This essay is part of a series in which Poetry Northwest partners with Seattle Arts & Lectures to present reflections on visiting writers from the SAL Poetry Series. Alice Notley reads at 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday, April 5 at McCaw Hall. Previous installments include essays on Ross Gay and Lucie Brock-Broido.

“The Great Punctuation: Alice Notley & Mother-Bright-Appearance” by Sierra Nelson

I first encountered Alice Notley’s work seeing her read in Seattle for the Rendezvous Reading Series cosponsored by Subtext. It was 1999. It was at Hugo House, which had just barely hatched. I was in my mid-20’s, not even hatched, in my first larval year of an MFA, second year performing as The Typing Explosion. In fact, it was fellow Typista Rachel Kessler, who was also a co-curator of the Rendezvous Readings, who insisted I go hear Notley. She’s coming from Paris! By way of New York (by way of the so-called second generation of The New York School); by way of Chicago; by way of Needles, California in the Mojave Dessert; by way of Bisbee, Arizona; by way of being born in 1945. “She has never tried to be anything other than a poet, and all her ancillary activities have been directed to that end,” says one bio. Who was she?

I remember that night Alice Notley read like a flume—a torrential, streaming force—almost terrifying yet deeply invigorating, like a dynamic waterfall, or “in a gesture both ecstatic and trembling, like a sudden blaze rushing upward,” to quote Borges quoting pseudo-Dionysus describing the seraphim in A History of Angels.

Seeing her read was a revelation, both for her words and her presence. At that point for me to read my own poems on stage would require much shaking and crying in a bathtub the night before, testing out my poems in barely a whisper. (Which might seems strange as I was performing often as The Typing Explosion then, creating extemporaneous poems in bright costumes before live audiences with my collaborative hive-mind, Sarah Paul Ocampo and Rachel Kessler—but we never had to speak while performing, except through our secret language of bells, horns, and whistles, and the words we typed on the page.) For all I knew Notley might have her own pre-reading anguish too, but that’s not what we saw on stage. I had the distinct impression she wasn’t reading her poems—they were coming through her, oracle through sibyl.

Though it wasn’t just that she was a powerful performer. Hearing her read I knew I wanted to spend more time with her (many) books too. Hearing her words I felt urged to delve deeper into the texts, to have more time to sift through the sibyl’s oak leaves left for us at the mouth of the cave.

Rachel Zucker, in her book MOTHERs, writes:

I am reading Alice Notley. She has done everything already.

and get scared till I am I

scareder and scareder

then calm and enter where oil of I does flow

oleanders ah touch and step up aha oleanders oleanders and

touched they make

me be here in the strange scented present

up and if I enter I have truly to enter

stars weren’t alive before me anyone’s from the most ancient wildness

– Alice Notley

Encountering Notley again in Zucker’s writing confirmed my early impressions, but also revealed to me that what had felt like a private experience was actually shared by the many who also adore Notley’s poems (she’s called “one of the greatest living poets” by the Poetry Foundation, for heaven’s sake!) and what those poems evoke in us. Zucker again: “I promise never to write about how Alice Notley’s poems work. Because what if I kill it—that magic thing that makes me feel, for a moment, that I can do anything?”

I almost don’t want to tell you about Descent of Alette. Maybe you already know. You know. Or maybe you’ve just heard: a feminist epic, each page a poem itself, but it is also a narrative, a hero’s journey through the underworld, an underworld filled with subways. Here’s Notley from a recent interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books:

I wanted to write an epic in which the hero was a woman. The epic was held as the epitome of writing—a hero, a man who changes everything there is by entering into combat with something. The entire history of the epic is that, in every culture. But then I found one that wasn’t like that, the Sumerian Descent of Inanna, in which the hero, Inanna, is purely interested in finding out what death is. It’s an inquisition through experience…. The way it was set up was very dreamlike. She was the hero, and what she wanted was knowledge.

And this from her preface to Homer’s Art, which uses a similar form and catalyst for its epic, regarding the “female narrator/hero”:

Perhaps this time she wouldn’t call herself something like Helen; perhaps instead there might be recovered some sense of what mind was like before Homer, before the world went haywire & women were denied participation in the design and making of it. Perhaps someone might discover that original mind inside herself right now, in these times. Anyone might.

Dreamers dreaming within dreams. An eyeball opens on the subway car floor. A woman who strips until her face, then whole body, becomes a bird. Disembodied voices whisper of revolution, of fathers and mothers. An owl, a “simple owl,” as big as a subway car. A subway car filled with blood. A painter who paints air, and once paints color on a bat’s wing, desperate for a medium that is not controlled by “the tyrant,” the sinister figure who haunts the book’s narrative, because he “owns form.” A giant snake that sleeps in the subterranean shadows but wakes just long enough to whisper to Alette, “‘When I was’ ‘the train’ “When I was’ ‘the train…’.” And this is just in Book One! And that’s not even the wildest part!

