The Reaching That Makes of Falling Flight

by Darius Atefat-Peckham | Contributing Writer

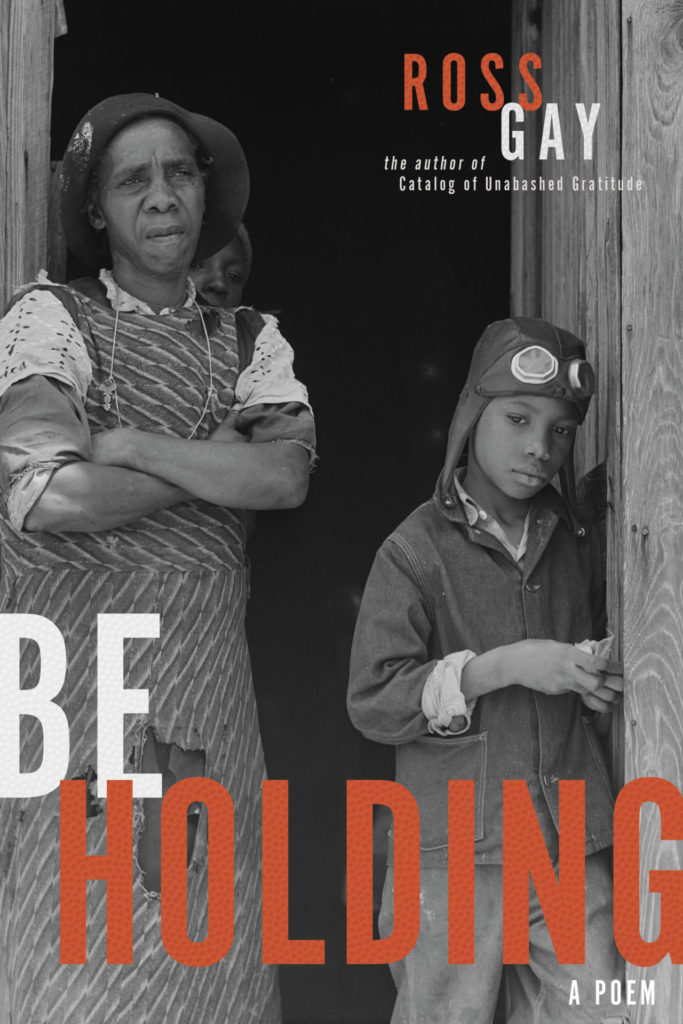

Be Holding

Ross Gay

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020

When I summon Ross Gay to mind—as I often do when I’m writing a poem, parsing griefs, or just struggling, broadly, with the intolerable—he’s likely to appear in my imagination beneath a fig tree on a warm afternoon, sitting in a little corner of his garden and taking notes on the subtle landing of a butterfly against a petal, the way a flower turns its head, eyes scanning what he calls, in his Book of Delights, the “wilderness” of life, where he can set his roots and connect. Over the past few years, Ross Gay has established himself in the literary community as the poet laureate of delight with his Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, a collection of poems which won the Kingsley Tufts Award in 2016, and his Book of Delights, a bestselling book of short essays which came out in 2019. Both collections are similar in their objectives: to reach toward love, or at least try to, no matter the circumstances of the day. It seems obvious, simple, and rewarding work: a poet setting out to write what sparks delight inside himself and why.

Gay’s most recent publication, a book-length poem called Be Holding, released from the University of Pittsburgh Press amid the painful social reckoning, tumult, and grief of 2020, marks a departure from what readers might perceive as Ross Gay’s program of joy. To paint Ross Gay as a poet who seeks to reveal only moments of felt joy would be to misjudge and misunderstand his work. Against that perception he offers what he calls a “false etymology” in order to define his practice as not only the writing of happiness or pleasure-seeking, but as the practice of writing toward, as he says, “de-light . . . both ‘of light’ and ‘without light.’ And both of them concurrently . . .Being of and without at once.”

