“The Octopus Prophet”

This post is first in a series featuring Pushcart Prize-nominated poems from recent issues of Poetry Northwest. First up: Paula Closson Buck’s “The Octopus Prophet,” introduced by the poet.

The older I get, the more I think animals speak to our humanity in strange and beautiful ways. And so, a couple of years ago, I began putting together a bestiary.

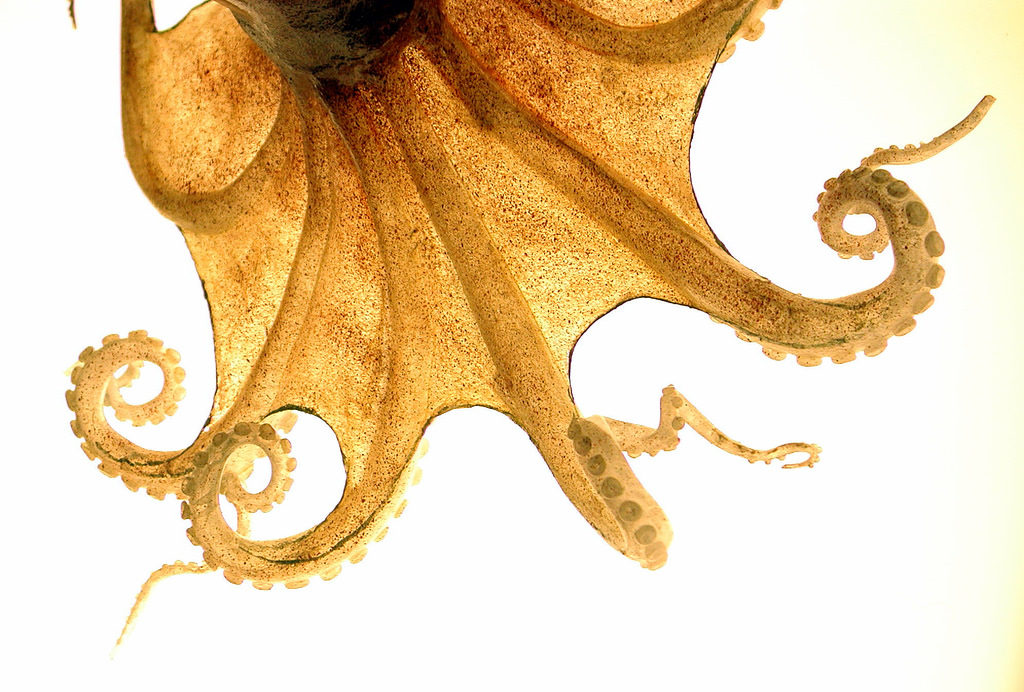

This particular poem grew out of a moment of delight in seeing a flimsy pink octopus play an incidental role in a fresco depicting the Second Coming. The fresco was preserved on the wall of a Byzantine chapel in the mountains of Cyprus, and the effect on me of its “creature feature”—the element of the scene that I most trusted as inspired by the artist’s reality—was uncanny. Ibought the guidebook just so I could keep looking at that weirdly pink octopus. And then I began listening to it too. I allowed myself to be led by it.

Where it led was to a recalibrating of my sense of how dark the dreams that define us as human beings can be. By dreams, I mean not only phantasms but also empowering aspirations.

What began as merely a voice of observation in the poem evolved into a voice of revelation (or anti-Revelation), and the little pink octopus became, to my surprise, prophetic. As a writer, I was happy to submit to its humble authority, derived not from the hegemony of religion but from flawed art and the no-harm-intended natural world. The dire circumstance to which it speaks keeps refreshing itself in the world around me.

The Octopus Prophet

I saw a small pink octopus on Judgment Day.

It was painted on the chapel wall amid frescoed waves,

the work of an island amateur.

I saw it caught in the teleological crossfire

while bodies stood up from graves

as if from their bathtubs—surprised by strangers—

or when waking after dark from a long and poorly timed sleep.

On land, lions and griffins bore folk in many directions,

valiant in the service of an elaborate system

of blame. The octopus, familiar with the drowned,

hung amid scalloped waves like a cosmic hand towel,

pink and weirded by the artist’s hand.

Pressed against the occipital bulb of its head

was the head of a man, the face and some of the hair, and though

a caption in my guidebook said it was disgorging

the head, the octopus seemed rather to be drying it

gently, or bumping it along toward some vague reunion.

While men were dreaming of vindication and women

pleading guilty on all counts, I saw a new Heaven

and a new Earth. And I saw that blithe, pink octopus with eight arms

orchestrating nothing, eight arms of animalian

letting go—the only protagonist in that scenario.

Like the housefly that acts as a kind of prophet in a trompe l’oeil,

persuading us what we’re seeing is real.

Though of course, it isn’t. We know this especially

if the artist’s skill has failed, which in the case of the octopus,

as I said, it had. So I knew there was no afterlife

though all the hatches were flung open,

all the sorry bones unpacked for eternity. And in its mutinous

wisdom, from the stylized deep the octopus chided none of us

in particular when it cried amidst the waste and the glory

Have you lost your head? While the face—

the face just bumped along, furrowed in shame,

swept by a heinous collective dream.

—

Paula Closson Buck is the author of two books of poems from LSU Press and, most recently, a novel called Summer on the Cold War Planet. Her poems and stories have appeared recently in Crazyhorse, Gettysburg Review, Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, and Southern Review. A former editor of West Branch, she directs the Creative Writing Program at Bucknell University.

“The Octopus Prophet” first appeared in the Summer & Fall 2016 issue of Poetry Northwest.

—

photo credit: neurmadic aesthetic Glassopod via photopin (license)