Thinking Like a Mountain: On the Centennial of Marianne Moore’s “An Octopus”

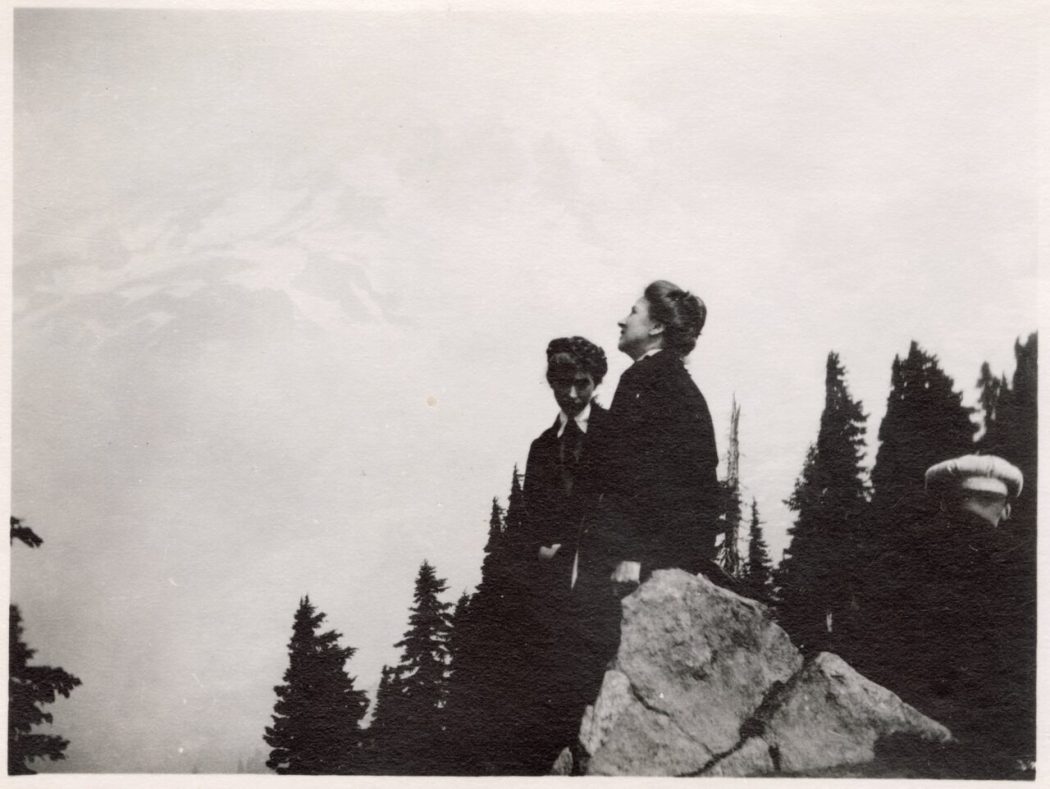

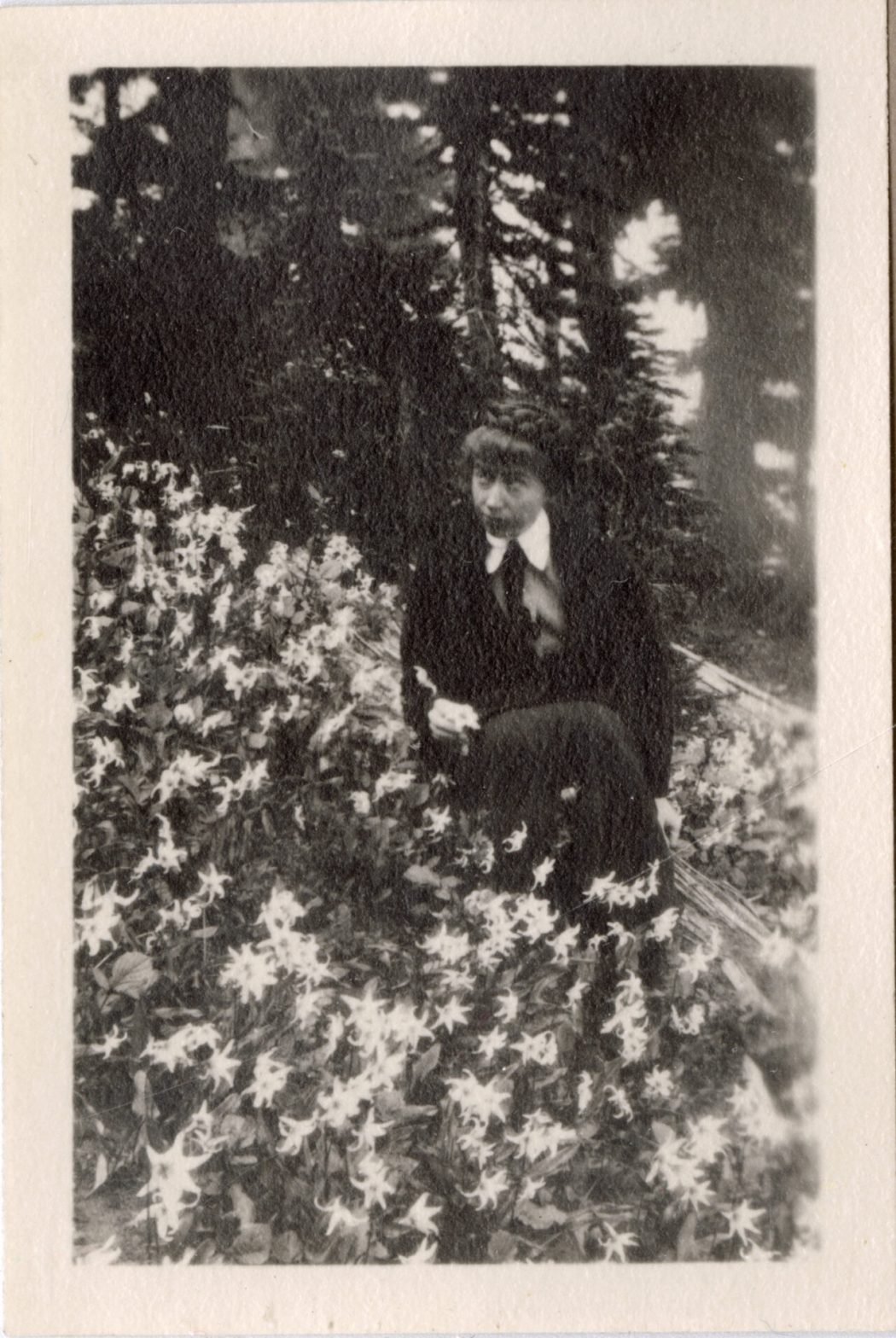

In 1922, Marianne Moore traveled by train with her mother from New York City to Washington State to join her brother for a trip to Mt. Rainier National Park. That journey is what prompted Moore to compose “An Octopus,” which borrows its title from the National Park Service’s name for the system of glaciers atop Mt. Rainier, which, when seen from above, resembles an octopus. At 193 lines, the poem is the second-longest Moore would ever publish (“Marriage” is the longest), and the most ambitious. While the poem’s length is a result of Moore’s catalog of the physical features and inhabitants of the Mt. Rainer ecosystem, her poem is not simply a list poem. It is an early ecopoem which delves into the interrelationship between the other-than-human features of landscape while interrogating human attitudes toward nature. In short, the poem, to borrow a phrase from 20th Century environmental philosopher Aldo Leopold, thinks like a mountain.

When a poet’s chosen subject is nature or, specifically, the earth’s ecology, the poet faces the artist’s usual challenges. Does she favor a representational approach faithful to the facts of the setting? An expressionist response to nature’s stimulus? Some combination of the two? A representational approach has its limitations: a mere catalog of species and biological processes may make a fine biology textbook but not a fine poem. List poems, too, when presenting a biological inventory, run the risk of losing voice. On the other hand, a fully expressionist response to the subject is necessarily centered on the author’s singular perspective which may forfeit a universal perspective. The compromise? A bent toward scientific fact over speculative thought when facts are readily available.

Does that mean a poet needs to be a scientist to write a good ecological poem? Not necessarily. But a commitment to research or scholarship helps. Marianne Moore was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College, and although she earned her degree through a combined program in history, economics, and politics, she preferred biology and took at least one course in that field. As we see in “An Octopus,” she did her research. Moore relies on, and incorporates, outside texts to inform the ecology of the poem. The texts quoted by Moore (identified by footnotes in the version of the poem included in the Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry) include such unexpected sources as the 1922 United States Department of the Interior publication entitled Rules and Regulations: Mount Rainier.

In considering the representational and expressionist balance of the poem, direct quotation favors the representational. But what adds dimension to the poem, even in the absence of the “I”, are the ways in which the speaker adds commentary. For example, consider lines 14-24 of the poem (here the “appropriated” text has been italicized for emphasis):

The fir-trees, in ‘the magnitude of their root systems’,

rise aloof from these manoeuvres ‘creepy to behold’,

austere specimens of our American royal families,

‘each like the shadow of the one beside it.

