Singing the Midwest Electric

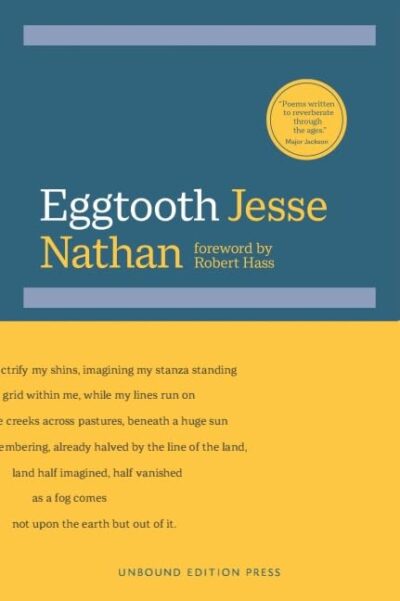

Eggtooth

Jesse Nathan

Unbound Editions Press, 2023

If a good poet is someone who, as Randall Jarrell wrote, “manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms to be struck by lightning five or six times,” then Jesse Nathan needn’t track the clouds much longer. Eggtooth, Nathan’s debut collection, makes the most of its poet’s Kansas adolescence, a childhood spent “pricking on the plaine” (to misuse Edmund Spenser). In “Between States,” a long poem near the book’s climax, Nathan sings the Midwest electric:

[the] stinging nettles in my path

electrifying my shins, imagining my stanza standing

for the grid within me, while my lines run on

like creeks across pastures, beneath a huge sun

of remembering, already halved by the line of the land

His words purr with electric potential; the run of i-sounds in “imagining,” “stinging,” “electrifying,” “standing,” “shins,” and “grid” generate both a tactile restlessness and an animate pleasure. The poet is energized by a landscape whose nettles, paths, and waterways he likewise channels, or conducts, into words.

Poem—and poet—as landscape is an old mode in American verse. Walt Whitman’s “American Feuillage,” for instance, exemplifies this mode a rippling, sinuous line:

Encircling all, vast-darting, up and wide, the American Soul, with equal

hemisphere—one love, one Dilation or Pride; . . .

All These States, compact—Every square mile of These States, without excepting a

particle—you also—me also . . .

Singing the song of These, my ever-united lands—my body no more inevitably united,

part to part, and made one identity, any more than my lands are

inevitably united, and made ONE IDENTITY; . . .

Nathan adopts much of Whitman’s verve but struggles with bottom-heavy figurations: “stanza standing” is sibilant mouthwash, and “a huge sun / of remembering” reads almost like received wisdom. Regardless, Nathan’s adaptation of the John Donne stanza—seven or nine lines with the last three shortened or indented—wisely avoids, per Yvor Winters, the “Whitmanian notion that one must write loose and sprawling poetry to ‘express’ the loose and sprawling American continent.”

“The Long Distance” shows off a more local knowledge of American subjects, and not-just-American English:

Sunday, in his grandmother’s time

you went visiting. Noontime news, topped with beet borsht

and pickled pigs’ feet, cottage cheese stuffed in pancakes –

and schputting, silly talk – and coffee.

If the Midwest is, as William Gass wrote, “a dissonance of parts amid a consonance of towns,” then the Midwest’s vague perimeter, south central Kansas, where Nathan grew up and sets his poems, is merely a consonance of parts—of borscht and nalesniki from some ubiquitous Old Country, of likewise ubiquitous coffee and news, of pigs feet and schputting (“bullshitting” from the Pennsylvania Dutch). Then later:

His art,

with his hopes, had conspired to conduct him

many states away, but even now when

Sunday’s here he calls his kin.

