Shall We Play a Game?

by Daniel Jenkins | Contributing Writer

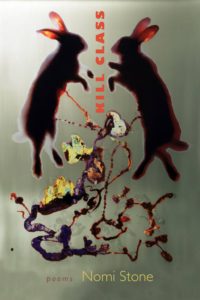

Kill Class

Kill Class

Nomi Stone

Tupelo Press, 2019

I must’ve been eight or nine the first time I watched War Games, the 1983 action film starring Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy, about a tech-savvy teenager who hacks into a computer war game called ‘Global Thermonuclear War.’ Much of the film involves Broderick and Sheedy running into and from the government, but what has stayed for me is the five-word question that flashes across an old black DOS screen, cursor blinking green on black: SHALL WE PLAY A GAME? At the story’s conclusion, when playing ‘Global Thermonuclear War’ is suggested for a last time, the computer says, A STRANGE GAME. THE ONLY WINNING MOVE IS NOT TO PLAY. This blur between playacting and real warfare in the film scared the hell out of me. Those five words became an entrance to my childhood reality: growing up in a culture saturated with an enemy—The Soviet Union—somewhere over “there,” but not “here.” Kids in the 80s could unravel the acronym ICBM. I knew their purpose. But never once was I asked, Shall we play a game?

Kill Class, the second full-length collection of poems from poet and anthropologist Nomi Stone, embodies the fear and reality of this question. In the same way Stone used her fieldwork studying the Jewish community of Djerba in Tunisia through her first poetry collection, Stranger’s Notebook (2008), she opens her field journals once again in an unveiling of the American military machine. Stone explains in the book’s contextual notes that these poems come from

. . . two years (2011-2013) of ethnographic fieldwork, observing predeployment exercises in mock Middle Eastern villages at four military bases across the United States. The setting of these poems is the Middle East-inflected, US military-created fictional country of Pineland, in the woods of the American South, where people of Middle Eastern background are hired to theatricalize war for the training soldiers, repetitively pretending to bargain and mourn and die.

Kill Class gives us Gypsy, the collection’s heroic centerpiece. She is, according to Stone, a hybridized anthropologist-speaker and sometime “role player.” Through her studies of Pineland, she observes, interviews, and even participates in war games along with those people of Middle Eastern background who have been hired to play guerillas, the dead, the grieving, and the avenging. Throughout, Gypsy and the role players receive instructions from American soldiers conducting the trainings. Kill Class ultimately asks readers—through digressions, refractions, and the dismantling of consciousness—to directly confront the indirect and faceless experience of 21st-century warfare.

Sonically, the book maintains a percussive character, beginning with “Human Technology,” and one passage in particular:

I am walking between their blank faces,

their bullets traveling at the speed of sound. One soldier

who roasted a pig on his porch barbecuing until sinews were tendertells me he waited above the Euphrates and if they tried to pass

even after we told them not to, they deserved it: pop (deserve it); pop(deserve it).

The careful parentheticals and repetition lure the reader into what already feels like an alien world. But it’s a world, one in which an enemy must be created, that is also familiar: “In the beginning, Pineland was somewhat like the Soviet Union. Now, Pineland is somewhat like the Middle East.” This poem, “Pineland, in the Empire,” continues as Gypsy lists the names of role players as they fall down the page:

Laith.

Nafeesa.

Ahmed.

Hana.

Yusuf.

Omar.

Gypsy.

This poem includes the direction to “cue the theater,” and Stone often makes use of such theatrical language. At some points, she offers bracketed stage directions, and in another poem, “Matrix: Which is Which,” introduces the role players as if dramatis personae:

Ahmed owns a shop in the village. His son was killed by an [errant] Predator strike. Death of his son has never negatively affected his view of Coalition Forces & he just wants to be left alone.

:::

Hana, a mother, her eldest detained during night raid remains distraught b/c according to her her son was a good boy never did anything wrong why her son taken & where taken to

The questions who are we? and where are we? hang in the air above the unfolding drama. No one—and no action—is exactly as described. While Gypsy, the role players, and sometimes even the American soldiers evoke sympathy, there is a sense that reality and identity are no longer what they are, or what we as readers want them to be.

The book’s structure offers a fragmented narrative, and the conflict which drives this narrative is found in the agency of authority: who controls the bodies and minds of the role players? Specifically, Stone uses the body in “The Anthropologist” to establish the conflict between herself, an anthropologist and role player, and the soldiers commanding her:

they . . . ask me am I comfortable, do I want dessert and what do I think I know about them and do I know any Americans who went to war or don’t I and if I don’t who do I think I am, and do I agree that through my

stomach, they will get

my heart?

