Sin inglés, sin amigos, sin madre: a micro-memoir

Previous

Next

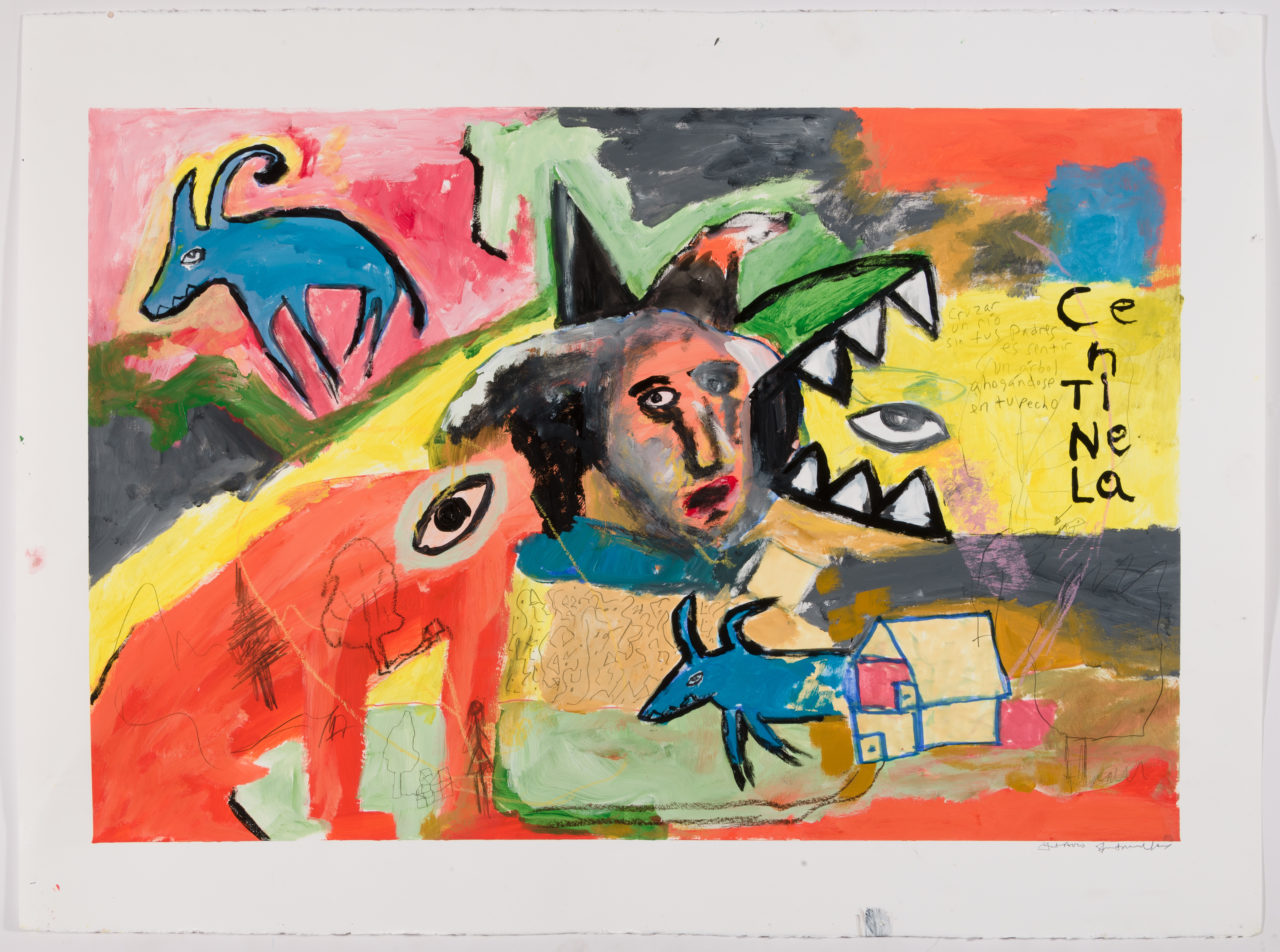

Author’s Introduction

What happens when you are nine years old and you are separated from your parents? You become a writer.

