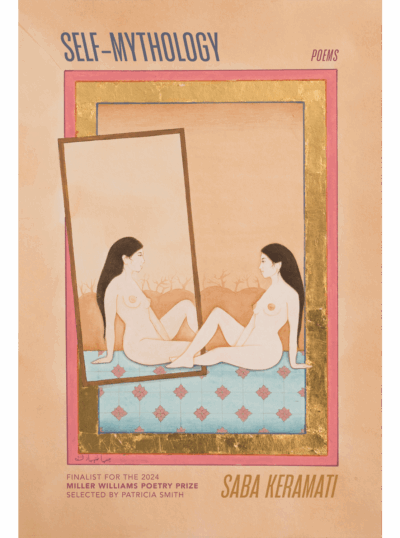

What’s The Difference Between a Person and a Prayer?: On Saba Keramati’s Self-Mythology

“What have I inherited?

Is it salt?”

I choose to begin with these opening lines of Saba Keramati’s poem, “Questions for the Outward Curve of My Stomach, Where I Sometimes Rest My Hand and Pretend to Be Pregnant” because it looks simultaneously at the lineage of the past and the fable of the future. The speaker goes on to inquire, “Where does it all go, if I don’t have a daughter?”—a question the collection hinges on. Whether this daughter is concept, alter ego, myth, or offspring, we don’t learn, and it doesn’t matter. What matters is the poet’s yearning for a descendant, a subject through and to whom to pass on her history and heritage.

In her preface, Patricia Smith, who selected the collection as the winner of the 2024 Miller Williams Poetry Prize, describes Self-Mythology as “the book we need right now, as so many of us explore our hyphenated selves, searching for meaning in being not all one and not all the other, wondering if and where we are truly rooted.” What does it mean for the self to be hyphenated? Does it mean that one’s sense of identity is split, or that this split-ness empowers one to fashion a self that is greater than the sum of its parts? This lingering sense of (be)longing resonates deeply with me, as I am sure it does with other immigrant daughters. In “The Infinite Potential of Wrong Directions,” Asa Drake asks, “How much of our conversation is an attempt to enter a history without feeling alone?” I enter this particular conversation as a lost individual, an unmoored boat. As we keep asking these questions, I realize I am only a drop of water in this tumultuous ocean of identity politics, the separations of the personal and the political, conflicted ideals of how to assimilate and how to resist.

Keramati does not promise any answers. She, instead, holds a torch up to the parts of ourselves we keep sheltered. In “Self-Portrait Alone in the Kitchen,” the speaker touches on occupying space, domesticating oneself, and questioning one’s hunger:

“I train myself to starve. I grow soft

instead of smaller”

and then, towards the end of the poem:

“When my stomach growls,

I imagine it is eating itself, it is eating me,

it will make me thin like my mother.”

This isn’t the only place where the ghost of the maternal figure appears. In “What Remains,” she writes, “My mother did not believe in heaven and so I did not believe in heaven. I did not believe in heaven so when I prayed it wasn’t to god.” Throughout the collection, the speaker grapples with how much of her mother she grows into, how much she retains, how much she sheds. This dichotomy also invokes her to interrogate the reliability of memory. In “My Aquarius moon won’t let me rest,” she writes, “I’m forced to wonder what forgetting means, if I can be reminded so easily.” If one cannot separate one’s own, distinctly created, memories from those borrowed from others, how does one establish the idea of self, with belonging, with ancestry? This contradictory preoccupation returns the speaker toward the notion of embodied memory, “What else has gone wandering deep in this body, what else has slipped from memory?” These poems work through the tension between wanting to trust one’s own, and by extension, one’s loved ones’ memories when examining the authenticity of one’s being (a woman, a body…) and, in doing so, invite readers to pause and introspect on what vessels we rely on–not only as individuals, but also as generations–to claim our unique histories, how our bodies are living relics of these stories.

On the process of knowing and naming the collection, and also one’s relationship to faith and religion, Keramati shares in an interview with The Offing, “I knew what I was writing about before I had its name.” This statement is reflected in how the speaker’s consciousness oscillates between reverence and its lack throughout the journey of the book. In “Invocation,” she asks, “What’s the difference/ between a person and a prayer?” ending the poem with an invocation of a future self, the conceptual daughter we encountered earlier. Does this daughter arrive in a physical form? We do not know for sure. Is the speaker’s god a physical entity? We do not know that either. Finding god (in one’s body, in exchanges between lovers, in dreams of mothering) is the central thread that braids the speaker’s ideas (and claims) about politics, men in power, organized religion, deceit, and a sense of worldly detachment. In “Ars Poetica Ghazal,” she resists colonial expectations of obedience and hierarchy,

“I think myself alive and so I am. So I open

against authority, to think I matter.”

What is this form of opening that Keramati emphasizes? Is it expanding ourselves to the world(s) that we are a part of? Is it leaning on our communities–and if so, what are these communities and how does one name oneself as a part–? Is it an unconditional trust in the body and its knowledge of the ancient? Or, is it creating a whole new truth, a myth altogether? This collection doesn’t boast of excavating the truth, it only places its desires and secrets in the reader’s hands. It is aware of the impact and lineage of loaned language and collective vocabulary. Although these feelings are well-reflected in the array of forms in the book, one particular form that stuck out for its decolonial use was the Cento, especially in the way Keramati utilizes it as a tool for looking outward at diasporic literature while highlighting the insecurities and struggles an individual might face even when surrounded by community. In “Cento for Loneliness & Writer’s Block & the Fear of Never Being Enough, Despite Being Surrounded by Asian American Poets III,” she writes,

“I hold things I cannot say in my mouth—

I’m a poem someone else wrote for me.”

In this conundrum, this multiplicity, a figure the speaker returns to, over and over again, is the proverbial daughter. Is this daughter a cartography of all the daughters past, a chronology of wounds? Is she a collection of fragments (and thus the unreliability) of memory? Is she a fabricated version of the speaker’s self, a portrait of all matrilineal errors? When history fails a daughter over and over again, where does she go? Who shields her? I don’t have a simple answer. I picture this daughter as a symbol for all things better, more hopeful, and will continue thinking of her as I daughter myself out of generational grief and shame, etching Keramati’s words (from “Self-Portrait with Womanhood”) to memory–

“I feel like a girl again. The water rises.

I am still my own daughter.”