The rock seems frail compared with their dark energy of life’,

its vermillion and onyx and manganese-blue interior expensiveness

left at the mercy of the weather;

‘stained transversely by iron where the water drips down’,

recognized by its plants and its animals.

Completing a circle,

you have been deceived into thinking that you have progressed.

The reference to “American royal families,” assigns regal status to the firs, an expressionist act. A deeper stamp of authorial intent appears in the observation that things have a tendency to come full circle and that we as readers and members of modern society may be deceived that we have progressed. This theme receives clearer emphasis later in the poem, specifically in the second half, starting at line 161, where Moore undertakes the comparison of Greek and Christian moral philosophies (as discussed by Patricia Willis in “The Road to Paradise: First Notes on Marianne Moore’s ‘An Octopus,’” which examines the poem through the lens of Moore’s papers held at the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia).

One of the advantages of art over pure biological inventory is that it helps to place nature in perspective by engaging the subject in conversation, or at least in an evaluative thought process on the part of the poet. This thought process becomes conversation when the poem engages a reader and the true act of thinking comes in. A poem, though it may be set in a specific ecological place, becomes a modified ecosystem once the poet and reader inhabit the poem. As defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, an ecosystem is: “A biological system composed of all the organisms found in a particular physical environment, interacting with it and with each other. Also in extended use: a complex system resembling this.”

“An Octopus” expands the ecosystem of Mt. Rainier beyond its physical boundaries by infusing the poem with human presence in the form of philosophy and commentary. In terms of ecology, within the first portion of the poem, through line 160, Moore catalogs the following living inhabitants: periwinkle; fir trees; larches; bears; elk; deer; wolves; goats; ducks; porcupine; rat; heather; beaver; ant hills; berry bushes; goat; mountain guide; trapper; water ouzel; ptarmigan; heather bells; alpine buckwheat; eagles; marmot; spotted ponies; frosty grass and flowers; birch-trees; ferns; lily-pads; avalanche lilies; Indian paint-brushes; bear’s ears; kittentails; fungi; rhododendron; Larkspur; blue pincushions; blue peas; lupine; aspens; cat’s paws; wooly sunflowers; fireweed; asters; Goliath thistles; gentians; lady-slippers; harebells; mountain dryads; Calypso (the goat flower); mountain climbers; and blue jay.

Other living entities appear metaphorically: octopus (of ice); python; spider; cypress; antelope; bristling puny swearing men equipped with saws and axes; grasshoppers of Greece; Adam (from the Bible) and Henry James (the novelist). What are Adam, Henry James, and those so-called grasshoppers of Greece doing in a poem about Mt. Rainier? What Moore has done is populate the poem not only with a variety of texts, which create an echo effect of voices against the mountainside, but also more distant, ghostlike figures. This expands the scope of the poem by an order of thousands of years. Normally this would have the effect of dwarfing the current inhabitants of Mt. Rainier, but Moore so thoroughly catalogs contemporary ecology that they maintain agency as they cohabit the ecosystem with these past worlds. Starting with line 161, “An Octopus” veers from the mountain into the mind by incorporating a comparison of Greek and Christian moral philosophy. According to Patricia Willis, one of the key criticisms made by Moore with respect to Greek philosophy is its preference for the ecosystem of the mind over the actual ecosystem of earth. Moore shares her perspective on the Greeks in “An Octopus” (lines 162-68):

the grasshoppers of Greece

amused themselves with delicate behavior

because it was ‘so noble and so fair’;

not practiced in adapting their intelligence

to eagle-traps and snow-shoes,

to alpenstocks and other toys contrived by those

‘alive to the advantages of invigorating pleasures’.