This is an important distinction to make when reading Be Holding. Ross Gay is a man of mixed race living in America who, having experienced the enormity of both personal and societal grief, does not shy away from historic sorrow. Through associative leaps large and small, Gay reminds us that the history of a moment is wide-ranging and deep. In Be Holding, he transports us, for instance, from the horrors of the Middle Passage to a photograph taken in 1975 by a white photojournalist named Stanley Forman. The photograph, called The Fire Escape Collapse, shows a nineteen-year-old Black woman named Diana Bryant falling with her two-year-old goddaughter from a collapsed fire escape on a burning apartment building, “fixed / falling to [their] death.” Gay leaps as well—from their fall to the Black visionaries he idolized in his youth: Stevie Wonder, Julius Erving, his own father. In making these leaps, he enacts a heritage laced with both Black grief and Black triumph. That spectrum of feeling manifests as he practices his beholding.

In Be Holding the present moment is charged with the weight of history. The poet watches a clip of Julius Erving—Dr. J—making an improbable reverse layup in the 1980 NBA playoffs, “studying forever each minute nuance / of this black person in flight.” It’s late: that time of night when our consciousness slips, when our thoughts are more likely to succumb to anxiety, regret, resentment, unhappiness, and—most dangerously—uncertainty. As the poet moves into a digression about his neighborhood in his youth, he narrows in on a boy napping precariously on a ledge, the traffic humming below him. In that moment, we feel an uncertainty emerge in the voice of the poet, one that Gay presents as almost sinister:

and do you know while composing this

I almost dreamed doom

upon that child

dozing beautifully in my poem

dreaming now above this flying—

This leads us to Gay’s driving question, something he states repeatedly with essayistic concern:

what am I

looking at

what am I

practicing . . .

. . . a mouth perched somewhere between

you better not and isn’t this lovely

Gay aligns himself with the boy napping precariously on the ledge and at the same time with a pedestrian walking below who looks up with momentary concern—and then delight. By demonstrating the ambivalence of his human observer, Gay introduces doubt to the joy so intrinsic to his poetic practice.

Through movements of falling and flight in this book, Gay positions himself in the wake of Black suffering, reminding the reader of those who were “thrown overboard // for the insurance” as well as the ways in which Gay himself contributes to the Black pool of genius—or the “black pull of genius / as in the black tether of genius”—what he also calls “the museum // of black pain.” Gay devotes a large portion of his acknowledgments to Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, and, if read alongside one another, the two texts form a conversation. Sharpe writes about the complexity of what she calls “wake work”a category Be Holding certainly belongs to:

If . . . we think the metaphor of the wake in the entirety of its meanings (the keeping watch with the dead, the path of a ship, a consequence of something, in the line of flight and/or sight, awakening, and consciousness) and we join the wake with work in order that we might make the wake and wake work our analytic, we might continue to imagine new ways to live in the wake of slavery, in slavery’s afterlives, to survive (and more) the afterlife of property.

By offering these different meanings of “wake,” and what Black artists do in the wake to “survive (and more),” Sharpe acknowledges the joy expressed by contemporary Black art as well as the horrors which contextualize its existence. “We gather,” Ross Gay writes, “in the wake of the garden / this looking makes.” The reader is thrust into the peculiar and complicated position of the beholder, both alongside and opposite Ross Gay (and every other player in his poem), who is also the beholder—and, in the “line of flight and/or sight”—the beheld.

In Be Holding, Gay explores the implications of art-making and image-capturing by including the photographs that haunt and contextualize the text. In this way, we too become the beholders, the admirers, of Dr. J’s flight—and are also subject to the slow tension of his falling. When Ross Gay describes The Fire Escape Collapse, he shows Diana Bryant and her goddaughter “held like that / unlovingly by the camera.” By doing that, he demonstrates his own uncertainty and self-implication—and evokes it in us as well.

How do we be

be holding each other

so broken are we by

the breaking and the looking

What is the difference here between the camera lens and the poet’s gaze? What is the poet’s practice? Likewise, Christina Sharpe asks, “What does it mean to defend the dead? To tend to the Black dead and dying . . . always living in the push toward our death?” It could be said that Ross Gay revises and reclaims The Fire Escape Collapse photograph. Sharpe offers that “while the wake produces Black death and trauma . . . we, Black people everywhere and anywhere we are, still produce in, into, and through the wake an insistence on existing: we insist Black being into the wake.” To return to the point of reckoning can exhibit a tender kind of care, the reaching toward love that Gay talks about; Gay’s leap from Dr. J’s triumph to The Fire Escape Collapse isn’t only a contextualization of the happening moment, but a necessary move in order to understand his own wonder, his own joy.

