The Piecewise Way We Remember

by Brandon Rushton | Contributing Writer

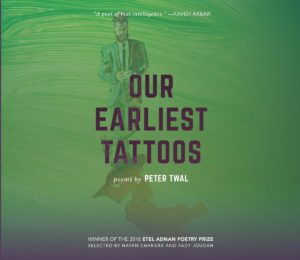

Our Earliest Tattoos

Peter Twal

University of Arkansas Press, 2018

On November 26, 2018, as NASA’s mission control slapped hands in celebration of InSight’s successful landing, its predecessor, Curiosity, was playing a roll as the centerpiece in Peter Twal’s debut poetry collection, Our Earliest Tattoos. The book is a multifaceted experiment that interrogates the poem’s modern and historical role as dispatch and transmission. With a cyborgian intellect, Twal’s speaker constructs a science-scape, a mechanical universe composed of earthly and otherworldly elements. While Curiosity roams the surface of Mars, Twal’s speaker is busy back on earth assembling and disassembling his friends, those patchwork people composed from parts and memories. Through the metaphor of the Mars rover, readers quickly link its prodding of the planet with Twal’s probing of the past. They’re both sifting through the dust and remnants of another time, another world, another planet. They’re looking for signs of life in hopes to prove that—at one time—they were there.

Twal’s speaker insinuates that what appears arid never is. As he interrogates the past, readers come to realize the re-livable aspects of places, people, and time. The past is alive in Our Earliest Tattoos; it’s a reservoir for recollection, a source from which to pull in order to compose a future. The present age, one similar to ours, is a dangerous world of proliferation, a digital maelstrom where dispatches are obfuscated by distraction. The best minds of Twal’s generation are endangered by technology, its proclivity for numbness and lack of action. As initiative is neutralized by its encroachment, the could- be-prophets around him sit plucking the petals from the flowers of instant fame:

. . . My whole generation combing

A hand through its hair Notice me Notice me

not

In the echo chamber of our narcissistic era, clarity is a limited resource, a product of bygone days; days where true language was not drowned out by the static of the self-concerned. When the speaker turns to rely on language, he finds his own words deflected back at him, as he does in the poem “If You’re Worried About the Weather,” where he “cant hear anything / outside of [his] own voice [his] own voiceless.” Twal reclaims new media from mindlessness and resituates tweets, status updates, emails, and text messages as the new artifacts of historical and cultural memory. Twal’s debut is part poetry, part digital anthropology; readers often find his speaker scrutinizing fragments of sentences, bodies, and demolished landscapes. The brilliance of this debut rests in the assemblage of those parts. While disorder is the mainstay medium, there is, paradoxically, something secure and comforting in the vortex: The laws he creates in his poems govern the chaos. For all of the explosive language and content they contain, the poems act primarily as binding agents, giving form to all the attention-deficient flotsam spiraling around us. As the curious periscope of this book swivels to confront the possibilities of past and future, the poems dispatch through time, both ways.

Twal explores that idea of chaotic order all around us. By explosively deconstructing and reinventing the sonnet, he has chosen the form through which he will examine fragments of modern life. Each title has, in some way, been taken from lyrics of LCD Soundsystem’s song, “All My Friends.” Through the electronic fuzz of T.V. static, PA feedback, phonograph scratches, and radio dials, Twal twists together an intimate portrait of family, culture, memory, and loss. Like any good scientist, Twal understands successful experiments are also exercises in constraint (“Even the dumbest explosion / possesses the smarts to say I will only blow up this far”). This scientific awareness and careful approach to experimentation draws Hayan Charara and Fady Joudah to the claim in the book’s introduction that Twal has “succeeded in reinvigorating the form, but also in adding his voice” and that he is a poet “to whose sonnet-conversation we should care to listen.”

In addition to reclaiming the sonnet form from the past, Twal draws inspiration from the mother of experimentation herself. Taking a page from Mary Shelley (“that I could resurrect anything”), Twal’s speaker Frankensteins his friends together through the remnants of an industrial era: “cellophane skin,” “aluminum neck,” and “rusty veins.” His industrial-human-hybrids bring us closer to an old understanding about memory and language: They work together simultaneously to reanimate.

