Nomi Stone: “the air we scull” – Phil Metres’ Sand Opera

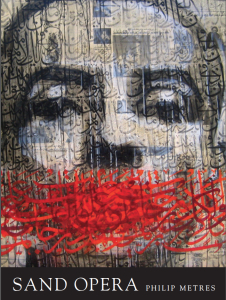

Sand Opera

Sand Opera

Phil Metres

Alice James Books, 2015

In Phil Metres’ Sand Opera, we are asked to activate the ear in a plea against the eye. Loosely structured like an opera, successive sections of arias and recitatives act as hitherto unheard cries of captured Arabs and Muslims, interspersed with blues ballads in the voices of American soldiers. Indeed, Metres begins the book with two epigrams about the perils and seductions of vision: the first from Michael Herr’s Dispatches, and how its lacerating images “just stayed there in your eyes”; and the second, a query from Corinthians: “If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be?” As an opening wager, the first poem in the manuscript, “The Illumination of the Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew,” enacts our visual consumption of that skewered flesh: “skin from limb/ their eyes// narrowing knives/ he balances.” The duration of the book acts as a rebuttal against such consumption, re-attuning us instead to the body’s cry and finding a lullaby in its wake. Metres’ resulting Opera is a carved shard, extracted via erasure out the concealed violence of the military term “Standard Operating Procedure.”

In an opera, the arias act as heightened individual reflections, in contrast to the recitatives, which further the plot. In the first section of the book, “the abu ghraib arias,” Metres deploys intertextuality and erasure, asking us to confront the dismantling of the human being through interrogation and torture. Calling the section a “dialogue between Standard Operating Procedure for Camp Delta at Guantanamo Bay, the soldiers who served in Abu Ghraib, and the Abu Ghraib prisoners,” he culls from military manuals, testimony of victims, official reports on the scandal, interviews, the Bible, and the Code of Hammurabi. Through that collage, Metres heightens the tension between the physicality of the harmed body and the image of that body, one of the themes that haunts the book. In that gap, we are asked to consider how a body is named — a naming that creates or undoes life. The fourth poem in that sequence “(echo/ex/)” is exemplary version of the work Metres accomplishes in many of the adjacent poems.