If, in the section about The Fire Escape Collapse, Ross Gay’s attention is trained on the phenomenon of falling, elsewhere it attends the concept of flight. There, Gay directs us to another photograph, this one of a young boy with aviator goggles pushed up onto his brow. The boy in the photograph seems defiant of the frame, as if it were itself a branch from which he could, at any moment, take flight. Gay writes,

he knows

he’s being shot,

he’s being shared,

by someone who doesn’t love him,

Gay makes it clear that flight is an inherent aspect of the boy’s nature, and also of his own nature, the poet’s, who is projecting his own idea of flight onto the boy. Gay writes,

the little galaxies of light lustering

his beautiful brown skin,

his lower lip and nose,

if we bring him so close to us,

we can hear him breathing,

the soft eddying of wind into his nose,

and closer still,until his lungs become kites,

Gay doesn’t mean to transform the human child into the stuff of flight, but rather suggests that the stuff of flight is already there.

If Gay positions himself in the wake, and we consider Be Holding a wake work, he also positions the ideas in the text—and those people held within it—as eddies, a word that pops up frequently throughout the course of the book, and whose definition—“a current of water or air running contrary to the main current”—presents us with interesting associations. An eddy is both the stuff of water and current, of air and breath, and it marries Sharpe’s ideas about a wake to Gay’s notion of flight. At the end of the book, Gay dives back into a memory of playing with his father in the sea:

he said

big breath

and clinging

to his slick manatee

shoulders we plunged

airborne . . .

. . . bodies bursting

as he reached

through the water,

. . . to keep from sailing off,

how many million eyes in the wake

flashing their light at us

clinging to one another

lit by their looking

Reaching toward love can often feel like an impossible practice as we peer into the darkness, the wake, of a moment. Ross Gay persistently reaches toward the love within sorrow, toward hope in the context of grief. Gay writes of his father,

. . . he’d be holding us,

and in this way

flew some from the overboard,

and likewise showed us

how to fly some from the overboard,

by reaching toward

what you love,

which is not a citizenship

we talking about,

but a practice,

despite the hold,

a practice that spites the hold.

Gay allows space for the eddies that run contrary to the current, that spite the hold, that attest to the multiplicities of being that make us human. Be Holding, much like Dr. J’s leap, is a kind of flight in itself, a triumph of tender care and acknowledgement. A breath. Another painfully gorgeous flower in Ross Gay’s garden, almost too lovely to behold.

—

Darius Atefat-Peckham is an Iranian-American poet and essayist. His work has appeared in Indiana Review, Barrow Street, Michigan Quarterly Review, Texas Review, Zone 3, The Florida Review, Brevity, Crab Orchard Review, and elsewhere. He is the author of the chapbook How Many Love Poems, forthcoming from Seven Kitchens Press. In 2018, Atefat-Peckham was selected by the Library of Congress as a National Student Poet. His work has recently appeared in the anthology My Shadow is My Skin: Voices from the Iranian Diaspora (University of Texas Press). Atefat-Peckham lives in Huntington, West Virginia and currently studies Creative Writing at Harvard College.

Ross Gay is the author of Be Holding (2020); Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude (2015), winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award and a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Books Critics Circle Award; Bringing the Shovel Down (2011); and Against Which (2006). He has also published an essay collection, The Book of Delights (2019). Gay is the co-author, with Aimee Nezhukumatathil, of the chapbook Lace and Pyrite: Letters from Two Gardens (2014), and with Richard Wehrenberg, Jr., River (2014). His honors include fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, Cave Canem, and the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference.

He is an editor with the chapbook presses Q Avenue and Ledge Mule Press and is a founding editor, with Karissa Chen and Patrick Rosal, of the online sports magazine Some Call it Ballin’. He teaches at Indiana University and in Drew University’s low-residency MFA program.