, despite the little we know of them. Instead of getting lost in the business of parsing the details of contradictory and incomplete newspaper reports, Vengua brings us back to the subject herself; the reader is placed within Navarro’s own body as she was buried alive:

how the dead must wrestle,

wrench from the ground some light

for the journey back to the surface. the lucky

float downstream

turn their milkfish gaze to the sky; loose and easy

they are carried, until the rigor sets in, some looking down

into the ruins of the oceanthe riverbed

the catch basin where they wait

with open hands.

There’s an undercurrent working throughout the poem; it reveals the marginalization of the Filipino population in California at the time, when newspapers were unabashedly flippant in their reporting, characterizing the defendants as either Filipino gangsters, bootleggers, or a cult. You don’t just feel the othering. You see it clearly written out in newspaper headlines.

Sprinkled throughout the poem, it’s easy to see the self-prophesizing nature of newspaper headlines to influence society’s violent repercussions against Filipinos after coverage of Navarro’s murder:

October 9, 1933

A dynamite blast early last Wednesday morning

partially wrecked a bunkhouse on Hennessey Ranch,

between Gilroy and Hollister, imperilling 30 Filipino

pea pickers who were asleep inside. [It] is attributed

to an anti-Filipino agitation which has been brewing

in the district.

This is only one such example, though there are many instances Vengua provides as evidence of bigotry and terrorism against Filipinos following Navarro’s death.

Facts about Navarro’s murder remain a mystery in Vengua’s poem, though what is made clear is the negative perceptions American society had toward Filipinos where they are continually othered and demonized by the headlines: “Seven Indicted by Jury in Voodoo Live Burial” and “California Gets View of Primitive Tribal Justice.”

Vengua is of my parents’ generation, but she was born and raised in California, unlike my parents, who were born and raised in the Philippines and immigrated in the 1970s like much of the Filipino-American population I am familiar with today. Vengua’s parents would have known about Celine Navarro; she would have known about her too, if her parents or family friends ever mentioned Navarro. Navarro’s murder might have become scary folklore for my generation if we’d ever heard about her. But I never did.

That I only very recently discovered Navarro’s story is indicative of the persistent silence that continues to enshroud Filipino-American society. I grew up in a predominantly Filipino-American LA suburb in the 1980s, and Navarro is someone I’d never heard of until now. While Navarro’s story is painful and it feels shameful to consider what a Filipino community did to their own, it is necessary to honor Navarro’s memory as well as break the silence surrounding the trauma inflicted on Filipino workers and their communities during Navarro’s time. If we don’t speak about Celine Navarro, we not only forget who she was, but we also risk forgetting the sacrifices and self-determination of our Filipino immigrant communities then who struggled and survived in the face of racism, violence, and injustice. As Vengua puts it:

the brain ticks,

a watchworks running down

all these things, today’s news, casting off the web’s

infinite and dreadful arc, and the catch:

the names, singing the names (say to ourselves)

while we can sing, talk while we can talk; tell it

eventoourselves.

—

Philippine-born and LA-raised, Elsa Valmidiano is a writer and poet who calls Oakland home. Her works have appeared in various literary journals and anthologies. Elsa is an alum of the DISQUIET International Literary Program in Lisbon and Summer Literary Seminars hosted in Tbilisi. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Mills College. She has performed numerous readings throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. The daughter of Filipino immigrants and an infant immigrant herself, her writing oftentimes explores the ways we exist and interact on the personal and community level, given the circumstances of her Motherland’s disappearing traditions in her adopted country. WE ARE NO LONGER BABAYLAN (New Rivers Press, 2020) is Elsa’s debut essay collection.

Jean Vengua is a California-born-and-raised writer, poet, and visual artist who grew up on its beaches and sunny avenues. She is the author of Prau (Meritage Press), The Aching Vicinities (Otoliths Press), Corporeal (Black Radish Books), and Marcelina (Paloma Press, 2020). A meditation on the murder of Celine Navarro, Marcelina has been recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize. With Mark Young, Jean co-edited the First Hay(na)ku Anthology (Meritage Press, 2005), and The Hay(na)ku Anthology Vol. II (Meritage Press, 2008). Her poetry and essays have been published widely in journals and anthologies.