Sanctuary of Shared Selves

by Antonio Lopez | Contributing Writer

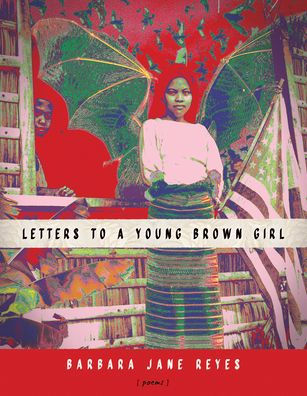

Letters to a Young Brown Girl

Barbara Jane Reyes

BOA Editions, 2020

Barbara Jane Reyes’s Letters to a Young Brown Girl (BOA, 2020) is a genre-bending collection, remixing mixtape, essay, poetry, & epistle to create a stunning tour de force of a book dedicated to Brown girls growing up in this cyber-spaced century of spectacle. Between the mounting pressures to post on social media, to dress according to the wishes of relatives, & epithets hurled by racist neighbors, a Filipina girl risks listening to everyone but herself. As a Chicano poet from East Palo Alto, a sister city just an hour’s drive shy of Reyes’s Oakland, I too am reflected & refracted, affirmed & ached, by this work.

In this, her sixth book, Reyes deftly shuttles from a direct second-person address to a (collective, unconscious) third-person “we.” The book is an archive of the body, plumbing histories of harm in order to show the ways Filipina women are forced to become estranged from themselves. As an immigrant Other, a woman with brown skin, a Filipina is epidermalized & aestheticized until she herself automatically practices her own policing. To put it another way, Letters to a Brown Girl is a document that dissects the forms of hate pervading a Filipina’s life. With it, Reyes constructs nothing short of a critical race theory of Filipina-American womanhood, interrogating the white neo colonial gaze that has exoticized Filipina bodies ever since the first Spanish ships shored into Cebu, ever since the changing of the colonial guard at the Treaty of Manila.

It is that guard, as Reyes is at pains to show, who has shapeshifted & changed his dress, but who has nevertheless remained sexually fixated on the Filipina: from the priest in his cassock & the conquistador in his armor to the camo-garbed American soldier—& all the way up to white Bay-area neighbors (in their capri pants & Sperry Topsiders) shouting “you people kept landing at SFO and goddam Mineta is named after you people / now.” To white culture, Brown people are perceived as pests, unruly migrants who’ve invaded & infested the Silicon Valley “and now everything smells like fried fish and feet.”

With her unflinching documentation of the working-class lives of Filipinxs, Reyes takes her place among a long list of vital Bay Area artists—E-40, Rocky Rivera, Trust Your Struggle Collective, Chinaka Hodge, to name a few—who champion the region’s most historically underrepresented communities. But going beyond the pale of statistical reports liberal politicians readily cite, Reyes humanizes Brown people, fleshes what is represented with bar graphs. She elevates poetry to its highest office, using it to portray a people in all their verve & vibrance.

In “Pakikipagkapwa-tao,” an untranslated subsection of the poem “Brown Girl Glossary of Terms,” she writes, “Kakayahan umunawa sa damdamin ng iba, for real. You know, like those syndicated, full-color photographs, of boys and men in LeBron James and Steph Curry jerseys, thinned flip-flops on their feet, one body together, shouldering a nation. One bamboo hut at a time.” There is little that I, as a poet or critic, can add to the beauty of these lines. What we witness is a dogged refusal to render oneself inferior. What Reyes rejects is a doctrine central to white supremacy, which is that the role of PoCs is to uphold Eurocentric norms. She starts in the realm of aesthetics & ends with the beauty in our brownness.

Reyes is unrivaled in her seamless jostling of several registers & references into a single narrative. In one of my favorite poems in the book, “Brown Girl Consumed,” Reyes explores the white American obsession with ethnic food, making it into a rhetorical opportunity to scrutinize the fetishization of Filipinx cultures. She begins the poem by imagining the late Anthony Bourdain roaming the streets of Manila for his show Parts Unknown (to whom?) in search of balut. When Reyes writes of him eating it, she puts it this way: “He throws / back his head and swallows Emily Dickinson’s beaked and feathered hope.” A recurring debate among contemporary poets of color is around how we engage with canonical figures, the ways we privilege their privilege at the expense of our lack thereof. What is remarkable about Reyes’s work is its answer, how it manages to engage with so many canons at once & with such calculated finesse, here splicing together that cinematic shot of Bourdain throwing his head back & Dickinson’s famous line, in effect re-envisioning the famed Filipinx street food as hope itself. This is a rewriting of entire traditions—across printed & visual media—in the blink of a line.