Dreamers dreaming within dreams. An eyeball opens on the subway car floor. A woman who strips until her face, then whole body, becomes a bird. Disembodied voices whisper of revolution, of fathers and mothers. An owl, a “simple owl,” as big as a subway car. A subway car filled with blood. A painter who paints air, and once paints color on a bat’s wing, desperate for a medium that is not controlled by “the tyrant,” the sinister figure who haunts the book’s narrative, because he “owns form.” A giant snake that sleeps in the subterranean shadows but wakes just long enough to whisper to Alette, “‘When I was’ ‘the train’ “When I was’ ‘the train…’.” And this is just in Book One! And that’s not even the wildest part!

Here is “Descent from Alette,” a quieter poem from a bit later in the book:

“I walked into” “the forest;” “for the woods were lit” “by yellow

street lamps” “along various” “dirty pathways” “I paused a moment”

“to absorb” “the texture” “of bark & needles” “The wind carried”

“with a pine scent” “the river’s aura—” “delicious air” “Then afigure” “appeared before me—” “a woman” “in a long dress” “standing

featureless” “in a dark space” ” ‘Welcome,’ she said,” “& stepped into”

“the light” “She was dark-haired” “but very pale” “I stared hard at her, realizing” “that her flesh was” “translucent,” “& tremulous,” “awhitish gel” “She was protoplasmic-” “looking—” “But rather beautiful,”

“violet-eyed” ” ‘What is this place?’ ” “I asked her” ” ‘It would be

paradise,’ she said,” ” ‘but, as you see,” “it’s very dark,” “& always

dark” “You will find that” “those who live here” “are changed”“enough” “from creation’s first intent” “as to be deeply” “upset . . . ”

“But you must really” “keep going now’ ” ” ‘Are those tents” “over there?’

I asked” “I saw small pyramids” “at a distance” ” ‘Yes, these woods are”

“full of beings,” “primal beings,” “hard to see—” “because it’s”“always dark here” “Most of them” “need not concern you now” “But

wait here,” “someone is coming” “to show you your way’ ” “She stepped

back into” “the shadows,” “turned & left me”

Each poem in this book is like entering a dream. Not like hearing the story of someone’s dream retold, but the more difficult task, nearly impossible, of what a dream feels like from the inside. Like a dream the poems are luminous and full of portent, even when little is happening overtly, or even when they feel like a nightmare, operating by their own logic.

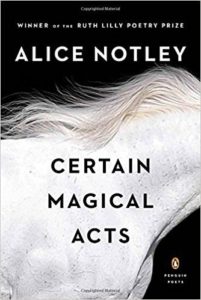

Examples of things I like about dreams: you don’t have to walk a long way to get somewhere; you see people in them you’ve never seen before; there is no closure; poems and songs come to you that you don’t have to take the trouble to write. There is a magic place one can go to to write poems: thus the title of my new book, Certain Magical Acts.

– Alice Notley, from “Dreaming This World Into Existence: An Interview With Alice Notley” by Sarah Gzemski, The University of Arizona Poetry Center

For Notley, dreams are not a separate occurrence from waking life—she sees them as made from the same fabric of experience. In that same interview she says:

A dream is just something else you did; what happened in it is something else that happened…. When I read one of my longer books that contains a lot of dream mixed with material made up on the spot, I can’t always remember which parts I dreamed and which parts I made up. I sometimes suspect we dreamed this world into existence, dream our societies and our lives.

– Alice Notley, from “Dreaming This World Into Existence: An Interview With Alice Notley” by Sarah Gzemski, The University of Arizona Poetry Center

Though she also notes that poetry and dreaming are not synonymous: “Poetry itself is different from dreaming, because it has a more deliberate form and because it has its ravishing sound.”

Which brings us back to form, and how this series of poems build their “ravishing sound,” their particular, peculiar music—and the question I have been dancing around: what is happening with this punctuation? The whole book of Descent of Alette is written this way. After awhile I stopped noticing it as strange, though it never stopped affecting how I read the poems, even just to myself: slowed down, hesitant, breathless—whispered, channeled, careful—overheard, straining to listen—each moment arriving piece by piece, the journey a deliberate step by step. As if each phrase is arriving to us from over a long distance, via a telegraphic system employed by spirits and ghosts [stop].