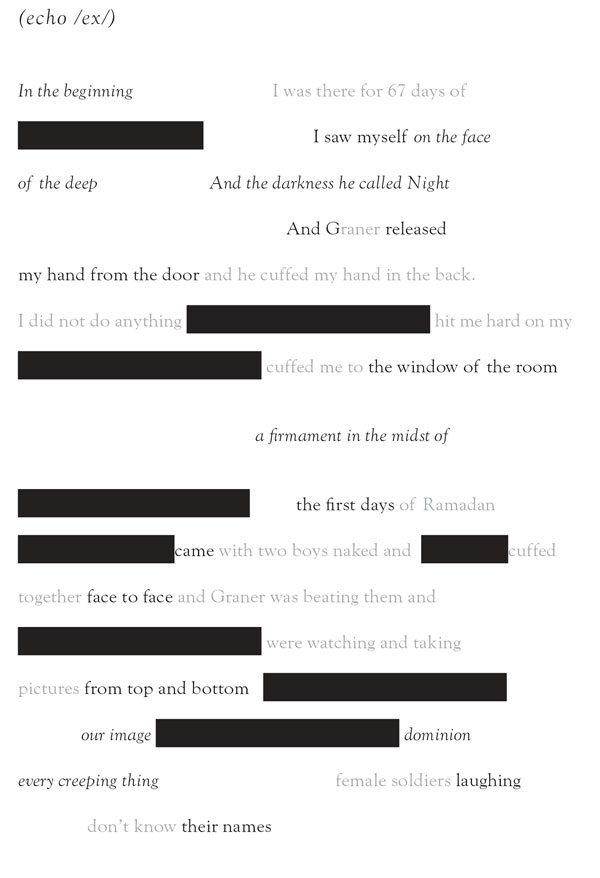

In the first movement of the poem, Metres interlaces language from Genesis with the testimony of an Abu Ghraib prisoner, generating the terms for the prisoner’s dissolution. The poem starts with the opening of the Bible: “In the beginning,” followed immediately by the words of a prisoner, in muted, gray type-font: “I was there for 67 days of ”, which is truncated by a block of redacted text—an unspeaking of the act. In a reversal of creation ex-nihilo, via the word of God, the poem undoes its initial premise, locating us instead within an unmaking. In the following line, this dark wager is continued, with another line from Genesis, as the speaker sees himself “on the face/ of the deep And the darkness he called Night.” Metres positions us here uneasily in this clamor of voices. Is the speaker the perpetrator, claimed into that deep by the dark hour of his deed? Or is the speaker the undone one, unspoken back into divine constituent syllables in the dark? This ambiguity makes us complicit, unable to stabilize the harmed body’s migration through that void.

In the following turn in the poem, testimonies again make an uneasy accordion around a verse of Genesis, as the prisoner struggles to retain the integrity of his body. For the first and only time in the book, the perpetrator, Graner, emerges by name, thereafter referred to only as “G.” G roughly handles the body of the prisoner: “and he cuffed my hand in the back./ I did not do anything [erasure] hit me hard on my [erasure] cuffed me to the window of the room/ a firmament in the midst of [erasure].” The prisoner’s body, without a reference point of its own, is a done-to, shaped around the erased acts. Still, momentarily, it holds its own contours again, finding a “firmament” through the portal of the window. The body is reconstituted through the knowledge of the continuance of the world outside this room. Indeed, in a later poem in the book, a spatialization of an interrogation room, the presence of a fly in the room becomes the body of the outside, bringing the prisoner joy, only to then become another body stifled by the room’s containment.

In the final turn in the poem, through the continued interweaving of polyphony and erasure, Metres offers a damning critique: he shows how the violated body of the prisoner is supplanted by a picture of that body. In a dark twist on the procreative parable of Genesis, we are instead offered a disassembly: “came with two boys naked and [erasure] cuffed/ together face to face and Graner was beating them and/ [erasure] were watching and taking/ pictures from top to bottom [erasure].” In Genesis, when the two beloveds turn “face to face”, their union becomes perfect and restores the world. Here, to the contrary, the conjoined and harmed flesh of the two prisoners becomes a razing of that world. We are meant to understand here perhaps, that such dismantling is burned in most permanently through the eye: through the act “watching/ and taking pictures.” Metres then uses further biblical imagery to transform that picture into a burning into a collective human consciousness: “our image [erasure] dominion/ every creeping thing female soldiers laughing/ don’t know their names.” The author culls from a verse in Genesis where God proclaims that man will be made in his own image, and will thereby be his arm on the earth —extending dominion over all living on the planet. Yet Metres reconfigures the verse: the image here is, rather, of man broken by man — a testament to a larger human brokenness. The divine prophecy of human sovereignty is twisted too: human dominion becomes the unmaking, the unnaming of the other. The image (and the harsh laugh at its center) cascades through the space of the poem, insisting that we deflect it. There are bodies here. Those bodies have names.

Perhaps the most remarkable section of Sand Opera is the third section of the book, “Hung Lyres,” which comes after these extended sections of fragmentation and erasure. In the section, Metres masterfully uses sound to create a child’s ear and the ache of the accruing imprint on its drum. The lyricism and tenderness of the section do not simply offer us a reprieve; the whorl of the child’s ear constitutes in the collection hope. The third to last poem, “@”, is emblematic of the sequence as a whole. Throughout the couplets of the poem, there is a sonic rippling that insinuates the issuing and reception of sound in the developing ear. In the second line of the first couplet, we are given “curves, their riverine curves”— whereby the issued word is echoed and elaborated. Yet by the second couplet, we are presented with the “auricle” and rejoined with its near match in the third couplet: “oracle.” The delicate instrument of the becoming-ear tries to measure the tiniest distinction between sounds; it tries too to therein make meaning. The auricle is a structure of the ear as well as another word for the atrium of the heart; in this context, they are both “oracles.” To be attentive to the ear is to be attentive to the forward pulse of the heart. Still, entering the world is fraught: the possibility for mishearing, for misunderstanding, is ever-present.

