The Space Between

by Sarah Bitter | Contributing Writer

Shimmer

Mark Irwin

Anhinga Press, January 2020

In Shimmer, Mark Irwin engages the Latin origins of the verb “responsible”: answered, offered in response, and the poems within the collection produce a deeply serious offering. The first poem begins:

What a great responsibility

to think of things that no longer exist—the tree house

with ladder struck by lightning.The skyscraper whose floors and ceilings collapsed as people dined above

while below computer terminals and desks flew out the windows.What a great responsibility to think of creatures no longer here.

The Tasmanian tiger hunted to extinction, or the golden toad that burrowed . . .

Along this litany of losses, we enter the work of a poet driven by “a great responsibility to give human form to words, to place safety cones / around parts of speech, especially nouns and verbs in the past / whose work will never cease.”

Shimmer’s 68 pages are part elegy for Irwin’s mother (to whom the book is dedicated) and part elegy for a cast of friends, lovers, and children. In Irwin’s words his poems are “this ledge of paper, over / which I lean, trying to touch those I love.” However, Irwin also looks not only back through time, but at our time, the poems gradually forming an urgent consideration of environmental catastrophe, technology, digital living, and human violence.

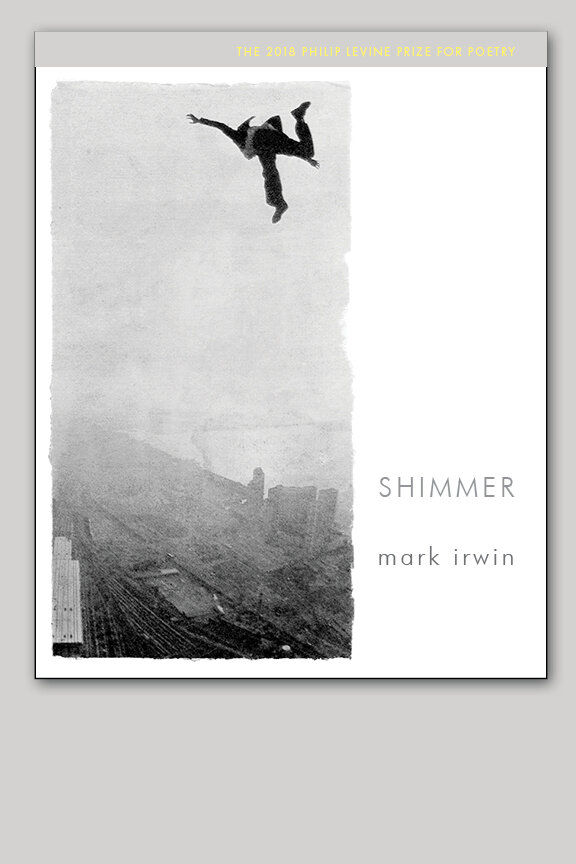

The breathtaking cover image of a man in a suit falling towards a city—Sarah Charlesworth’s “Dar Robinson, Toronto”—places us in the dual position of the witness and the dying at the moment of death. “Dar Robinson, Toronto” appropriates a portion of Andy Warhol’s 1962 silkscreen “Suicide,” which in turn appropriates an unattributed news photo, appropriations which together suggest an endless series of plunging bodies. Thus, the cover art, as it recursively captures the moment of falling, echoes how Irwin’s book seems to be, in part, about the way we are all plummeting towards death in infinite succession. Shimmer’s greatest achievement is, perhaps, the way it considers both how it feels to be plummeting what it feels like to see and know the fallen and falling.

With quiet intimacy, layers of associative meanings reveal and shift as the book’s four sections engage and reengage with the scale of experience, the physicality of life and death, and the nature of memory. Often, reading Shimmer feels like seeing through a lens switching between wide angle and near focus. For example, in the poem “And,” Irwin writes “all the buildings and skyscrapers / turned to rock, and all the rocks to sand while the tiny epic of all / this is being written in red within the four chambers of a sparrow’s heart.” Across its pages, Shimmer also considers not just memory, but its repository, the fragile, fallible mind, especially as it experiences memory loss. Early in the book, Irwin writes, “And the world became one / without names but memory flowed through it like a river.” Later, in the devastating “Two Panels,” Irwin writes of his mother, no longer able to speak or read, passing pieces of color to convey meaning:

When she could no longer speak. When

we passed words on paper, back and forth. When the words meant

nothing. When we passed colors. When red. When blue. When

memory dances till no becomes yes. When

I sing of you. When green.

Poets often pay close attention to color, but in Shimmer color accumulates and suggests meaning in very interesting ways. Sometimes the colors’ meanings seem decipherable, as in Irwin’s “In Autumn” where he writes: “I always feel I’m writing in red pencil on a piece / of paper growing in thickness the way a pumpkin does, / traveling at fantastic speed toward orange, toward rot.” But in other poems the meanings of color seem less legible, as in “Domain,” where Irwin writes: “this green is planning something big, something red.” This abstraction allows the reader room to inhabit the poems, almost as in “Memory” the mother and son passing colors both distances and universalizes; we can only intuit the symbolic order between mother and son without being able to inhabit it. The creation as a reader of an intuited symbolic order for recurring words like snow, red, and green is one of the book’s deep pleasures.

Irwin’s work also considers humanity’s impact on the planet and technology’s impact on humanity. In the sonnet-like title poem, “Shimmer,” Irwin shows humans dehumanized by their spaces, “A high-rise lobby mirror is lobbing / suited bodies back and forth,” and then gestures towards how technology further distances us from human and ecological disasters: “Watch this in your room / along with the Ilulissat Glacier melting, the portable / become monstrous illusion.” Also interesting is “Procession and Zigzag,” in which Irwin writes of “uploading minutes, hours emblazing // the nights, debriding them.” With this technical-medical language, Irwin jostles readers, or at least jostled me, into reconsidering the human-technology-nature relationship. Irwin also makes rhetorical moves that jostle us from the position of witness to implicated. The fascinating poem “Domain” moves from the singular voice of the poet to the collective voice in a moment that strikes me as a deep metaphor for our headlong and determined destruction via overconsumption:

inside each TV a primal fire is burning, and I can feel it,

walking down the street, looking into each of the picture windows.

I’m entering that one’s house now, where the dinner guests are no longer

at their seats but under the dark table, the young and old blowing

out candles, and now we’re taking big spoonfuls, handfuls of burnt

sugar and flour, and with eyes closed, thrust them into each other’s mouth.

Shimmer features a range of image and sonically rich, formally diverse poems; among them, a longer poem called “Dear Red” contains a line that to me summarizes the desire the book the book is responding to: “Between what I see and what I’m unable to say is what / I want to write, and to write it so you will believe.” Here is the poem’s beginning:

Dear Red,

as a rose refolding towards evening. Time,

like a whistle or rust gathering

on the body. Timelike taffy, the kids pulling it now

from their mouths, its pink and yellow

string one may hold decades later as stone.

As we read Shimmer, we’re given strings to pull and stones to hold and turn over in our minds. For me, the great offering of Shimmer is moments when, my mind shifted slightly by Irwin’s poems, I feel the space between what I can see and what I am able to say fill slightly with words.

—

Sarah Bitter is a poet, essayist, and MFA student at the University of Washington.