This is how Notley herself explains her use of punctuation in her author’s note for Descent of Alette:

A word about the quotation marks. People ask about them, in the beginning; in the process of giving themselves up to reading the poem, they become comfortable with them, without necessarily thinking precisely why they’re there. But they’re there, mostly, to measure the poem. The phrases they enclose are poetic feet. If I had simply left white spaces between the phrases, the phrase would be rushed by the reader—read too fast for my musical intention. The quotation marks make the reader slow down and silently articulate—not slur over mentally—the phrases at the pace, and with the stresses, I intend. They also distance the narrative from myself, the author: I am not Alette. Finally they may remind the reader that each phrase is a thing said by a voice: this is not a thought, or a record of thought-process, this is a story, told.

I believe poetry is language’s most radical possibilities, possibilities which include prose and what prose is capable of expressing, but with the freeing capability of moving beyond limiting grammatical structures and linguistic norms as needed. Yet it is rare that a poet helps us feel poetry’s radiant possibility and potential radicalness while also serving a poem’s images or narrative. Notley recognizes, in a conversation with BOMB Magazine, that potential, and responsibility, of her craft: “It’s a huge job to be a poet. It’s the most essential thing there is….Poetry is the species…emphasize the ‘is.’ That’s who we are, that’s how we see….Prose is very, very flat. But we’re not flat. We’re dense and layered.” I count Notley among the Great Punctuationists, along with Emily Dickinson:

They shut me up in Prose –

As when a little Girl

They put me in the Closet –

Because they liked me “still” –Still! Could themself have peeped –

And seen my Brain – go round –

They might as wise have lodged a Bird

For Treason – in the Pound –Himself has but to will

And easy as a Star

Abolish his Captivity –

And laugh – No more have I –

Eighteen years later, now newly a mother, I am reading Alice Notley, new and again, and discovering something else. Reading Rachel Zucker’s lyrical essay collage MOTHERs—where Zucker writes about her own mother, being a mother and poet herself, as well as about her two chosen mother-mentors, Jorie Graham and Alice Notley—made me see it:

Maybe it’s because all of Alice Notley’s poems seem to have children in them. She is always a mother. Graham, on the other hand, has a pre-mother self or a non-mothering mind she can access.

That had never occurred to me. Reading Notley in my 20’s, I did register in some way that she was a mother: knew that she had been married to fellow poet Ted Berrigan, and that their two sons Anselm and Edmund are both poets in their own rights—and I even remember enjoying in particular the way some of her poems embed conversations with children into their language, and include fragments of child-born linguistic strangenesses in their texture. (“Mommy  what’s this fork doing? / What? / It’s being Donald Duck,” Alice Notley, “January,” Selected Poems of Alice Notley). But the very fact that children are present in the work, that Notley chose to include them and their voices in the poems’ world, and included, too, the shifting and overlapping territories of perspective from being woman-poet-mother-mind—I hadn’t paid attention to that. Because on some level of course these things would be included, in the range of human experiences. But also, it is still a question, posed by society, internalized, the supposed divide: Am I poet? Or a mother? A self? Or a mother? A mind? Or a mother?

what’s this fork doing? / What? / It’s being Donald Duck,” Alice Notley, “January,” Selected Poems of Alice Notley). But the very fact that children are present in the work, that Notley chose to include them and their voices in the poems’ world, and included, too, the shifting and overlapping territories of perspective from being woman-poet-mother-mind—I hadn’t paid attention to that. Because on some level of course these things would be included, in the range of human experiences. But also, it is still a question, posed by society, internalized, the supposed divide: Am I poet? Or a mother? A self? Or a mother? A mind? Or a mother?

From the very first poem in Selected Poems of Alice Notley, “Dear Dark Continent”:

Dear Dark Continent:

The quickening of

the palpable coffin

fear so then the frantic

doing of everything experience is thought ofbut I’ve ostensibly chosen

my, a, family

so early! so early! (as is done always

as it would seem always) I’m a two

now three irrevocably

I’m wife I’m mother I’m

myself and him and I’m myself and him and himBut isn’t it only I in the real

whole long universe? Alone to be

in the whole long universe?But I and this he (and he) makes ghosts of

I and all the hes there would be, won’t be…— Alice Notley, from “Dear Dark Continent”

It must have seemed so integrated into her writing I had not registered it as radical, or unusual, to leave those parts in: the parenting, the interrupting, the strange and vibrant language strings of talking to children, the weirdness of self, un-self, the body, whose body, the pronouns of being someone’s mother.

I’ll look up “love” in the dictionary. They’re beautiful.