In one early poem, “Quadrant,” Stone introduces Omar, one of the role players in Pineland’s scenarios and a former translator during the Iraq War. In between instructions and at a stoppage in play, Omar offers comedic relief:

Omar shows me the knife, scimitar-curved, that hangs

on the wall at the police station. He takes down that knife, cradles it

like a guitar, plays a song.

This image, and many others like it in Kill Class disarms the atmosphere of its horror, even while calling attention to that horror. In “Broken-In Internet Café Room,” we see Omar from Gypsy’s perspective before the start of a scenario: “When the play begins, his face / is sent to sea.” Stone both deploys and deports her readers in a single phrase by identification with the role player.

In Kill Class, the reader finds it necessary to follow Gypsy’s journey from beginning to end, without escape. Pineland wants to be a world without consequence, but Stone gracefully refuses. Her poems do not keep readers from important and troubling details. Consider this epigraphic details from “Wound Kit,” which lists the contents of a “Simulaids Deluxe Casualty Simulation Kit”:

Stick-on Wounds: Eyeball (900), Foreign body protrusion (901), Eviscerated intestines (902), Large laceration, 5 cm (903), Medium laceration, 3 cm (904), Small laceration, 1 cm (905), Compound fractured tibia (906) …

Gypsy perseveres in this landscape of dramatized violence, even if a piece of herself is lost in the process. Each day as she leaves Pineland and drives back to the Motel Six, she suffers momentary flashbacks and cognitive displacements. In “Driving Out of the Woods to the Motel,” Gypsy confuses a Kia car dealership with “Killed-In-Action,” one of many such occurrences throughout the book. Neither fantasy nor reality is pleasurable anymore. As a role player, Gypsy must “return home” every day—engaging in a ritual of return real soldiers complete only at the end of a long deployment.

Kill Class is a lesson in the choices a poet makes to present the many refracted shards of the human psyche. Trauma is everywhere: given to us in lines one moment and emptiness the next. Stone widens spaces between stanzas. She organizes realities in stanzas that disintegrate mid-poem. She strives for continuity only to have that continuity confronted by the American soldiers “assigning roles” and giving orders. Kill Class doesn’t just give us poetry, it gives us the reality of how poetry is made—not linearly or temporally, but with the abducted mind, with the pantomimed body.

In a later poem, “Mass Casualty Event,” Stone presents the collections’ figurative identity in three enjambed sentences:

I am in war. No,

I am in a game

of war. No, I am in a painting.

This sense of displacement is dramatized in the collection’s title poem, and its strongest, “Kill Class” in which Gypsy courageously refuses her assigned role:

They have put aside the rabbit for me.

Commander: Gypsy, this is yours. Feed it. For now, feed it.

Further into the lesson of this “kill class,” Gypsy breaks character:

. . . I am not the most rugged person in the world,

and I am the only woman here,

and I would like to have a bit of control

over what I do and don’t do.Commander: Young lady, you have started out on the wrong foot.

Don’t tell me who you’re not.

Then, there’s a choice—Gypsy is presented with a rabbit and told one strike over the rabbit’s head with a heavy stick “ought to do it.” Her decision is painful and heroic:

Gypsy you need to kill the rabbit. Unfortunately

you do not have a choice.I have a choice. Let me be perfectly clear,

I say. It is not happening.

The poem’s final lines produce a haunting, sonic burden:

The men make a circle

The pines make a circle

You need to hold

the legs. They are tying together

the legs the animal

screaming They raise

the stick The legs are in

my arms The legs are in my arms

Reading Kill Class in a world driven by the pleasure or pain of illusion can sometimes be a challenge, but the book implores us to remain hopeful: our choices remain ours alone despite the overwhelming exterior forces. Kill Class calls us to find the game and see the game, the actual role we play, and make it “perfectly clear” that we have a choice. And the best choice we might make might be not to play at all. But I wonder—if our passivity remains transfixed to the palm-glow of a swiped up simulacrum of world disasters, grief, and war—would we notice the transition to non-choice in our culture? In that scenario, we’re told what game we are to play, what role we are to fill, and when, and how, we are to die.

—

Daniel Jenkins is a poet, editor, and teacher. His work has appeared in Lost River Literary Magazine, Up the Staircase Quarterly, Cold Mountain Review, The Potomac, JMWW, and Cathexis Northwest Press. He is a graduate of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College (poetry, ’18) and teaches writing at Northern Virginia Community College, Loudoun Campus. Daniel lives in Northern Virginia.