So You Are Here, and There Still

by David Roderick | Contributing Writer

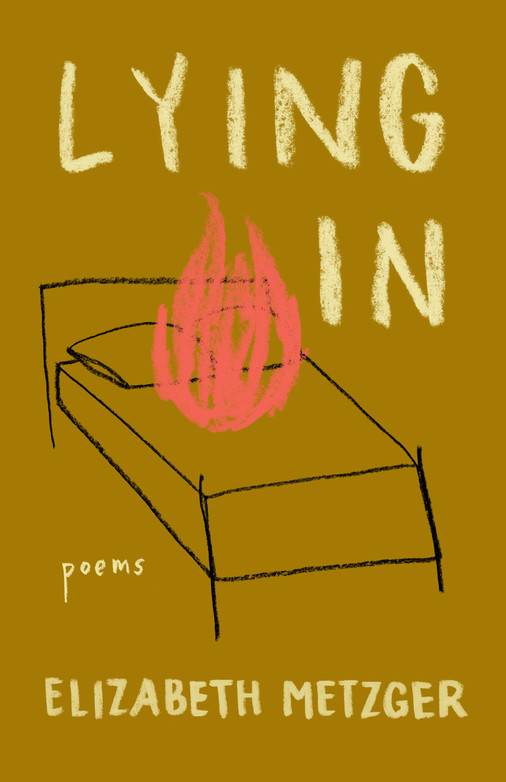

Lying In

by Elizabeth Metzger

Milkweed Editions, 2023

For the title of her new book of poems, Elizabeth Metzger borrows a phrase used to describe the practice of bed rest during or after a mother’s pregnancy. “Lying in” is recommended by an OB-GYN when regular activity could threaten the health of mother or child. Probably for many pregnant women, bed rest is a tedious, restrictive affair. Metzger uses it as a site of creative agency and deep meditation. In fact, I’ve read many contemporary poetry collections inspired by early motherhood and can’t recall one as philosophical as Metzger’s Lying In. While many of her contemporaries build an aesthetics from an occupied self, Metzger seems more interested in erasing individual identities, especially her own. Her poetry is concerned with consciousness, with existence and processes of creation, not how bearing and rearing children harries a lifestyle or puts stress on a profession or marriage.

Lying In opens with the title poem, a sequence occurring in nine meditative episodes that embody the experience of young motherhood when time isn’t linear but rather a dimension in which mother and child sleep, eat, and breathe. The first lines strike a key note: “On bed rest desire becomes a sheet. / Let it fall over me / without hands. Let it.” Metzger’s arresting metaphor (“desire becomes a sheet”) suggests that her speaker lacks agency, that her own desire is now elsewhere, beyond her body—perhaps foreshadowing a sensation she will experience after she gives birth to her child. Her body is a vessel through which experience flows: feelings, images, observations, and memories. I find Metzger’s poetic mode refreshing even though some lines or whole portions are so opaque they thwart my inherent desire for narrative structure or explanation. But Metzger rarely deploys narrative techniques and avoids entirely the notion of motherhood as a social construct. “Forget mothers,” she writes, later in the sequence. Throughout Metzger’s poems, we experience an artist patching together experiences– present and past–, sometimes creating tectonic friction between them, in order to dwell on the meaning of life. In one section the speaker craves sex during pregnancy. In another, she mourns a terminated one. Birth, sex, and death huddle together in these episodes—a condition of lying in. The last lyric meditation leaps ahead a few years, when the speaker can’t resist kissing and tickling her (now) four year old son. Closing out the sequence, Metzger writes,

The world says wean your grief

before it outweighs love.

What if mine does,

what if I put a screen in front

of my boy at noon

to hear myself think.

How should I beg.

What mother.

I lost the baby, I did

even though he lived.

The layers of ambiguity and contradiction in this passage beguile me—especially Metzger’s elliptical transitions and questions delivered as statements. Her koan-like comment at the beginning of the excerpt gives way to a sense of personal failure (the speaker’s own grief threatening to outweigh her love), and yet her answer to this problem is to allow her son to sit in front of a screen so that she can “hear herself think.” One would think the device might further separate the mother from her child, perhaps increasing her grief. Metzger conveys the idea that any true feeling is too nuanced and complex to define in language. All she can do is approach the feeling, or rather allow a feeling’s contours to carry her through time. The boy is lost only in the sense that he has permanently departed the mother’s body and their shared symbiosis.

Metzger often addresses a private “you” in her poems, usually speaking to her children, mother, or husband—an effect that puts the reader in the position of eavesdropper or interloper. One elegy, “The Impossibility of Crows,” addresses Lucy Brock-Broido, a poetry mentor whose aesthetic, especially the notion that “a poem is troubled into its making,” evidently informed Metzger’s work. Several poems in Lying In are written for or about poet Max Ritvo, a close friend who was dying (as Metzger acknowledges in the back of her book) while she was first pregnant. This combination—Ritvo at the threshold of death, Metzger on the verge of giving birth—inspires some of the strongest poems in the book, including “Godface,” which begins:

Once I sat straining to keep you whole

when Max said

look up

that high window was made to keep you aware

of an exit you can’t access

but will be forced through.

You will want the exact pain then

you would die of now.

The first line points again toward the condition of lying in. Ritvo’s ghostly appearance purposefully supports the speaker’s own act of (pro)creation. He’s there to direct Metzger’s attention away from her discomfort and toward larger metaphysical considerations, and, maybe, toward the artistic possibilities of her condition. In the stanza that follows this passage, Ritvo compares the mosaic tiles of a floor to god, “a face designed / with all our dead / in novel arrangements— / friends, ancestors, strangers, / even what has not yet lived.” This is a bold ambition for art—to connect us with the other members of our species, those who have preceded us and those who will follow. It’s also an effective spiritual construct for erasing the speaker’s individual desires. In the third and final stanza, Metzger course-corrects and reframes the poem’s emotional stakes by addressing the child directly again:

So you are here, and there still,

making up my godface,

and if by winter you raise your eyes

into this dimension,

you will already have renamed the places

my body touches

through this one-room world.

Here the speaker and child experience their world intimately but within the context of expansive time, “So you are here, and there still”—physically “here,” I suppose, but simultaneously “there,” lying in with the speaker as she waits and writes and is visited by Ritvo’s spirit. Metzger’s tone is often matter-of-fact, suggesting that we all live in the presence of spirits, we all live in a condition of awe and wonder in which childbirth and death mirror each other. If the poems in Lying In have any wisdom to impart, it’s that our lives are transitional and contradictory, and that the act of creation depends on asking broad questions instead of providing specific answers.

David Roderick is the author of Blue Colonial and The Americans. In Berkeley, California he co-directs Left Margin LIT, a creative writing center and work space for writers.

Elizabeth Metzger is the author of Lying In, as well as The Spirit Papers, winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry, and the chapbook Bed.