Review & Interview // “Scent as Summons”: A Conversation with Elizabeth A. I. Powell and Review of Atomizer

by Carlene Kucharczyk | Contributing Writer

Louisiana State University Press, September 2020

Reading Atomizer is like going on a scent tour of someone’s life, through their deep past and their memory, with a person who is particularly attuned to their sense of smell and has the words to describe these transportive scents to you. It will likely make you wonder about the scents that make up your own life. Which is most evocative? When you close your eyes, is there something that comes to mind? Author Elizabeth A. I. Powell has an uncanny ability to remember these smells and to summon the memories, recent and long ago, that go along with them, inviting us, in this book, to join her. “The romance of smell overcame me, scent meant love, and produced spells,” she writes early in the book in the “Base Notes” section of the title poem. I have never read a book quite like this.

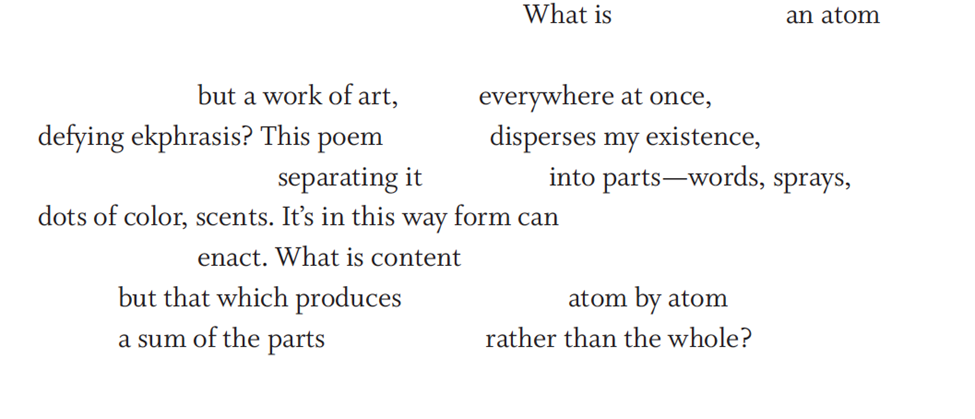

The voice is questioning but not judging as these poems relish in generous personal honesty while serving as a critique of our society. They invoke how we live in isolated boxes: our cars, houses, only seeing each other in pixelated portions over screens. But this is all conjured with the backdrop of a rich sensory landscape that we can choose to be more attuned to. The poems in Atomizer are full of lure and voice, sharp and witty, conjuring, philosophical, heady, but with heart notes, as in this excerpt from “Poem with Atoms in It”:

Published in September 2020, six months into the global pandemic, this book takes on a new role, as many people temporarily, and some ongoingly, lost their sense of smell due to covid. However, though smell is often considered the most evocative sense, it is also perhaps the most underappreciated one—that is, until it’s gone—as is discussed in this New York Times audio story “The Forgotten Sense.” It is also perhaps the most mysterious and least understood one, described in this Harper’s article “The Odor of Things.”

A prompt to take with you, as you exit this box on your phone or computer, or as you leave the page: pay attention to the smells you encounter in a given day, writing them down in a list if you wish, and then proceed to write a poem that includes and expands on the most evocative one, Elizabeth A. I. Powell-style.

Carlene Kucharczyk (CK): When did this book begin for you? When did you know you were writing it?

Elizabeth A. I. Powell (EP): This book began writing itself in me as an etching left in memory, particularly around growing up around olfactory art, and spending a lot of time as a child in a perfume shop. Later in life, when I returned to the planet of perfume, I began to explore how my conversation with scent had taken shape and produced a narrative over my lifetime. I truly believe the book writes you and then you write the book, meaning (as Rilke said) we must live the questions of our lives, that is our way into art. When the correlation between my ideas of science and my ideas of beauty/art collided, I knew I was then really writing the book. First, I had to live through some trauma and reconciliation with the world I didn’t understand. Not that I understand it now. Life goes by narrative sections, perhaps. I always loved Ernest Hemingway’s Iceberg principle, you know ⅞ of everything is beneath the surface. For me top, middle and base notes were a way to register levels of meaning, by how a smell, like music or poetry, had different registers. I liked the idea that all things, not just perfume, had emotional top, middle and base notes. Smell as iceberg.

CK: Is there a particular question that drove this book? Or a question you sought to answer with it?

EP: How do all the atoms and particles floating around compose and recompose things? And we know from WC Williams, no ideas but in things. You know the way light tangos with dust? It felt like that was how I saw things all through my childhood. I had a sense nothing was solid, but I didn’t know much about science or spirituality then. When I was in middle school and saw examples of pointilist art with my scientist/mentor grandfather, I began to have a vocabulary about how art depicts the flimsy, unsolid veil of things in the material world. In some ways I think the image is how we address emotional movement and atomic movement in an object. The central question of this book started out as a conversation I was having in my head with Alain Badiou and his book In Praise of Love: How far from our biology we will go with technology and what does that mean for love? I tried to perform what Badiou referred to in that book as “truth procedures” on all the crazy narratives that emanate from 21st century America. The four truth procedures Badiou talks about are art, science, politics, and love, where genuine events can be produced, rather than marketed events that try to push a meaning that may or may not be. Perfume is actually an olfactory art where scent images are reproduced into an artistic vision, but also perfume is a way to deceive and manufacture. I tried to interrogate that as a philosophical exercise about what it means to live and how you can or cannot trust yourself and your senses. We all want certainty, but as Badiou says: “Love without risk is an impossibility, like war without death.” All my poems are a tango with how to be.

CK: Have you always been highly attuned to your sense of smell? Is it the most evocative sense for you?

EP: When I was pregnant with my kids, it seemed like I could smell things through the freezer from a good distance. I wasn’t pleased about that. Sometimes I smell things in my dream-life, like fire, which is frightening. Having a strong sense of smell allows one to decipher certain truths about a thing, unless one has detached from oneself.

CK: If you had to choose one scent to encapsulate your life, what would it be? (Sorry, hard question.)

EP: It would have to be the scent of the tops of my children’s heads when they were babies, but also the smell of their hair when I hug them now.

CK: Is there something you are still trying to figure out the smell of but haven’t yet?

EP: Yes. Fingernails. Ideas.

CK: Where will your sense of smell lead you next as far as your writing goes?

EP: Writing sense images that are linked to scent rather than just sight has made me more attuned and open to using all the senses I can in my writing.

CK: What does synthesia look like for you?

EP: Language itself is a kind of synthesia, so are metaphor and simile. Sometimes I experience taste and touch as color.

–

Elizabeth A.I. Powell is the author of three books of poems, most recently Atomizer (LSU Press). Her second book of poems, Willy Loman’s Reckless Daughter: Living Truthfully Under Imaginary Circumstances was a “Books We Love 2016” by The New Yorker. The Boston Globe has called her recent work “wry and fervent” and “awash in synesthesiastic revelation.” Her novel, Concerning the Holy Ghost’s Interpretation of JCrew Catalogues was published in 2019 in the U.K. Recent poems appear or are forthcoming in The New Republic, American Poetry Review, Women’s Review of Books, among others. She is Editor of Green Mountains Review, and Professor of Creative Writing at Northern Vermont University. Find her at www.elizabethaipowell.com

Carlene Kucharczyk is a poet and essayist living in Vermont. She was the Henry David Thoreau Fellow at the Vermont Studio Center and the Writer-in-Residence at the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site, and holds an MFA from North Carolina State University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Mid-American Review, Conduit, Green Mountains Review Online, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.