You scribble on the margins of notebooks, and often all you write is, “I miss you,” but in Spanish, the language in which you were first loved.

Or maybe you write your mother’s name, ‘amá, nothing more than that.

Because a contraction is a visual form of separation: mamá. No one will read what you write.

You smear the letters with the heat of your fingertips.

True, you were a tad older than some of the kids separated by 45’s “zero tolerance” policy. And yes, in your case, your parents gave consent, heartbreak in their throats.

But still, you were young enough to not have a say and old enough for the American Dream to call on you.

It promised you books.

Promised you a better life than what you would have lived in Mexico.

Back then, everyone you knew believed this.

El norte, where one can sweep dollars off the street,

own a washer and dryer.

A TV.

That’s how much abundance there is.

Better cross the line than poverty,

better cross the line than stepping on the threatening shadows of gangs and state violence. Don’t all parents want the best for their children?

As a writer you keep making the crossing—but now you journey south of the Rio Grande. You want to find your first language, your parents as you left them, the same dirt patio where you walked shirtless and barefoot.

What you really want is to find the life that you could have only lived in Spanish. The one you lived for nine years and that English, your second language, fails to truly name.

You lost everything.

And everything has no concrete name. No proper name. Everything doesn’t have a country, a playground, a domicile.

Does it ever?

You are an exile forever.

Its essential sadness can never be surmounted, proclaims Edward Said.

Maybe he is right,

and maybe you are, too.

And this is why you write,

because even if you own a house, you have no home.

Because even if you own a dresser for your clothes, an invisible suitcase always waits for you by the door, full of the invisible things that you will carry with you.

Where are you going?

Not sure you even know, but your uprooting doesn’t let you forget that you have no true ground to stand on.

Half of you is invested in the poem’s next line, and half of you is always waiting for goodbyes. This is what your being is composed of.

Two languages with two different lexicons bordered by one constant: loss.

English is never enough.

Spanish is never enough.

Language is never enough, and yet, it is the only home you truly know. The only country where you can be a stranger and still be welcomed.

And you keep searching for it, reaching for it, like the first time you rode a bus from a small town in Tamaulipas to a small town in the Rio Grande Valley, to the place where toddlers are now held, have been held, in “tender age” detention centers.

See their wide-open mouths crying for their mothers,

some so young they can’t imagine the word mother.

How many of them must have tried to say no te vayas in English?

How many of them will write their trauma on the margins of notebooks?

What role will language play in their lives as they try to articulate their sense of displacement in the world? Their incessant sense of dislocation?

How many of them will simply not remember?

And yet, you can’t really say how a separation of this magnitude will affect these children in the course of their lives.

You can only speak for yourself.

And this is what you are doing here, on this page, telling the world that you haven’t forgotten, and that your whole life has been a quest to find the right words to say, I remember.

Remember.

Because that first time you stepped on a bus that would drive you hundreds of miles north away from your parents, your brother was with you.

He was eight.

And both of you stood on the aisle of that crowded bus, looking out the half-open window, watching your mother in tears, her body not waving goodbye.

What for?

If she had, half the sky would have been erased by her hand.

—

Octavio Quintanilla is the author of the poetry collection, If I Go Missing (Slough Press, 2014) and served as the 2018-2020 Poet Laureate of San Antonio, TX. His poetry, fiction, translations, and photography have appeared, or are forthcoming, in journals such as Salamander, Texas Highways, RHINO, Alaska Quarterly Review, Pilgrimage, Green Mountains Review, Southwestern American Literature, The Texas Observer, Existere: A Journal of Art & Literature, and elsewhere. Visual poems have been exhibited in several galleries, including Presa House Gallery, Equinox Gallery, and at the Southwest School of Art in San Antonio, TX. He holds a PhD from the University of North Texas and is the regional editor for Texas Books in Review and poetry editor for The Journal of Latina Critical Feminism & for Voices de la Luna: A Quarterly Literature & Arts Magazine. Octavio teaches Literature and Creative Writing in the M.A./M.F.A. program at Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas. @writeroctavioquintanilla | octavioquintanilla.com