The Territories of Our Spirit

by Mark Tardi | Contributing Writer

The High Alive: An Epic Hoodoo Diptych

by Carlos Sirah

The 3rd Thing Press, 2020

Robert Duncan, the renowned poet of the San Francisco Renaissance, once wrote, “Go write yourself a book and put therein what might define a world.” In his ingenious, genre-busting debut The High Alive: An Epic Hoodoo Diptych, Carlos Sirah lays down his marker and doubles-up Duncan with two books in one, totaling nearly 380 pages and published tête-bêche. One part of his diptych is called “The Light Body,” while the other is “The Utterances.” The reader can begin with either, but I happened to let alphabetical order guide my experience and began with “The Light Body.”

It’s difficult for me to overstate just how audacious Sirah’s work is. Is the writing performance? Open-field dialectics? (Visual) poetry? Radical theatre? Yes—and more. Those familiar with writers such as Thalia Field, Wilson Harris, Edmond Jabès, Nathaniel Mackey, and Toni Morrison will recognize shards or traces in Sirah, but at no point would Sirah’s work ever be confused for theirs. To the extent that this dynamic writing can be glossed, “The Light Body” orbits around two lovers, Noah and Micah, in the aftermath of Noah’s military service—an experience that has cost Noah his leg and much more. The polarity and volley between the two characters is organized in alternating sections which reflect transitions without strict linearity or temporality: Spring and Autumn. As his beloved retreats deeper and deeper within himself, Micah is relegated to a sort of limbo, at times neither included in nor informed of the (literal or metaphorical) journey that Noah is on, yet Micah still does everything he can to salvage the unraveling relationship. At one point, Micah wryly observes, “Mane, I swear ’fore God, Noah / if you didn’t talk in your sleep / I wouldn’t know shit.” (And as both the vernacular and enjambments of these line breaks illustrate—formal elements alive in both texts of the book—Sirah is minutely attuned to the lyric hum and utilizes this to great affect.)

While much of “The Light Body” can be read as a play script, Sirah deftly deploys innovative layout and various interpolations that add palimpsestic emotional layers and continually blur the lines between stage direction, description, and speech act. The narrative also includes blackened shards with white typeface that cut into the text, which could function as directorial notes, an omniscient observer, a Greek chorus, voice of God, or disembodied interior monologue. For me, these interpolations, rather than pulling me out of the narrative of Noah and Micah, served more like doorways that descended into new interiors within the entangled history of their relationship. To this, Sirah also adds images and photographs—of, for example, an African dagger, a beetle, an old bottle, a lariat, and parts of legs floating in space—which can visualize some details between the lovers, add historical weight, or inject fresh considerations to their relationship.

It’s a testament to Sirah’s gifts as a writer that in “The Light Body,” Noah’s trauma inhabits a kind of quantum emotional scale. The formal mechanisms of the work are elucidating, robust, and at times heartbreaking, but for as much as “The Light Body” is performative, the emotional interiority—and the vulnerability revealed—is akin to a fractal or vicious infinite regress. The layers and folds proliferate within Noah’s ongoing implosion. In one of the most gut-wrenching moments between the lovers, Sirah writes:

In the dark

Micah bends before Noah’s

sleeping body.

Micah places a glass on

his chest.

Micah listens

to Noah’s inside.

In the book, this short description is given the entirety of the page, surrounded by empty space, which reinforces the isolation and the naked intimacy of such a desperate—and perhaps innocently child-like—act of love by Micah. For his part, Noah regards his lost limb and wonders if “[m]aybe the hole started from the inside.” This “hole” may be the same place within Noah that feeds his dreams of strangling his beloved or shooting salivating dogs—these worlds within worlds, marred and marked by profound violence.

When Walter Benjamin wrote about the auratic quality of the human in theatre in his “Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” he may not have been imagining reproductions of handwritten epistles, but this is another element in Sirah’s seemingly inexhaustible toolkit: letters. The letters that Micah and Noah leave for each other give voice to what may be sensed but unsaid (for both character and reader). Upon reaching the heart-rending conclusion of “The Light Body,” the reader reaches the middle of the book which instructs “End”—and after turning the book 180 degrees—“Begin Again.” In doing so, you’ll find the other part of the diptych, “The Utterances.” If “The Light Body” expands inwardly and outwardly around an intimate pair, “The Utterances” offers a larger ensemble: a post apocalyptic world peopled with tinges of Samuel Beckett (with figures such as Rebl and Naif being more discomfiting versions of Beckett’s Vladmir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot) or Eugène Ionesco’s The Chairs; but it is absent of the absurdity.

