Lips that Kissed Lips

by Erich Slimak | Contributing Writer

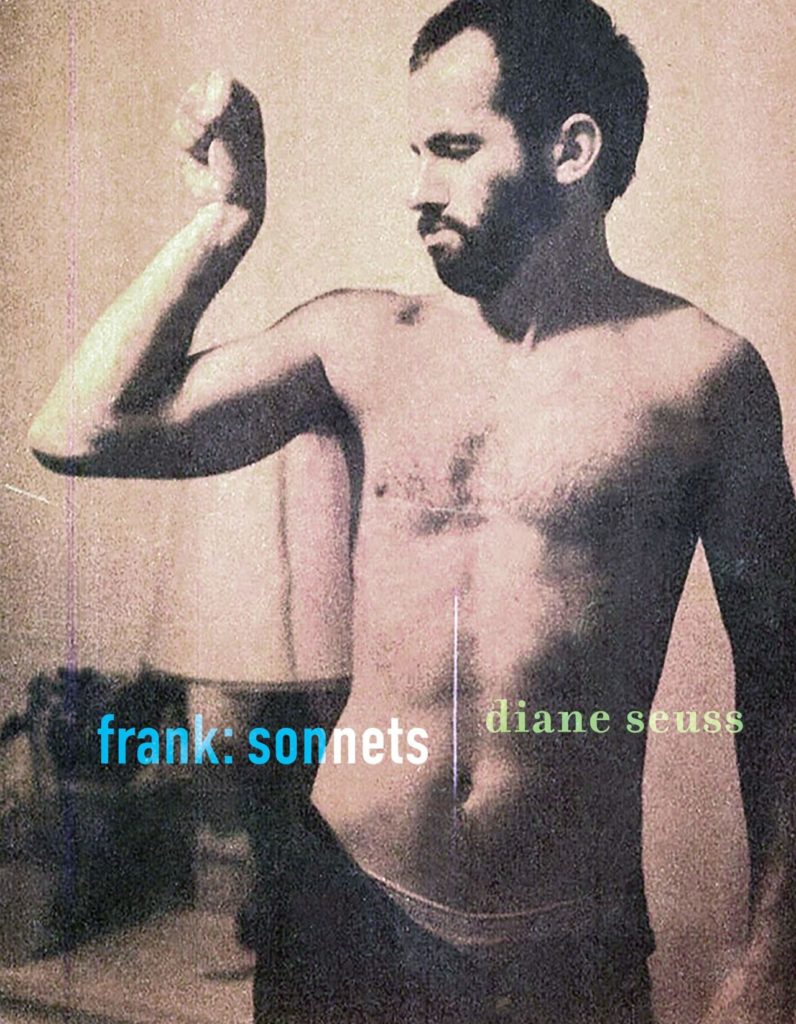

frank: sonnets

Diane Seuss

Graywolf Press, 2021

The sonnet’s history is long and varied. Its origins, of course, are in courtly lovesickness—think the beloved illumined by a single beam of moonlight letting her hair down in a garden—but when the sonnet was imported from Frederick II’s Sicily to England, the form’s range became apparent, moving beyond romantic frustration privately expressed into the more public multidimensional form we find in the work of Shakespeare and Milton. In five-hundred odd years, poets have expanded the sonnet’s thematic reach further still. Using its requisite volta as a catalyst for transformation, larger questions about identity and social change have equalled or superseded romance in the sonnet, resulting in the contemporary American sonnet, a denser, more muscular form as seen in Terrance Hayes’ and Wanda Coleman’s remarkable work.

Lucky for us that Diane Seuss, one of our most singular poets, has decided to take up the form’s mantle. In frank: sonnets, Seuss walks a tightrope between polite and profane to delightful effect. Unruly as ever, she eschews many of the sonnet’s usual conventions, employing only the occasional rhythmic or metrical twist, packing her fourteen lines as full of detail and observation as possible. Seuss’s sonnets use the form as a lens through which to observe the upheavals of human existence. At a sizable 152 pages, frank weaves in and out of a clear progression from the speaker’s childhood to her current life as a mature artist. As Seuss guides us through the timeline of her life, she consistently doubles back to the present; in doing so she establishes a home base from which she looks back at what she has experienced and lost. frank is highly self-conscious about its chosen form and that form’s conventions. In the book’s first poem, the speaker asks “how do I explain / this restless search for beauty or relief?” kicking off a search for an elusive poetic identity that characterizes much of the work in the book.

Over the centuries, as the sonnet’s influence and ambition evolved, so too did its preoccupation with unrequited love, moving from the specificity of Petrarch’s longings for Laura into a more abstract, diffuse, even metaphysical longing, a reaching towards something that cannot not be physically grasped, as in the work of John Donne or Gerard Manley Hopkins. Seuss channels this evolution winningly, engaging with different kinds of frustrated love (“After forty years of forced estrangement soul mate shows up”), occasionally consummating it (…loneliness I once lusted for I have become”) before branching out into something broader, connecting her longing with a desire to communicate and a frustration with poetry at large: “I’m stuck in this prison made of paper and ink.”

