PoNW’s Favorites | Spring 2025

Spring poetry is bountiful, with the season previewed here in staff favorites.

In debuts, Late to the Search Party by Steven Espada Dawson (May, Scribner) has a true arc and a true soul. Its central question is whether a brother missing for ten years is to be grieved as away or be grieved as dead: in the speaker’s memory, details echo and images clarify, but the heartbreak of wondering compounds. The writer seems ever in awe of poetry’s potential, and of life’s short span—to cancer, addiction; these collide in a beautiful debut that calls out: “I want so badly to write words // with a future attached.” The collection is the first from Scribner’s poetry series and marks the first book that came through an un-agented, open submissions process, after the series that launched in 2023 with Airea D. Matthews’s second book Bread and Circus and Sam Sax’s Pig.

come from by janan alexandra (Apr., BOA) proves that to watch is to change: the love of strangers, and the strange, is at the heart of the poet’s attentive, original gaze. In these wondrous poems, food, touch, and dreams burst into angels, colors, and potential, just as love is shared openly and ferociously with cats, flight attendants, and strangers. As Arabic letters come alive, words have many definitions, and a notable “parable” series expands story logic, the collection never forgets the weight of language—or of dates.

Little Mercy by Robin Walter (Apr., Graywolf) is an unflustered, exquisite debut that declares in one of its many strong, sure lines that seem truest in their calm unfolding: “Still, the day opens.” The whole book is a series of constant, further, and deeper openings, twigs under stillness and rivers under skin. The successful collection joins the Academy of American Poets First Book Award and its many stars, including last year’s gorgeous The Blue Mimes by Sara Daniele Rivera and the stellar The Wild Fox of Yemen by Threa Almontaser.

Two others debuting stylishly: Salvage by Hedgie Choi (Apr., Wisconsin) and We Contain Landscapes by Patrycja Humienik (Mar., Tin House) are inventive, funny, and collaborative, positioning poetry as connected to friendship—writing from, with, and to poet friends, making more lively the pages they seem to read. Choi’s collection is full of estranged aphorisms and sketched observations, like the girl whose bangs are in a roller all the time for some future of bouncy bangs the speaker never sees or the mechanics of the childhood competition she has with a younger sister to circle desired items in the Sears catalog. Humienik claims to “play with feeling, / but I can never remember the ending,” but remembers endings of all kinds—of place, time, and hope. In sonnet crowns and epistles, the poems, like the speaker with a friend, stays “up late making up our own prayers,” realizing at last that all prayer is manufactured by someone.

More established poets also add to their work’s bodies. Primordial by Mai Der Vang (Mar., Graywolf) marks another splendid triumph for the poet. By bringing to the page the saola (an endangered, almost never seen animal mostly in Southeast Asia) alongside a maturing “I,” it brings language to all the lives, places, and histories unseen. The collection delights in exploding known forms and creating new aesthetics as it considers what is environmentally human, animal, and landscape. Her language is focused and luscious, with never a word or a space out of place: “It may be that we are stolen of each other.”

I Imagine I Been Science Fiction Always by Douglas Kearney (Apr., Wave) understands speculation and storytelling as a spectacle of past, present, and future. In a concentrated, indelible new collection, poems with visual vigor exceed the page and turn into the third dimension with the depth of perception, and into the fourth dimension in acknowledging the audience. Any quote would fail to be a true microcosm of this umsummarizable book that adds to a beautiful body of work, but one is close: “Speculative don’t always turn out fi.”

In a much-anticipated follow-up, Becoming Ghost by Cathy Linh Che (Apr., Washington Square) uses scripts, lines, and cuts to grasp structural and colonial violence alongside familial and interpersonal violence, and the use of images and stories in each. The poet’s parents were cast into the background of the movie Apocalypse Now and poems imagine into the parents’, but also the daughter’s, consciousnesses. Golden shovels and dialogues connect the lived and imagined apocalypses between big-budget film and COVID-era Costco, from Vietnam to Palestine. “We were diligent in our portrayal,” says a parent speaker. So, too, is this collection: diligent not toward facts but toward feeling, irony, hungry for absence and its meaning.

Concerning the Angels by Rafael Alberti, translated by John Murillo (Mar., Four Way) presents pithy, pleasurable poems from 1929 Spain that feel fresh and generous. In his introduction, Murillo notes that the volume was understood as an artistic pivot, a stylistic shift, and this sense of constant possibility drives in English; in Murillo’s words, “If these were poems drafted in the dark, they were also poems thought through, worked for, and revised in the full light of day.”