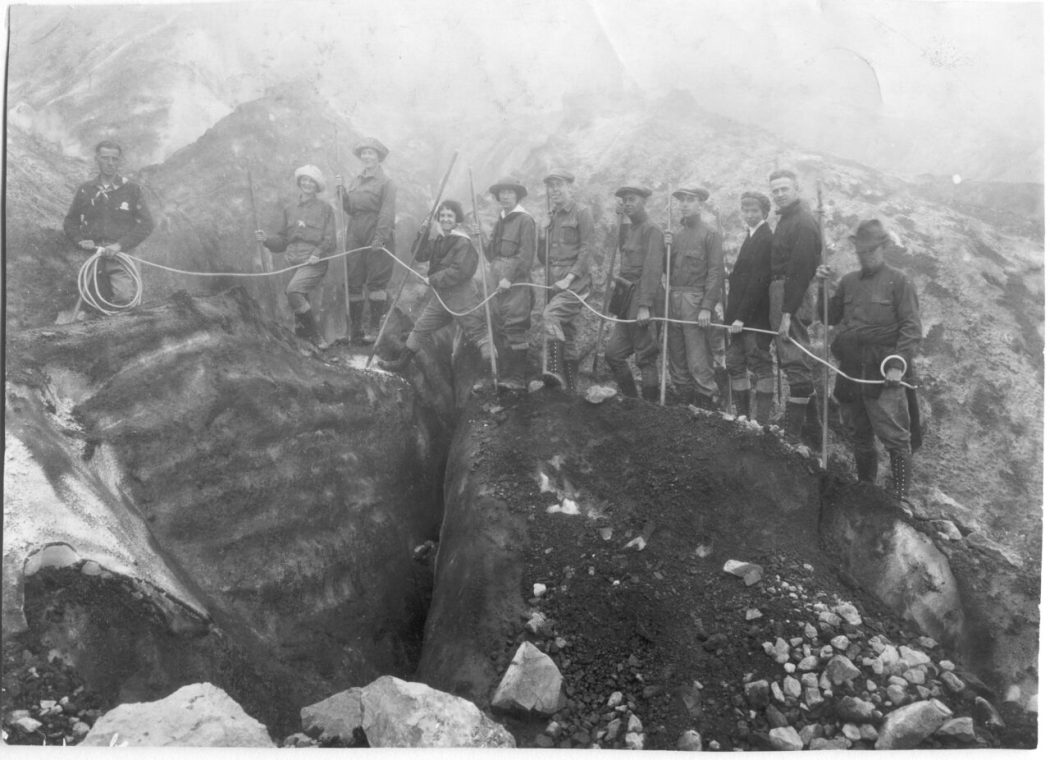

Of course, excellent poetry can spring from the imagination (think Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan”), but Moore’s position is compatible with contemporary ecopoetics theory, which seems to advocate for what I would call a poetry of witness or direct experience. The “eagle-traps” referred to in Moore’s poem, also known as crampons, are ice cleats used for walking on glaciers. Moore understands that the poet needs to strap on ice cleats or snowshoes and directly experience and truly understand the octopus of ice. In fact, she can be said to have walked the talk: a photograph uncovered by Patricia Willis in the archives of the Rosenbach Museum shows Marianne Moore and her brother John climbing ice fields on Mount Rainier equipped with the necessary climbing gear.

Ultimately, to express what it means to “think” like a mountain requires creative energy beyond the mere cataloging of the mountain’s attributes. Did Moore’s “An Octopus” build its own ecosystem and therefore think like a mountain? The only way we can express thought in a work of art, even if we attribute that thought to a mountain, or lake, or cloud, etc., is by thinking ourselves. We have no choice but to think as humans in order to translate the mountain. What Moore’s poem does successfully in terms of the sheer ecological challenge of truly presenting a mountain is build a biological inventory of life on Mt. Rainier derived from various sources. She then necessarily modifies that catalog by introducing the concept of human thought, specifically (per Willis) by delving into the realm of human philosophy. In the end, however, she commits to letting the mountain speak its own truth.

“An Octopus” may be considered an early ecopoem, one that contemporary poets may wish to study, and celebrate. Poets may also want to adopt Moore’s technique as her process presents one solution to the problem of how to avoid anthropocentric interpretation by adopting multiple sources/voices. Moore also edges close to the contemporary activist poem in the second part of “An Octopus,” in which she offers social criticism of the state of affairs of human relationships versus direct experience with nature. Through her poem, Moore advocates for this poetry of direct experience. There are parallels to this approach in contemporary activist poetry. Contemporary poets have adopted many similar strategies in opening readers’ eyes to a host of contemporary social issues, arguing for poetry that moves out from behind the computer screen into the street. One hundred years later it would be hard to find a stronger poem of witness than “An Octopus.”

Sources:

Leavell, Linda. Holding on Upside Down; The Life and Work of Marianne Moore. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Print.

Leopold, Aldo. “Thinking Like a Mountain.” A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989: 129-133. Print.

Moore, Marianne. “An Octopus.” The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry. Ramazani, Jahan, ed. New York: Norton, 2003: 441-446.

Willis, Patricia. Marianne Moore: Vision into Verse. Philadelphia: The Rosenbach Museum & Library, 1987.

Willis, Patricia. “The Road to Paradise: First Notes on Marianne Moore’s ‘An Octopus.’” Twentieth Century Literature. Vol. 30 No. 2/3, 1984: 242-266. Digital file.