Bodily they’re incomprehensible. I can’t tell if they’re

me or not. They think I’m their facility. We’re all about

as comprehensible as the crocuses. In myself I’m like a

color except not in the sense of a particular one. That’s

impossible. That’s under what I keep trying out. With

which I can practically pass for an adult to myself. Some

of it is pretty and useful, like when I say to them

“Now will I take you for a walk in the snow to the store”

and prettily and usefully we go. Mommy, the lovely

creature. You should have seen how I looked last night,

Bob Dylan Bob Creeley Bob Rosenthal Bob on Sesame Street.

Oh I can’t think of any other Bobs right now. garbage.

It perks. Thy tiger, thy night are magnificent…–Alice Notley, from “January,” Selected Poems of Alice Notley

“Are you writing poems about him? About this experience?” people ask me about my baby, about having a baby. I am and am not. Some poems about, some poems diffused, in others (decidedly? “a non-mothering mind”?) not. But also, why not?

As for how raising kids informed my writing, I had been from my time in Chicago the only poet I knew of who used the details of pregnancy and motherhood as a direct, pervading subject in poems, on a daily basis, as if it were true that half the people in the world gave birth to others and everyone had been born. As far as I’m concerned, I’m the first person who ever wrote such poems, and feel as if I could probably document the fact. I was a freak and a pioneer. In New York the kids were a little older and more articulate; they became part of the poems which included my friends and the city.

– Alice Notley, “A Quick Interview with Alice Notley” by Corey Zeller, Ampersand Review

Up at 2:00 a.m., 4:00 a.m., walking with the baby around the kitchen, I can see from our back window cab lights on in some of the trucks parked down by the industrial buildings. Who is up at these odd hours? All the mothers and long-haul truckers. Lonely jobs, in a way, isolating, but also much singing, covering the distance.

Maybe all mothers are faking it, making it, making it up.

…I’m no more your mother

Than the cloud that distills a mirror to reflect its own slow

Effacement at the wind’s hand.All night your moth-breath

Flickers among the flat pink roses. I wake to listen:

A far sea moves in my ear.One cry, and I stumble from bed, cow-heavy and floral

In my Victorian nightgown.

Your mouth opens clean as a cat’s. The window squareWhitens and swallows its dull stars….

– Sylvia Plath, from “Morning Song”

All mothers inventors, inventors of the world.

“…You can’t stop me, I tell the tiny dog trying to be cute. I invented dancing on picnic tables. I invented drinking wine, I invented having babies, I invented wearing housedresses and combat boots. I return to the old tree, more visible in its absence. I go over and sit right on top of one of the smoking 14 year-olds, as if he were not there. I can’t even feel his skinny legs under me. It’s just like any other park bench. I am filled with 1980’s synth bass. I can feel that frisbee on my eye teeth. I put the whole park in my mouth and walk away.”

– Rachel Kessler, from “When We Were the First People on Earth to Give Birth”

Motherhood. The -hood is a state of noun-ness, a position or condition, tracing back to Old English, with cognates –heit (German) and –heid (Dutch), all from Proto-Germanic *haidus, meaning literally “bright appearance,” from PIE “bright, shining.” That –hood was once a free-standing word (see hade), now in Modern English surviving only as a suffix. Like little red riding hood, Motherhood is a mythos, a mantle, something to put on. A bright and shining particle absorbed into another stat—a position, a condition—transforming it.

Poetry does make for change, but it does it by being rather singular. It is involved in the creation of reality out of tiny sounds and meanings, sort of like particle physics but on the creation level. I know this sounds highfallutin, but I believe it.

– Alice Notley, from “Dreaming This World Into Existence: An Interview With Alice Notley” by Sarah Gzemski, The University of Arizona Poetry Center

I can’t wait to see Alice Notley read on April 5th for Seattle Arts & Lectures, discovering (rediscovering) what else I have been missing in Notley, and continuing to be changed by her poetry, by her person, for decades to come.

—

Sierra Nelson is a Seattle-based poet and text-based performance and installation artist. Her books include lyrical choose-your-own-adventure I Take Back the Sponge Cake(Rose Metal Press) made with visual artist Loren Erdrich and forthcoming poetry collection The Lachrymose Report (Poetry NW Editions). She is a MacDowell Colony Fellow, Pushcart Prize nominee, and recipient of the Carolyn Kizer Prize and Seattle Office of Arts & Culture’s CityArtist Grant. Nelson is also co-founder of performance groups the Vis-à-Vis Society (2004-present) and The Typing Explosion (est. 1998). She teaches a variety of places including at Hugo House, through Seattle Arts & Lectures’ Writers in the Schools (WITS) program at Seattle Children’s Hospital and elsewhere, and through University of Washington in Bothell, Friday Harbor, and Rome. For more info: songsforsquid.tumblr.com