“Conspired to conduct” reads self-consciously archaic, ditto call (not visit). There’s something clinical and undomestic about this—serious, chilly, unfamiliar. The words are extenuated and alien, with a thrilling sense of dispossession, of a family not in habitation with itself. In risking infelicity, unease, awkwardness—all things that prey on a poem’s neatness of finish—Nathan opens his poems up to what Robert Lowell called “all that grandeur of imperfection,” allowing himself to partake of a wider chromatic range. Nathan’s gently alliterative “A Country Funeral” possesses a continual imagistic and musical gusto:

The breeze, quick-footed, skims the beards of wheat

trailing its hem over yellowing tassels

with a gliding so cruel for appearing so free

as it blows through a hog-tight bull-strong fascicle

of shelterbelt planted to revoke

its force and flow

This stanza puts on an almost Homeric bearing; its galloping dactyls replicate the drift and stutter of wind on wheat, helping a reader to imagine this landscape and its dry particulars. In “towns called Empire and Cicero” Nathan’s speaker remembers the “Roma [his] grandmother heard // in that pasture as a child, they would canvas the farmhouse / barter for milk.” These lines, in aggregate, disclose surprising cultural proximities and abet a resourceful pun on “Roma” and “canvas”: nomads in canvas houses “canvassing houses.” All this constructs a kind of idea thresher, a jumble of imaginative worlds, with which Nathan compresses American civilization into and with sound. Hence Nathan’s ironic reapplication of Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright”: “Before we were her people. She was ours,” one of that great poet’s faultiest sentiments. Nathan dismisses Frost out of hand as “a poet / having a sit before he blunders on with his eclogue,” and instead imagines, in “What Ruth May Have Wondered,” a terrain indifferent to new, and all, comers:

Silence in the countryside gets so dense and so deep

it amasses body, untellable shape, heavy, larger

in its nothingness. On windless evenings

it would wrap around us like a vast comforter.

Your ears can ring with it,

it seems a witness

listening, swallowing itself.

Nathan’s rhymes are usually muted and unobtrusive, sounds half-remembered or subsumed by their surroundings: “deep” hardly inhabits its match-word “evenings,” and “larger” rhymes with “comforter” by default. “It,” “witness,” and “itself,” all carry the impersonal pronoun “it,” an appositive, here, for silence.

Motivating all of this is the deeply American hope to find oneself in the landscape, to translate observation into self-knowledge. In dramatic terms, self-knowledge means tragedy. But Nathan isn’t a dramatic poet and, for all his I’s, he isn’t a lyric poet either, at least not principally; there’s almost always another person in these poems, and more than a third adopt the first-person plural. So he is, by William Epson’s definition, a pastoral poet in the sense that he’s interested in social occasions and relationships. These poems express a prairie sociality counter to D.H. Lawrence’s only somewhat despairing quip that “one forms not the faintest inward attachment, especially here in America.”

Nathan’s concerns, his language and social landscape, are so external, so wonderfully exposed, that sometimes his expansive method—the urge to get everything into his poems—gets the better of him; there are freights of overwrought lines, broken synecdoche, sad assonance. But more than anything is a faith in logopoeia, Ezra Pound’s sometimes unhelpful but wiser-than-he-knew formula for poetry, “doing things with words.” “Pastoral,” to that end, is pure imagisme, describing a dead fledgling, with an acid-dry last line:

I step in what

seems like a redwing

under the swing.

Ants scramble out

“Archilochus,” on the other hand, begins in the tranquilized delight of the early morning, its contrasting vowels and occasional fricatives smoothed over by l’s, w’s. and m’s:

Woke to a wind that rose full of birdcall

dropping it fresh as if drawn from a well.

Starlings mobbing elms like a creek talking

Farmhouse window ratting lightly.

Nathan’s palpable joy in hitching sounds to unusual partners is intense and refreshing, especially in the service of such landscaped grandeur as invigorates this collection. I’m reminded of Wallace Stevens’ complaint to Frost: “The trouble with you, Robert, is that you write about subjects.” And Frost’s counter: “The trouble with you, Wallace, is that you write about bric-a-brac.” Nathan proves them right in combination. Eggtooth—with its startling range of reference, madcap vocabulary, and alliterative vigor—makes a compelling case: the American subject is bric-a-brac.