Our Chart of Consequence

by Torin Jensen | Contributing Writer

Though We Bled Meticulously

Josh Fomon

Black Ocean, 2016

The Hirshhorn’s 2013-14 exhibition “Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950” was a wide-ranging look at artistic responses to the particularly human talent for destruction, apocalyptic and playful alike. There were a number of pieces addressing the nuclear bomb, a slow-motion video of a bullet shattering a vase, Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece,” and Ai Weiwei’s “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995),” among many others. In the Hirshhorn’s circular exhibition space, the show took on a tone of inevitability; humans have destroyed and will continue to do so for as long as we’re human. Leave it to the artists to at least press pause and strip the idea of its parts and take a good long look at how beautiful, rotten, and innate such an instinct really is.

“Damage Control” and Josh Fomon’s debut poetry collection, Though We Bled Meticulously, are, for me, intimately connected. On a personal level, Fomon and I visited the exhibition several times together, partly out of a fondness for the Hirshhorn (it’s usually delightfully quiet) and partly out of a need to disrupt our mutual and increasingly despairing search for full-time work. I had read some early parts of what eventually became Though We Bled Meticulously, and though I can’t say with certainty how big a part the “Damage Control” exhibition played in the final manuscript, they were roughly concurrent. The book and exhibition share a piercing drive to examine and, perhaps, unravel and freeze the entropic nature of construction, whether lyrical or memorial.

The Hirshhorn show gave shape to the contours of human destructiveness—the color, sound, shape, and emotions of the destruction itself as well as what’s being destroyed. In Fomon’s collection, the voice is similarly interested in forms of entropy. The principle tool is a verdant, wildly inventive vocabulary that seeks to name creation and its lyrically elusive but nonetheless inevitable inverse. Fomon speaks of thresholds, of gravity, of heavens; there are bodies of lovers, of forests and fields. There are questions of what constitutes the collateral damage of trying to create a life worth living? Of loving? Of writing a poem? What does love look like in language as it unravels? Like an exhibition on destruction, the damage is diverse in scale and abstraction. The language yearns for consolation, the ability to move through the world with an innocent, innocuous wake.

But this ideal is not imagined as possible, even from the very first poem, which begins: “And the energy / was spoken painted upon // the page. We changed our flocks / began to quiver.” When it ends, “The world would not look up / to feel the uncurling of skin,” we’ve been given a multidisciplinary creation, a language “spoken” but also “painted” upon the page, a sonic-visual entity naked in its early innocence that becomes bewildered by its inability to “recollect our heaven.”

The failure to recollect is central to the book. The poems frequently try to recreate and memorialize but find either falsity or outright emptiness within stanzas and artful white space. Even the two illustrations Fomon has included speak to linguistic and cosmic failure. The first—a simple diagram from a 1917 U.S. Patent of a collapsible revolving door—has specific parts labeled and paired with lines of a poem. The axle, “e”, is both “ distracted by distrust trussed in words” and “i transform for you means something.” Point “h,” the first and last points in the “poem” but also the far edges of the doors themselves, both read, “to think and think and think and think and think…” Endlessness itself may be innocuous, but eventually you have to exit in one direction or another. Fomon’s metaphor suggests one direction specifically: inward collapse.

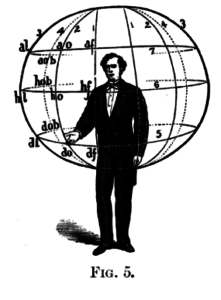

The second illustration, from Albert Bacon’s “A Manual of Gesture” (1875), shows a man standing with a spherical structure overlaying his upper half, complete with latitudinal and longitudinal lines and points at specific locations on the sphere. Those points, paired with the accompanying poem’s lines, evoke the articulate mapping of disintegration. Titled “What we have shown here, our bodies sodden:,” the first line reads, “thick hosts of imagery, manic spasms of constellation”. Indeed, the illustration does seem to portray a man presented with a maddening array of possibilities; letters and numbers and lines arranged around the sphere recalling the circular, but whole, plane of existence within the revolving door. Like the revolving door, however, and its eventual collapse or exit, the sphere’s stasis is only an illusion. The last four lines of the poem rupture that inaction: “l. our actions before us, our chart of consequence / ho. repeat i think i might be dying / af. i felt the world wobble before me 6. splitting us into you and me”.

Earlier, this split, perhaps not yet completed, contains hope, as when Fomon writes, “I in my we am beginning to sculpt / a certain love in experience.” Or the following lines, which over a wide scope of possibility:

Listen. Form the oceans under nails. Form the dirt

from perfect resonance.

Listen to the thundering infinity

the eve we said no more.Blued and rifling my mouth

waiting for a song to appear.

If only saying nothing, or waiting, or reveling forever in the moment were possible. But the lyrical lushness of Though We Bled Meticulously articulates the failure of trying to say nothing, as well as the sheer gravitational force of continuing to try to articulate nothing’s opposite—to create a universe populated with a love whose passage through time doesn’t result in its eventual destruction.

Fomon locates that universe in memory, the contours of which promise lasting, meaningful stasis, that preserved “heaven,” as when he writes, “Our art has manifested in the bronze statues we have mirrored of ourselves.” Like our own universe, however, what those memories contain is also subject to gravity, of movement, of a trajectory that promises only change in the form of destruction. What can a poet do but map this journey? To press pause and sketch the parts in motion is to look for cracks in the elegant machine, for possibilities of delaying the inevitable, coloring sadness different shades of hope.

Fomon isn’t offering solutions, but perhaps an ambitious, more accurate map of loving and longing. And like the videos of a vase being shattered or an apartment being trashed and then reversed, the art of the map is a force itself. And so we have lines like “I spent the morning smitten, / awed in crackling melt”, and “I became a night of tortured footmen / their feet curled into moons.” In these lines, as throughout Though We Bled Meticulously, the vocabulary is always on the edge of meaning, reaching towards some preserved memory of when love was whole.

Torin Jensen is a poet and translator living in Denver. His poetry and translations have appeared in numerous journals including The Volta, Asymptote, Radioactive Moat, Circumference, and the Harriet Foundation Poetry Blog, and he’s the author of Phase-sponge [ ] the keep (Solar Luxuriance, 2014). His criticism has appeared in One Good Eye, Yes Poetry, and Entropy and he’s the co-editor of Goodmorning Menagerie, a chapbook press for experimental poetry and translation.