I Hope This Helps by Samiya Bashir (May, Nightboat) is a thrilling fourth collection that lovers of Field Theories will cherish and be changed by. With active experiments in time, font, and voice, Bashir assuredly takes on geography as a function and proves that the poet never stops moving, gifting confidences and realities in that process: “And we are here. / And we are making.”

Interstitial Archaeology by Felicia Zamora (Apr., Wisconsin) maps explanations of the world, from medical studies to family histories, whether masturbating next to a sleeping partner or erasing a summary on climate change directed at policymakers. In repetition and in form, the poems (sometimes essayistic and braiding) are anxious for belief.

The observant and electric Into the Hush by Arthur Sze (Apr., Copper Canyon) views any environment, natural or made, as dynamic. A work that acknowledges all the poems that came before to make it possible, the accomplished poet indicates how a narrow field of poetry may offer a wider and deeper view.

Making a Living by Rosalie Moffett (Mar., Milkweed) wonders gorgeously about the crossings of parenting and consumerism: how the making of a life resists materialism, but how much the role requires making a living. With keen but somehow understated language, the poet points to the body’s crossings with the supply and money chains, at “the heart / of the fulfillment center” or “When empty / -handed” in “the eye of a needle.”

Red Wilderness by Aaron Coleman (Mar., Four Way) makes music of address in poems for ancestors, with epigraphs by James Wright or Rabindranath Tagore. Every poem is a complication for the map, never a solution and never a border. The impressive and sedulous second collection never falters from wound or wild in these anti-imperial, definitively bodily works: “Tear // at the scab and / let each tear teach you.”

The University of Arkansas Press has two remarkable series centering new poetry, with new collections out this spring including Lena Moses-Schmitt’s True Mistakes (Mar.). The debut looks on at the future and the idea of the future with great curiosity, addressing a “future me” and recounting the futures that didn’t get to be via the past. Looking back at the future from their memories, the poems report on transformations and, in their wild dispatches, become them too.

The book comes through the Miller Williams Poetry Series, awarded since 1991 and edited by Patricia Smith since 2020. The prize publishes not only the winner’s poetry collection but multiple finalists each year, including Moses-Schmitt, as well as Saba Keramati’s 2024 Self-Mythology. Smith names Keramati’s work a successful emblem of “our hyphenated selves”—the halves and twins and their scars. The poet’s use of centos, abecedarian, haibun, and ghazal remind how form is enlivening and distancing at once: “my own other.” The multiple selves awake in scenes of shaved legs and miscarried firsts, the gaps of inheritance and translated tongues.

Architect by Alison Thumel, the most recent winner of the series, is another painfully beautiful and beautifully painful debut that innovates and turns; its opening poem ends “Inside a memory // is its ruin. / Inside ruin, what?” The rest of the collection continues with the same tightness of language and concern around memorial.

Also housed in the press is the Etel Adnan Poetry Series edited by Hayan Charara and Fady Joudah, which turns 10 years old this year and is awarded to a first or second book of poems to a writer of Arab heritage. A Theory of Birds by Zaina Alsous is a beloved 2019 winner of the series, a collection confident in language’s capacity to become new with methodical, affecting lines like: “I mourn myself / by disappearing without prompt.” The 2020 Strip is another memorable and glamorous winner, in which Jessica Abughattas breezily riffs on Shakespeare or Plath, becomes a poet of praise and cultural critique at the same time, or humor and walking. Her collection embodies the Marie Howe line “Anything I’ve ever tried to keep by force I’ve lost”—from scenes to words, from selves to hopes—and always with play, as when Prufrock becomes frock, legend made into dressing. She asks, devoid of melodrama: “Do you want to be loved or understood?”

The most recent 2024 winner Umbilical Discord by Rawand Mustafa evokes a collective narrative with Palestinian women’s testimonies from the 1948 Nakba (“there is no postwar”), a weaving of quotes and actions that refuses to hold the prism of only one point or person. For the Palestinian Syrian poet curious about the prefix of memory and etymology of story, “time is a place / within and / without me” in this translation, collaboration, and true collection.

Unfortunately, because of a 2017 law, any contractors of public Arkansas institutions can receive their payments only when they sign a pledge that they will never participate in BDS. This is based on a state-wide law, not a rule of the press or university, but has impacted many poets who refuse to sign such a pledge and cannot receive honoraria for academic talks or royalties for their books.

This March the still-new (2016-founded) Fonograf Editions adds three stunning books to its roster which includes Nathaniel Mackey, Cody-Rose Clevidence, and Alice Notley among poetry and LPs. In Arrangements by Esther Kondo Heller, words in their reminders and remainders transmute: in mutter is contained the mother, the mumble, the muted, the utterance; and in any image crossed with text there is the potential of performance. This is poetry that does not describe but acts, lives, and knows. Perfectly arranged, this collection powers and glides. Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah is engaging, controlled, and irrepressible, while If Only for A Moment (I’ll Never Be Young Again) by Jaime Gil de Biedma and translated by James Nolan provides a brisk and succinct bilingual selected volume of the Spanish poet.

