Liberty Through Diction

by Samar Abulhassan | Contributing Writer

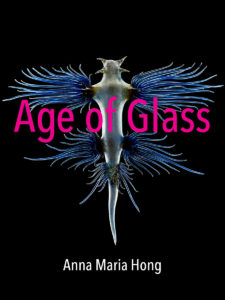

Age of Glass

Age of Glass

Anna Maria Hong

CSU Poetry Center, 2018

I carry Anna Maria Hong’s Age of Glass with me in my backpack for weeks, the book snug beside piles of poems written by children in the elementary schools I visit each week as a teaching artist, poems written to animals, poems asking for transport and friendship. I crack the book open, over and over, as if an oracle, for a brush of technicolor travel. “Glass is sand is time falling loose,” Hong writes in “The Glass Age,” and I feel myself simultaneously erased and revived, invited to be vividly present.

I shuttle from room to room during my work week, entering classrooms full of young writers who are at turns rambunctious, willing, delighted, or bored. Imagine a portable dance floor, where a tap dancer jubilantly creates endless combinations that jangle, crack, and cackle together. In Age of Glass, Hong’s re-cast sonnets provide their own rooms of possibility, rooms that bend, stretch, collapse, wink, and breathe. “I tried to hide again / but the veil was gone, so down I sallied / through dip and valley green with invitation,” she writes in “The Hologynic,” one of many poems that finds freedom in shuttling through time, where the body opens to embrace more of the world. “I was ferociously happy,” she later offers exuberantly.

The first poem I ever memorized was William Blake’s “Tyger.” At 11, I barely understood the questions posed in the poem, yet I marveled at the animal’s “fearful symmetry” and magnificence. The poem presented a kind of mysterious sound that stayed with me. Similarly, Hong dazzles with her sonic range within the familiar womb of the sonnet, shuttling among bits of fable, myth, dream, and global news fragments. In Age of Glass, word play and bursts of alliterative verse are similar agents of liberation. You can almost hear what seem like interceptions in Hong’s writing process, as if one eye-ear is leaning toward the unseen, while other allows the material world to permeate the poem. As she writes, in “Zone Planning, “Arrived and a riven, sans belongings or / partisan leanings.” Or in another poem, “A Parable,” words such as “muesli,” “embassy,” “fallacy” and “flimsy” co-mingle.

In the poem “Neptune Frost,” Hong writes: “I have tasted smoke angels on the tip / of oblivion. The angels turned me / like a face and gave me a new name, turned / my face like revolution. The moon swung free.” She later continues, “while I wrestled / my nature in the clearing, and a nation / burned like ice on revolving tongues, / turning like a stone where the red moon hung.” The poem invites language that shifts from bruise to burn to blue-black cold. The mind’s shifting temperature is graphed in many of Hong’s poems. It reminds me of rapidly wringing out my arms in a movement class, kicking off dust, shuddering, starting again.

Leaf through Hong’s collection, and you’ll find nearly all of the poems are recognizable as sonnets. Diversion from the form occurs primarily in Hong’s incredibly deft, acrobatic turns, though a handful of poems here rebel further, offering sudden indents and breathy white space. Against so many “recognizable” sonnets, the bursts of occasional white space give the impression of a suspended mind. One such poem, “I, Lyric,” feels like eavesdropping, “gripping as if that manic jabber were / good-looking / flat morning on window / façade / the split world catching radial pool.” Hong splits, spits, and splinters words and worlds open. “Give me liberty through diction / and fiction refined as sugar and oil— / product and process, again, again. / Who gains? What gives? / The sum of my positions, poisons, margins, intentions / to be home free—” reads “I, Tonic,” one of Hong’s tipsy yet restrained, endlessly playful sonnets.

Hong is not afraid to take her language experiments on a tightrope, then pull back at the last second, or just rest there, teetering, and wide-eyed. Her declarations are humble and full of self-erasure, while being exuberant and gallant. “I was erased as a morning face / and slim as a pocket. I was steady / as dust and feathers blown hard across / a mackerel lake. I was bloody / chuffed in three-quarters, but I wasn’t empty / anymore. I was tone, pause, energy,” she writes in “Aura,” which concludes, “No, I did not enjoy / ‘the process’ of effacement, though it was a start.” Yes, the page offers a home to the poet, through bursts of knowing, alliterative verse, riddles, and trust falls. But don’t get too comfortable. As she ends “The Black Box”: “A rise / lets breath bait breath. The work arrives, reverses.”

In “I, Sing,” Hong limits herself to only a few words, embracing the ampersand like an incantation. She begins, “out of this world and out of time & out / of love & out of mind,” which morphs me into a spinning desk globe, and when we land upon the only uppercase word in the poem, “Damascus,” we are reminded of the gravity of disaster. We’re dazed and altered as shamans, “out of courtesy / & out of shock & out of duty / & out of turn & out of tune & out of line.”

In her notes to the collection, Hong names some of the glass works that informed the poems in her collection. The delicate, astonishing music of glass is an ever-present muse. “I am a cone on quartered tendrils, deaf / as an epitaph. Art is dead, but sponge / will take forever. I’m the holy stuff, the nod blown up inside your head.” Reading this, I imagine the basement shop of a master glassmith, who uses air and flame to fashion a creature, plant or vision. The glow of a glassblower’s workstation permeates the desk of a poet in Age of Glass, and I was parked on a bench of Hong’s mind, lucky listener to dancing flames of her visions and voice.

—

Samar Abulhassan holds an M.F.A. from Colorado State University and worked in California public schools for seven years. Born to Lebanese immigrants and raised with multiple languages, she is a 2006 Hedgebrook alum and the author of two chapbooks, Farah and Nocturnal Temple.