The haunting aspects of absence are felt everywhere in the book. Whether it’s presented through the formal gaps in the reinvigorated sonnet form or, through the frustration of trying to assemble a friend from memory, the apertures left by loss are ever-present. Though we see a speaker wrestling with the pain of reanimating those he loves we come to understand that all efforts are better than the opposite: the apathy of “the piecewise way we forget / people cutting them up, hiding the memories in our freezers.” For Twal, memory is a unit of measurement, a way to keep the scientific mind on its toes, ensuring that it remains inquisitive, calling for new ways to see. He makes that sentiment clear in his poem, “Sewn into Submission”:

. . . Growth would be me

Not expecting you to show up with your shadow unbuttoned

& I stare & those nightmares slowly running progress

are misery, are memory sewing my eyes open

Twal’s book charts a spectrum of absence for its readers, zeroing in on the psychological impacts of sudden loss. Considering the ubiquitous reference to explosives and explosions (IEDs, landmines, etc.) readers get a sense of how complicated it is to cope and mourn the unanticipated. After such an explosion forms an aperture, Twal asserts that what is left—when there is nothing left—is memory. More than that, he pairs his ubiquity of explosives to the torturous practice of waterboarding. This allows readers to understand the larger commentary he has intertwined about diaspora, familial responsibility, cultural lineage, and one’s heritage to a homeland in a region destabilized by the West’s imperialist politics and love of war .

The speaker in this book is accounting for both personal loss and cultural endangerment. No where is this more apparent than in “We Set Controls for the Heart,” where he becomes “this / body of refugees between whose cushions / will you one day find my body.” Twal wrestles with the guilt for not living the same experience of his betters, his ancestors; guilt for the absence of friends, family, and his distance from a history, culture, country, and life; and lastly, guilt for his presence in the face of all that absence. In turn, readers develop guilt for participating in and perpetuating a system responsible for creating the absences the speaker traces and outlines. One of the most moving moments of the collection is when the speaker forges a covenant with his predecessors in the poem “Oh, This Could be the Last Time so Here.” By using toy soldiers as metaphor and medium, the speaker promises to keep the memory of his betters alive, to keep looking for the fragments of their stories everywhere and in everything he does:

. . . Elsewhere, a child loses a few toy

soldiers in a red field: One, prone, wielding a bayonet, while another will never stop

sweeping its metal detector over the dirt

While Twal’s speaker sweeps over the landscape of his past, readers are reminded that memory has reverberations—qualities that sometimes manifest themselves as blowback. Scouring the past can become a form of self-sabotage, a risk Twal’s speaker is always willing to take. The potential reward of successful reanimation is too high: His loved ones might live again. That’s why the speaker doesn’t flinch while addressing those loved ones in the poem “Where Are Your Friends Tonight,” telling them directly that “the doctor / removes shards of you from my skin like splinters.”

While it wrestles with the heaviness of history, Twal’s book is also a statement about being young in the present. The experimentation, energy, and momentum generated in the book could have only been done so by a poet at their beginning. This is a book written in love by a poet ready to prank and play with language, whose irreverent enjambments (“Is the toilet overflowing / Is someone beating off / the hinges of this stall”) convince readers the speaker has bought into the sentiment of LCD Soundsystem’s youthful thesis when they sing “I wouldn’t trade one stupid decision for another five years of life.”

It is the hope and longing of youth that presents Our Earliest Tattoos as a quest for intimacy, whose want for togetherness is a wish that might solder together past, present, and future. The book’s main question is asked in “The Moral Kicks In:” “Were we ever anything / more than echolocation”? How else do we, the young of the 21st century, form a sense of self beyond taking note of the absences around us?

After rendering a poetic sonar system of his own, it feels appropriate that Twal’s speaker gravitates toward the self-destructive after having engaged in such an extensive charting of absence. In the poem “People Who are Trying to be Polite” readers are left with the image of the speaker offering to share a cigarette with the world. So addicted to such a small show of camaraderie, fellowship, and communion, the speaker is willing “even [to] take the end on fire.”

As the intimate actions in Our Earliest Tattoos blend together risk and excitement, readers come to understand that the potentially self-destructive can provide a path toward progress. For example, considering this scene in “Weather, Then You Picked the Wrong Place to Stay” readers are reminded of the destructive ways in which they too forged their path:

. . . Here we are,

you wrapping a plastic bag around my head my tongue trying

to poke a hole through the past

After having been ushered through what proves to be an emotional ringer, readers find themselves frantically longing for the coping mechanisms of their own youth—maybe a long ride to nowhere with some good friends, the windows down and the radio on. Reader, if you find yourself on the road with an absence of air in your chest and can’t breathe, relax: You’re just one of Twal’s blue jays now “back on the moon, eventually bluer than it was born to be.”

—

Brandon Rushton’s recent poems appear in Pleiades, Denver Quarterly, Bennington Review, Forklift, Ohio, and Passages North. In 2016, he was the winner of the Gulf Coast Prize and the Ninth Letter Award for Poetry. His critical essays and reviews appear in Kenyon Review, Poetry Northwest, and Michigan Quarterly Review. Born and raised in Michigan, he now lives and writes in Charleston, South Carolina and teaches writing at the College of Charleston.