These acrobatics are not gratuitous, but part of the double & triple critiques necessary for liberation. For a Brown girl to realize her own self-worth, she must learn to demythologize white culture’s standards of beauty, standards projected onto bodies of people (and bodies of work). This overhaul of the poetic project is nowhere more clear than in “Brown Girl Glossary of Terms.” In the fourth section, “Pinoy,” Reyes offers the following:

You ever wonder about the sound of a poet rappin’ with ten thousand / carabaos in the dark? You ever eat fish and rice with your hands, off Styrofoam plates, in a hole in the wall, south of Market Street? What if that’s the poem, and you missed it, because you were looking for something roseate, effete, something that smells like prestige?

This is such a magnificent stanza, one that deserves some analysis. First, there is the sheer overwhelming awe of “ten thousand / carabaos” grazing the background of “a poet rappin.” This reference is to Al Robles, one of the fathers of Bay Area poetry, especially within the community of Filipinx-American literati. By interjecting the title of Robles’ debut collection into her poem, Reyes stakes her multiple genealogies, cross-fertilizing Dickinson & Robles & countless others outside the borders of poetry proper. (I picture Reyes as an M.C. from the 1990s, never hesitating to flex hypotactic syntax, stacking modifier on modifier to render an image in all its rich excess.) The simple phrase “off Styrofoam plates,” is crucial. It is an allusion to the condition of Filipinx people: classed & disposable. Then, right after it, “in a hole in the wall,” a phrase which reasserts the motif of place which is a mainstay in Reyes’s work. (Fans of Reyes will recall that her debut collection, five books ago, was titled Poeta en San Francisco.) Finally, we have that last line, which at first glance may seem tangential, but read in retrospect, we see that all its details are in fact the essence of the poem. With poetic sleight of hand, Reyes pushes the discourse beyond the limits of food & onto the economy of art itself—to which objects do we assign the most value?

Most poets relegate the ars poetica to a single poem. In Letters to a Young Brown Girl, it is the thread running throughout. By using the ars poetica as her primary mode, Reyes transfers the onus of valuation from herself to her readers, who, depending on their notion of what constitutes “good poetry,” may or may not have effectively “missed it.” In any case, for Reyes, there is no need to artify herself. She has been making art this whole time. Her work compels us to decolonize, through questioning, the institutionalized rubrics through which we judge “good poetry,” those unspoken criteria reinforced in MFA programs, writing conferences, literary prizes, distinguished panels & judges, & other sites of so-called erudition.

But Reyes doesn’t just deploy “military-grade shade” against her array of aggressors. She is equally critical of the traditions within her own diaspora(s), particularly in the ways they perpetuate violence against girlhood. Let’s turn to the series, “Brown Girl Breaking,” which serves as a subtle & powerful counterpart to “Brown Girl Glossary.” Under the passage on tradition, she writes, “Remember when they said, until a boy is born to a couple, they must not stop bearing children. It is tradition. They meant you were surplus.” While the Filipina is hyper-sexualized by the white male gaze, her Filipino counterpart de-sexualizes her, acting on the opposite end of the same objectifying spectrum. She is a receptacle. She is a commodity. The language here reads like a handbook, full of instruction (“Cook rice (measure the water up to the first knuckle…”) & supplication (“May you be farmed, collected, propagated by gentle cutting… May coins exchange hands / in the speeding streets for you”) The specter of femicide haunts these passages, as they elicit a rite brown girls undergo: the division of labor demarcated on rigid gender lines. The refrain of “may” intimates prayer, elevating this quotidian violence against brown girl’s labor as divine, and therefore all that more difficult to deny. The tone throughout is both unemotional & maternal, a combination that is, to say the least, unnerving. But what tenderizes this numbness is Reyes’s turn to the lyric. Later in the same poem, Reyes writes, “Remember when they said, you must never slouch, ladies. You must always bend. When / a bamboo reaches its highest peak, it bends back down to the soil . . . And the body will be a haven they claim.”

But deconstruction alone, however beautifully rendered, won’t liberate the Brown girl, nor will multiple indictments. Only the transformation of self can liberate a Brown girl. Reyes explores Filipina adolescence in “Brown Girl Mixtape.” As the book’s middle section, it pairs song with poem, an interplay which suggests the speaker’s emerging interiority. Reyes’ previously biting, tongue-in-cheek tone is replaced here with a tenderness which works to conjure a spiritual gathering of sisters in every shade of hurt. “How do you fill / a vessel of want?” asks one poem in this section; “How old were you when you knew you were the ocean?” asks another. These poems are queries that quarry the traumatized self. The section is quiet, incantatory, world-making. It is at its root a heartfelt call for vulnerability, to “slough away the layers of white noise. The sting when exposed anew.”

