by Joannie Stangeland | Contributing Writer

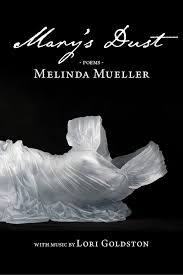

Mary’s Dust

Mary’s Dust

Melinda Mueller

Entre Ríos Books, 2017

Readers of Melinda Mueller’s earlier collection What the Ice Gets: Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition, 1914-1916 are familiar with her keen storytelling skills and ability to shape historical research into an intimate, human experience. Mueller now offers us Mary’s Dust, a series of poems that traces a succession of Marys through history. In these poems, whether in the first or third person, women give their own accounts. With empathy and a scientist’s precise attention to detail, Mueller exhumes these stories from silence, as in the book’s opening poem, “Annunciation,” which confronts the conventional narrative of the Virgin Mary, noting “That story was // conceived years later by men / who had not been there.”

Masterfully, Mueller wields form and language to bring forth each woman and her individual circumstances. In “Moll Cutpurse Sings the Blues,” Mueller employs a ballad meter and the slang of the times to give Mary Frith a swaggering defiance:

Bing close, my darling partridges,

Bing close as all you can,

Look close as you may please, partridges—

See you a woman or man?

In another poem, Mary Wortley Montagu, the British letter writer and poet of the early 1700s, speaks in the long, contemplative line of the ghazal:

The ambassador’s recalled. From jasmina-scented stars and honeyed sun,

Lady Mary goes home to grey. Each month a scimitar moon pricks her heart.

In “Maria Sibylla Merian,” the repetition of the sestina emphasizes the painstaking, cyclical nature of scientific experimentation, which befits the naturalist Merian, whose engravings of insects draw them “in time lapse, from egg to butterfly, having raised / them in boxes full of leaves.”

However, Mueller doesn’t relying solely on standard poetic forms. She also experiments formally based on the context of her subjects. “The Lost Gospel of Maria Aegyptica,” a woman who spent 40 years wandering naked in the desert, is set in chapter and verse, while “Mariah the Copt” is in fragments. Time itself becomes a form in “Mary Easty,” whose visceral story travels backward from being “ferried / over the River Jordan at last / in the mouths of ants,” detailing her body’s decay in her reverse, ending in her jail cell the night before her hanging in Salem. “The Witch,” a poem about Maria Gaetana Agnesi, the mathematician who discovered the Agnesi curve, is structured as a geometrical proof. Mueller frames “Testimony,” a poem about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, as courtroom proceedings, and presents the Typhoid Mary poem “Mary Mallon” as stage directions, with chorus segments taken from historical texts. Mary Cassatt’s poem is written in a block of text, as the world blurs after she loses her sight, and “strikes her now that she had filled her works with mirrors, as if she knew she must double all she saw, before she was forsaken of all seeing…”

The manner that Mueller employs notes in the collection creates a kind of doubling. For example, “Ledger,” a poem about September 11, 2001, mentions not a single Mary, yet in the notes Mueller lists the names and ages of all the Marys who died that day. For other poems, the notes allow Mueller to fill in details behind the subjects of her poems, relieving the poems themselves of the need to provide context and backstory. In the poem “Mary Anning,” we learn that Anning was a fossil hunter who “did so enjoy an opposition amongst the bigwigs” and was “first to pry an ichthyosaur from the Blue Lias”; the notes reveal that she was “probably the subject of the tongue twister, ‘She sells seashells by the sea shore’.” In the poem “Salt, a Slave Narrative,” we read

lips salty arms salty breasts dripping brine

my soul is salt trying to flee from my bodyfor the soul is a free thing it hates its fetters

In the notes we learn that Mary Prince was also a writer, that her autobiography was “among the earliest published firsthand accounts of the life of a slave.” We learn of Marie Colinet, a midwife and renowned surgeon who saved lives even while losing seven of her eight children to the Plague, and then we learn of her silence—nothing is known of her after the date her husband died.

The collection closes with “Requiem for Sister Mary Makukutsi,” a seven-part poem that weaves Bemba-language prayers, texts from Charles Darwin and Wallace Stevens, and the landscape and folklore of Zambia. The image of the whirlwind in the first section, “Introit,” evokes the “robes that streamed and whirled / in a wind that filled her ears” in the collection’s opening poem. Now, the swirling wind “let fall the leaves // and sept up a cloak of ash” then “turned to naked // ghost shaking one mopané tree”. The “Offertorium” begins and ends with the question, “What shall we offer as ransom, Lord, / for the safety of her soul?”

In the poem’s final section, “In Paradisum,” the words of the prayer are spread out across the page like the “thousands of // red billed queleas come // flocking out of the veld”, like “the Dead // in their scattered / parts”, the “roiled molecules the air riven”. The richness of the imagery speaks to a depth of both grief and celebration, while the expanse between the phrases illustrates the breaking down of everything to the elemental, to dust, as “Thousands of / silences // fall.”

Joannie Stangeland is the author of In Both Hands and Into the Rumored Spring from Ravenna Press, and three chapbooks. Her poems have also appeared in Prairie Schooner, Mid-American Review, The Southern Review, and other journals.