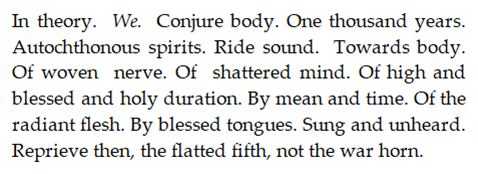

“The Utterances” advances through a series of nights in a city of the future devastated by “The War That Settled Dust”—a city mapped more by ruins and strewn bodies than any architectural grandeur or bustling populations. The locations and characters shift, though there are often pairs: Noe and Wat; Mutta and Chile; Make and Kees; Gucci and Loofah; along with the recurring Theory of Bessie, which perhaps functions as a counterpoint or chorus that signals the contrast between the bodies of the characters and the disembodied consciousness that envelops and weighs in on the events that transpire. The locations are familiar placeholders—city, church, factory, bunker, or bridge, to name a few—but the language that circulates between the characters takes primacy. In many respects, the opening paragraph of the “The Utterances” could be an epigraph for the entire project:

The survivors of “The War that Settled Dust” spend their time creating makeshift families and clinging to whatever tenuous remnants of connection are left. They even seek out (or avoid) “bodies,” which are never referred to as people or humans in the narrative, an act of both sustenance and suspicion. Just as Nathaniel Mackey has imagined the ancient Andoumboulou as analogous to our present condition, humanity as a constant work-in-progress, so Sirah’s inhabitants could be a flashed-forward version of a terrifyingly future-ready humanity that “[tears] skin off cities.” When Naif pays a visit to a character known only as the “Bone Grinder” (possibly a nod to Wilson Harris’s work) to barter a sack full of collected bones, Naif finds him reciting a sort of grotesque mantra—“I smell the flesh. I singe the flesh. / I break the bone. I make the bread.” He wonders if the Bone Grinder ever thinks about the material that gives him his job, to which the Bone Grinder retorts, “I know it’s best not to say that we all know.”

Indeed, “The War that Settled Dust” could perhaps be a reference to Oliver Pitcher’s debut collection, The Dust of Silence; or it could be a reconfiguring of Edmond Jabès’s notion of the book of the Book, the constancy of war coupled with the entire history of human existence; or maybe it’s Sirah’s reimagining of the War to End All Wars. In any case, within the shards of a city, Sirah’s characters eke out their existence and desperately try to stake out some meagre claim on familiarity, even if that involves admonishing others for not attending to responsibilities: “You weren’t looking out. / You were just looking.”—Noe proclaims in chastising Wat.

In the book’s acknowledgments, Sirah credits Zora Neale Hurston’s Characteristics of Negro Expression as having had a direct influence on his writing of “The Utterances.” Having read both, Sirah’s declaration strikes me as more akin to composers creating entirely new compositions based off of the variation of an earlier theme or poets starting a poem with a line taken from another poet. Perhaps Hurston’s anthropological observations presented Sirah with a rich vein to mine, but everything that’s grown around and above that is very much his. Although both narratives point towards theatricality and play scripts, Sirah is guided less by any conventions of playwriting and more by the creative contingencies of the worlds he creates. What could be read as stage directions are never simply that. In “The Utterances,” Sirah inventively uses the term STUTTER to serve the function of stage direction, but it’s both a theatrical beat as well a textual embodiment of one kind of utterance.

Taken together within this astounding book, “The Light Body” and “The Utterances” create a lemniscate that braids the individual to the ensemble; the particular to the plural; to the experience of Black Americans with myriad forms of love, loss, and violence that demand rereading, reconsidering, and re-enacting. But even that description covers only a sliver of what the book actually contains. Corporeality may be a buzzword these days, but Sirah’s work explores the body— and language as bodily—with a care and incisiveness beyond comparison. As a reading experience, at times I needed to pause—to stutter—and reflect on just how much Sirah managed to embed within what can often appear to be spare dialogues or difficult-to-define segments of text; a space where the imperative is to “Shelter your tremble,” and perhaps listening is its own religion. As Ages poignantly reminds us in “The Utterances”: “If we don’t attend to the territories of our spirit, then who will?” Although the writers I noted previously may serve as aesthetic signposts to contextualize his work, there’s no question that Sirah’s debut belongs in their company. If debuts like Thalia Field’s Point and Line or Nathaniel Mackey’s Eroding Witness cleaved entirely new landscapes within contemporary American literature, Carlos Sirah’s The High Alive is equally as fearless—and devastating.

—

Carlos Sirah is a writer and performer from the Mississippi Delta. His work encounters exile, rupture, displacement, and migration. A 2017-2018 Lambda Literary Fellow, Playwrights Center Core Apprentice, and recent Millay Colony residential fellow, Sirah has performed and developed work with a wide array of place-based, social justice and arts organizations across the country from New York to Virginia to Arkansas to California. He is a facilitator with Warrior Writers, a community of veterans who make art. Sirah received his MFA from Brown University in 2017.

Mark Tardi is a writer, translator, and lecturer on faculty at the University of Łódź. He is a recipient of a 2022 NEA Fellowship in Translation and the author of three books, most recently, The Circus of Trust (Dalkey Archive, 2017). Recent work and translations have appeared in Lunch Ticket, The Scores, Denver Quarterly, The Millions, Circumference, La Piccioletta Barca, Jet Fuel Review, Berlin Quarterly, and in Italian translation, Rossocorpolingua. His translations of The Squatters’ Gift by Robert Rybicki (Dalkey Archive) and Faith in Strangers by Katarzyna Szaulińska (Toad Press/Veliz Books) were published in 2021.