Reyes’s poems are x-rays [x-Reyes?] into a classed & raced interiority, one that traverses beyond the Filipina & onto Brown bodies en masse. The Mexicans & Salvadorans & Guatemalans & Samoans & Tongans & Black Americans of my hometown are all x-rayed by this phrase: “Inside the body that is our overcrowded house . . .” The author’s “our” here is a pronoun whose latitude & landscape houses multitudes. Her pages are not pages, but scrolls, lusciously long-winded & Whitman-esque in their exploration of an “I” that is more & more a census of all us Brown homies. Reyes is our laureate. Her “I” surveys the decrepit streets of our (neighbor)hoods. Amidst the racist vitriol hurled at Brown, Black, & Native people, Reyes pauses to witness our tenderness, which testifies that, despite what presidents & police precincts say, we are indeed human. She writes (of whites), “there are so many of you, you’ve snatched up all the houses you built over the old orchards you picked the apricots / gladiolas and almonds, we remember flowers and the dragonflies . . .” It is an achingly beautiful thing to render floral & fauna as the enjambment to racism. And yet, this is the American pastoral of our moment. Not what is happening in the US, but what is happening within us. Were not our mothers asked, “Why can’t she just speak English”? Were not our fathers told to “fix your busted cars in the driveway parked on the weeds in your junk front yard . . .”? With this book Reyes has gifted us a Bay Area documentary, an examination of how the discourses of immigration, housing, ethnicity & economic inequality in our counties all collapse in the throats of emboldened xenophobes. But Reyes hesitates to unite us simply as mutual victims of white supremacy. With this book, Reyes has decidedly not created a work of literature, but what I am clumsily coining loób-ature, a literary grafting of disparate materials, the tactic of her elders, those “experts at third world improvisation.” Diaspora causes a kind of cultural orphaning, one felt by all us migrant babies. “But there is so much sadness,” Reyes reflects in the book’s final poem, “being so torn from my elders and kin.”

Against amputation, Reyes offers stitch, a communal refashioning of self with others, what is known in Filipino studies as kapwa—“a sanctuary of shared selves”—and loób—what scholar Jeremiah Reyes (no relation) calls “relational will.” I think of Letters to a Young Brown Girl not as a book, but bricolage, inspired less by the secular toolkits of craft than the indigenous practices of Reyes’ own culture(s). Toward the end of the collection, the speaker invokes her father, his “love for swap meets and junkyards,” as an archetype through which poets of color, oftentimes the children of immigrants or immigrants ourselves, may unlearn our aspiration for whiteness, our fantasies for their “lived matching Tupperware lives,”and learn to honor our own traditions. Doing so, Reyes admits, would require intellectual humility, hence the author’s quiet declaration, “I think we should start asking again; I think we should start asking again why.” I love these final words, this final poem, as they straddle multiple genres at once—essay, memoir, the list-as-poem—to teach us what our art doesn’t have to be: pithy, flashy, erudite. It must, above all else, liberate. This book is at bottom a love letter to all the working-class brown babies of the Bay Area.

Gracias querida Barbara, for this brown-print for our liberation.

Tuyo,

Antonio

—

Antonio López‘s debut collection, Gentefication, was selected by Gregory Pardlo as the winner of the 2019 Levis Prize in Poetry and will be published through Four Way Books in September 2021. Born and raised in East Palo Alto, CA, he has received scholarships to attend the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, Tin House, the Vermont Studio Center, and Bread Loaf. He is a proud member of the Macondo Writers Workshop and a CantoMundo Fellow. His nonfiction has been featured or is forthcoming in PEN/America, Jacket2, and Insider Higher Education, and his poetry in The New Republic, Tin House, and elsewhere. He holds degrees from Duke University, Rutgers-Newark, and the University of Oxford. He is pursuing a PhD in Modern Thought and Literature at Stanford University. Antonio is currently fighting gentrification in his hometown as the newest and youngest council member for the City of East Palo Alto.

Barbara Jane Reyes is the author of Letters to a Young Brown Girl (BOA Editions, Ltd., 2020). She was born in Manila, Philippines, raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, and is the author of five previous collections of poetry, Gravities of Center (Arkipelago Books, 2003), Poeta en San Francisco (Tinfish Press, 2005), which received the James Laughlin Award of the Academy of American Poets, Diwata (BOA Editions, Ltd., 2010), which received the Global Filipino Literary Award for Poetry, To Love as Aswang (Philippine American Writers and Artists, Inc., 2015), and Invocation to Daughters (City Lights Publishers, 2017).