Reclaiming Materiality

by Greg Bem | Contributing Writer

Ensō

Shin Yu Pai

Entre Ríos Books, 2020

Michael Leong’s introduction to Shin Yu Pai’s expansive new collection describes the concept of “Ensō” as “a document of auto-curation that honors both product and process.” Readers of Ensō will discover not only individual works serving as an isolated and emergent ensō, but also an ongoing, developing worldview. In Ensō’s opening poem, “Devotion,” Shin Yu Pai writes:

a keepsake activated &

sanctified so long ago,this token

I held back for myself

The book traces Pai’s journey as an artist and human, and documents the creation of these “tokens” through commitment, intentionality, and devotion. In this sense, Ensō is an alignment between the poet’s sacred and private acts those that are borderless and public. Pai writes in the introduction the book:

I was not attached to being a poet, but interested in using the instrument of language to make sense of the world. It has seemed fitting that this exploration should take more than one form, ever conscious of the presence and absence of language, the medium to which I feel most connected in spirit.

The book consists of ten sections that explore different elements of Pai’s work, often organized around themes, media, or formats. In the book’s first section, “Sixteen Pillars,” Pai describes her history with Gallery 109 at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she, as a newcomer to the city, endeavored to connect with a specific place over time. One result of this project is the poem, “The Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion,” which describes the gallery scene:

Entering a darkened room

to pass between sixteen pillars

of equal height and depth,

ten feet high and one foot square.

The language here is often typical of Pai’s writing: stern, focused, and exquisitely concrete. What might appear to be on the surface slightly impersonal reveals at its core to be the result of the humane act of presence, of being present. Pai explores her relationship with this place over time, including examining the reality of the male-dominated curatorship within the gallery. This type of accountability is a motif within the book; Pai consistently questions power and historical supremacy throughout most of her projects, often as a way to find her own independence and position as an artist. In the case of Gallery 109, Pai continues to find importance in her relationship with the gallery even after she leaves it. Years later, she reflects on her earlier poem:

The poems that I’d written back then and now were my way of disrupting the silence of these informational time capsules put forth by art curators. The poems were my effort to open up a space and time beyond what the label prescribed, to create something distinct from what was visibly enshrined, translating the other into a language of self. Finding beauty in absence, coming home to both longing and belonging.

Each section of Ensō is similarly insightful, often overlapping by connecting one art project to the next. For instance, Pai explores her relationship to the haiku form and various projects that utilized haiku; which is then connected to a discussion of her history with bookmaking; and then to her radical, transformative moments in motherhood; and even further to her examination of the history of Redmond, Washington, and discussion of it through chlorophyll prints on leaves. From there, there’s an obvious connection to Pai’s “Heirloom” project, in which Pai imprinted fruit with text. Each of these links, among the others contained in Ensō, form the book and inform the reader.

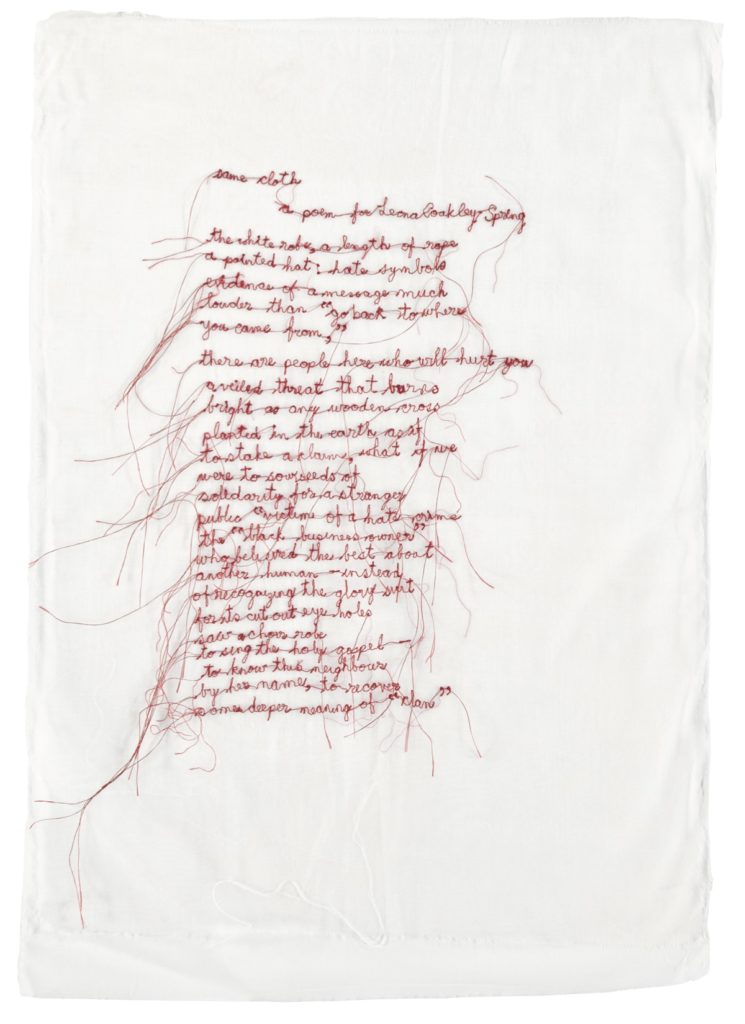

One dilemma inherent in Ensō has to do with the potential difficulty of representing the multidisciplinary, multimedia, and incredibly tactile and temporal art in text. But Pai affords the reader the chance to get close to the work by exploring its personal elements and documenting the process of its generation. Near the end of the book, especially, in a section called “Same Cloth,” Pai invites the reader to join a beautiful and terrifying reality of poetry. She opens the section by saying:

Reclaiming the materiality of the textile was a means of subverting the static quality of the printed page to evoke the language of lived trauma and to make that pain tactile and visible.

In this section, Pai begins by “[thinking] deeply about how one can publicly address wounds in the community born of injustice and intergenerational trauma” after discovering that a black consignment shop owner is left KKK robes by a white man, and soon thereafter closes her shop and burns the robes. The lack of justice in this series of actions is troublesome. Pai remembers confronting the Confederate flag in Texas, put up by neighbors soon after they moved into their apartment, recounts being unsafe, admits to being stalked and soon after being mistreated by the detective assigned to her case. In responding to this sequence of events, and the absence of justice, Pai attempts to create a poem that speaks to the real, living community. This poem, captured as a photograph within Ensō, was made with cotton embroidered on silk organza. As Pai explains, “I wanted a physical object that could reclaim the cloth and invoke a visceral experience.”

Ensō ultimately becomes a physical object of reclamation as well. To what degree Pai intended for this book to be affective in a bodily way, a movement of the spirit of sorts, is uncertain, but the reach into the personal and the pull across time and space is a powerful, enduring method for representing one’s work. I tend to think too intensively on the lack of brevity of works in our era of a collective Twitter and Tumblr poetics. But Ensō demonstrates art that is charged through time and space, maturely, and for that I am grateful, inspired to be left, as Pai writes in “Splintered,” “sifting through the leaden heft of language.”

—

Greg Bem is a poet, multimedia artist, and academic librarian living on a ridge above a tunnel above Lake Washington in Seattle, Washington. His reviews have been featured in Rain Taxi and North of Oxford. He is the author of Of Spray and Mist (forthcoming from Hand to Mouth Press), and the co-author with Burmese poet Maung Day of 2019’s bilingual Like salt. Like a spine. His verse sequence on colonialism in the Pacific Northwest, “Bountiful Sound,” was featured in Ravenna Press’s Triples 11 alongside the work of Kat Meads, Samuel Ace, and Maureen Seaton.