Metres deploys successive sound-patterns that evolve over sections of the poem, which we might read as following the ear’s development. The work of sound in the poem is gentle and unfolding and never overbearing. In the first several couplets, he relies on the heat and enclosure of “OO” sounds, conjuring the hollow of the ear. He uses here the words “blazon,” “auricle,” “bloom”, “trumpet,” “oracle,” and drum.” We are in the realm of the deep canal of the ear, perhaps as it is developing in the womb. In the next phase, he uses the uncurling of “L” sounds: “lobed,” “cymballed,” “canal,” “vestibule,” “elliptical” and “circular”— the ear’s outward whorl as it interfaces with the world and receives its first inputs. Indeed, just before this sonic turn, the speaker of the poem describes the first startling imprint on the ear. In a single italicized line that ruptures the couplets, the fifth line of the poem, we are asked, the child’s voice: “what does it mean, amputee?” The child has learned that there are bodies that are severed in the world. After this knowledge, the ear — the heart — will not be the same.

In the tenth line there is another such interjection into the child’s knowing: “is there such a thing as “orphan”? The child now lives in a world where a child might be alone. At this moment of imprint, the speaker tell us: “& we host a motion labyrinth, a squid./Maleus, incus, stapes.” That is, the world and its promise of loss wriggles in: there, into the successive compartments of the ear. Bearing this knowledge, the speaker nonetheless implores: “Cover your ears// dear child, your cartilage is not yet hard—/its too soon to know to hear is to bend.” Following this moment of pure tenderness and protection, Metres turns to “S” sounds: “Your silk purses will sow the wind./ Your flexible shells haul their own ocean.” These S’s, their exquisite gentleness, would almost seal for a moment the child’s ear shut. But instead, these susurrations imply a soft permeability to the world. The ear “sows the wind”— an active scattering upon the earth of its rhythms. Furthermore, the shells of the ear “haul their own oceans.” That is, as Metres writes in an adjacent poem: “the listening tuned inward.” The child is whole, containing her own ocean. If she listens there first, she will be made stronger for the imprints that come.

The next poem in the sequence is a meditation only made possible by the created ear. The child asks, upon hearing wailing: “is that man crying/ or singing.” In an astonishing metaphor, Metres makes the man’s body itself into a conduit for war’s terrible music: “War takes him in its fingers,/ raises his body a punctured bone// flute, to its lips, and breathes/ the living dust/ to dust alone”. Metres is not aestheticizing violence here by making that cry sonorous. That dark music disperses the beloved, played body, turning it into “living dust.” That dust is our own inheritance: we cannot but breathe it: “this is the air we scull/ air of ancestors & ashpits”, and we bear every responsibility to it. The child has been listening this entire time. Her listening has turned into pathos and care, into recognition of the other — and a refusal of the dangerous slippages in language and thought that allow us to subsume the other: “she corrects the voices// she hears butcher/ the name of the country she’s never//seen—it’s “ear-rock,”/ not “eye-rack.”

—

Nomi Stone is the author of the poetry collection Stranger’s Notebook (TriQuarterly, 2008), an MFA Candidate in Poetry at Warren Wilson College and a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at Columbia University. She earned a Masters in Modern Middle Eastern Studies from Oxford and was a Creative Writing Fulbright scholar in Tunisia. Her poems appear or are forthcoming in Poetry Northwest, Memorious, Plume, Drunken Boat, and elsewhere. She is currently working on Kill Class, a collection of poems based on two years of fieldwork within combat simulations in mock Middle Eastern villages erected by the US military across America.