Several selected volumes of important poets begin to gather the totality of a writing life into one binding:

The Essential C. D. Wright (May, Copper Canyon) brings together poems selected from across the author’s many books as well as unpublished poems and drafts, including lovely hauntings like “The great nothing was there. Always. / Listen, Trespasser.” In the introduction, Forrest Gander writes of living together for over three decades, “she was not for one minute uninteresting. Or uninterested.” Wright’s desirous, interested, wild eye is more present here than in any other single volume.

Two selected volumes arrive in March from New Directions: Love Is a Dangerous Word by Essex Hemphill is as comfortably chatty as it is heartbreaking reminding that “Even hope is a device”; each poem is somehow prescient and new at once, writing of desire and death and daylight. The Eternal Dice by César Vallejo, translated by Margaret Jull Costa provides a concise and thoughtfully arranged volume that honors the important Peruvian poet.

Water by Rumi, translated by Haleh Liza Gafori (Apr., NYRB) is a beautiful follow-up to Gafori’s first translation Gold. Gafori’s translations are fluid, original, quiet phenomena; her thoughtful care shines through every poem. The slim volume continues the exciting work of returning Rumi to his roots and words, including the reference to a sheik that has been edited out of other translations.

Circumpolar Connections edited by Liisa-Rávná Finbog, Joan Naviyuk Kane, and Johannes Riquet (Mar., Wesleyan) brings together works not only different indigenous writers and artists to question and expand notions of geography and belonging, but also different genres and languages, times and spaces.

As always, volumes of prose also illuminate poets, most notably The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong (May, Penguin). The novel is a tender, energetic novel concentrating on relationships outside the structures considered necessary, in particular on a young man about to descend from a bridge, an old woman about to descend in her mind. Two people on the edge gather to build a corner, and then corners multiply into dimensions, a geography of love and panic and humor between them. Within these four hundred loving pages are both natural environments and capitalistic ones on their own edges detailed with intense precision, as well as nights too busy for prayer and songs and movies on loop. The wide, accomplished novel indicates an exciting shift in content and style, though Vuong is known to write in letters, directly or indirectly. At a critical moment late in the novel, a line seems to sum up its ethic and aesthetic: “Somehow there was music.”

The book is Vuong’s fourth overall, with the most recent poetry collection, Time Is a Mother from 2022, also shifting from his first, with griefs in many fragments represented in language and mind. One motif is the anaphora of “Because” at the start of a stanza, as though the book hopes for reason and so creates it. Time took the exciting, original pulse of his first and developed its style, or craft, in more conscious ways, and imagined that death, in language, is not only metaphor, since “Words, the prophets / tell us, destroy / nothing they can’t / rebuild.”

In the Rhododendrons by Heather Christle (Apr., Algonquin) is an emotional memoir that also serves as an individual intellectual history, moving between generalizations about what poets love and how people are and highly specific scenes of (dis)connection, (un)realization, and the Wo(o)lf that guides. In clear, sometimes even fun prose, Christle wonders how violence relates to inheritance.

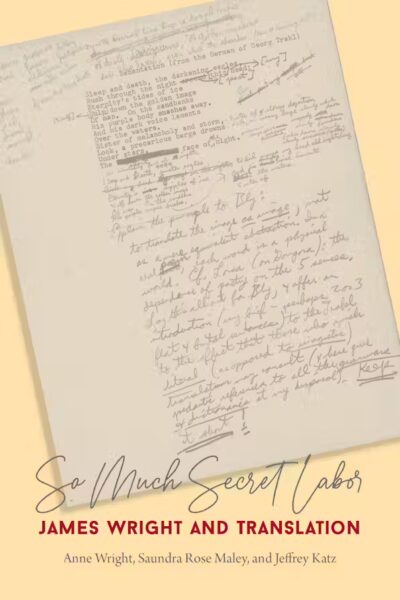

So Much Secret Labor: James Wright and Translation by Anne Wright, Saundra Rose Maley, and Jeffrey Katz (Mar., Wesleyan) seeks gracefully to indicate how translation impacted Wright’s work, using primary sources and purposeful arrangements. The academic text grows to feel like a flexible yet definitive guide on James Wright’s very mind, as well as evidence that great poetry is birthed by obsessive interest in connections between and within languages.

Edited by Cindy Juyoung Ok