Later, Seuss responds to this quandary, writing “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without . . . is a good teacher.” In the book’s second half, the speaker’s declaration that “All things now remind me of what love used to be” acts as a subtle volta after which the work turns to embrace the form’s traditional romantic concerns. This shift mirrors the speaker’s stage in life, her own volta, from a rebellious young adulthood into a middle age that grants perspective and understanding, though the speaker’s voice is so raw and her divulgements so earnest, you can blink and miss the formal tip of the hat.

Seuss establishes an early tonal foundation via musings on death and beauty (“. . . the sunset, oh, ragged and bloody as a piece / of raw meat in the jaws of some big golden carnivore”) interspersed with meditations on the craft of poetry (“the only father, landscape, moon, food, the bowl”). However, the source of the book’s early heat is its engagement with the speaker’s childhood, her “looking for salvation” amid a household gutted by the death of a father. The verse in the first movement shines, building a rural world marked by singular detail and characters: a dead man’s Aqua Velva, grotesque farm animals, suitors “like carrion / birds” howling for the speaker’s mother. These all cohere to create something of a dark pastoral, a world that gestures toward the trappings of an anti-paradise through symbols typically elevated in the sonnet form. This early universe is suffused with a double longing—the juvenile and the mature speaker looking forward and backward, respectively—and is populated as vividly as a front lawn full of detritus in the wake of a flood.

From there, the book grows wilder yet, offering a litany of adulthood’s dissipations and wrenching losses. These poems begin with the punk rock grime of 1970s New York: “Parties among strangers . . . Quaaludes between my lips . . . I was the new thing. Then just a thing.” The speaker’s dear friend, the artist Mikel Lindzy, dies of AIDS, and her son struggles with drug addiction, something she blames herself for. “I’d authored him in my bones,” she muses, “I forged / his suffering, his nail, his needle, his thrill.” frank’s trajectory bobs and weaves in a typically Seussian manner, juggling an incredible amount of detail while remaining grounded in the text’s emotional cornerstones: loss and the developmental trajectory of identity.

As its subject matter evolves, so does frank’s relationship to poetry itself. The adult speaker, examining her more formative years, first reaches towards the concrete, unsavory realities of the writing world (“The famous poets came for us, they came on us or some of us / at least on some of us they did not come”), details and images to which she holds tight as she navigates the tidal shifts of her own identity. Ultimately, the speaker’s engagement with poetry evolves into a rigorous exploration of the craft itself, its joys and limitations. With age, the speaker’s experience of art changes from something she wants to happen to her and into a tool she uses to create her own sense of self. “Six lines and sick / already of this allegory,” she says. “Looking for a nonfussy definition / of the Sublime. Something I can really sink my teeth into.”

The restrictions of the sonnet make it a natural vehicle for frank’s progression on both the micro and macro levels, owing to the form’s endemic sense of longing and its volta pivoting towards new knowledge or catharsis. The form’s constraints allow the collection as a whole to look backward while never compromising its forward-facing momentum towards self-possession, maintaining this duality of vision long past the book’s depiction of childhood. As frank circles back to the present tense in its later movements, it is defined by a sense of solemn disenchantment at what the speaker has found to be life’s “peasantry and pain.” Even from this traditional vantage point, longing for a lost past rather than a hoped-for future, Seuss refuses to settle for static, dreamy melancholia that might find a home in a “typical” sonnet. In the book’s last poems, her images seem to reach for morbid extremes: “my dad’s body lost to us . . . / found again, we set him in Dickinson’s coffin.” To its very last poem, even as it looks death right in the face, frank embraces movement (“he kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed Whitman’s / lips”). Seuss never gives up on the book’s double vision, the idea that a sonnet can act as an engine for transformation as well as a location: somewhere to mourn as well as to grow.

By virtue of its sheer length and scope, the collection contains inevitable uneven stretches. Even accounting for the breaks such a project must take from its bursts of thematic heavy lifting, some of the poems feel particularly out of left field. One example involves a dishwasher, the speaker “changed” and “incredulous” at the convenience of the appliance, though even this poem manages to rope in Keats, “opening / his eyes once again to dying.” On the whole, frank’s ambition is so vast and Seuss’s own interests so omnivorous that you can hardly blame her for a few odd ducks out of 128 sonnets. Most importantly, you can’t say that even the book’s weakest poem isn’t entertaining. The collection is a formally daring, kaleidoscopic view of personal history which bucks tradition while also bumming it a cigarette.

—

Erich Slimak is a singer, amateur basketball historian, and poet based in New York City, where he lives with his partner, their eggplant-shaped cat, and 8 million roommates. He received his MFA in Poetry Writing from The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he also served as Assistant Poetry Editor of Ninth Letter. His work has appeared or is forthcoming from I-70 Review, The Spectacle, The Pinch, and elsewhere.

Diane Seuss was born in Indiana and raised in Michigan. She earned a BA from Kalamazoo College and an MSW from Western Michigan University. Seuss is the author of the poetry collections Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl (2018); Four-Legged Girl (2015), finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open (2010), winner of the 2009 Juniper Prize for Poetry; and It Blows You Hollow (1998). Her work has appeared in Poetry, the Georgia Review, Brevity, Able Muse, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and the Missouri Review, as well as The Best American Poetry 2014. She was the MacLean Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Department of English at Colorado College in 2012, and she has taught at Kalamazoo College since 1988.