The Legacy Suite: Field of Yellow, Field of Knowing

The Legacy Suite is a three-part interview series in which poets delve into the journey of publishing a debut full-length collection: before publication, during, and after. For the revival of this interview series, I.S. Jones speaks at length with Detroit-based poet and educator Brittany Rogers about her artistic influences and the process of writing, rewriting, and placing her debut. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Somewhere in Detroit, beauty is happening. Somewhere, in this corner of the Midwest, a young girl touches her girlhood for the first time the way a deer touches an asphalt road before crossing. A young girl comes into a knowledge that marks the body before language fully forms. The body stores memory in its muscles, its sinew, skin, and eyes.

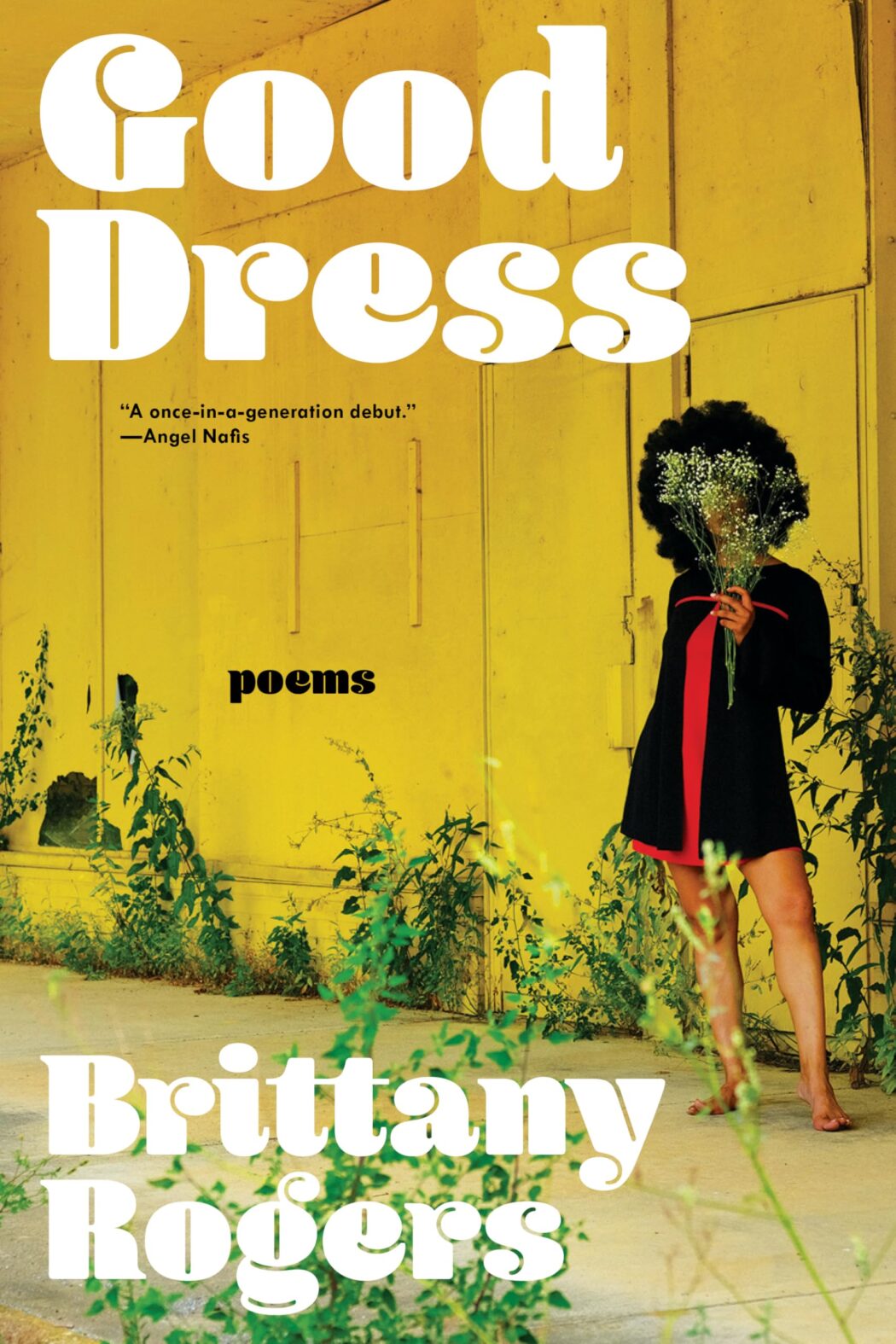

These binding strands—Black girlhood, motherhood, and womanhood—are the governing principles of Brittany Rogers’s debut collection. In Good Dress (Tin House, October 2024), Rogers’s personal transformation is underscored by the socio-politics of place, of that crucial (and often fraught) moment in adolescence which finds a young woman teetering between childhood and adulthood, in need of financial security to thrive. What does it mean to want, to desire nice things, when you have been told poverty will not allow you softness and ease? Rogers’s work, unflinching in its precision, confronts and refuses a simple answer to this question.

I.S. Jones (ISJ): The cover of your book is an image from the poet and photographer, Rachel Eliza Griffiths. You situate much of this book between Black girlhood and Black womanhood, especially motherhood. I’m curious how this image best spoke to what Good Dress desires to translate to its readers and how critical it is to have artwork specifically by another Black woman on the cover.

Brittany Rogers (BR): So much of my book thinks about audacity and what audacity means to me as a Black queer from Detroit, its own state of audacity. Also, my book thinks about landscape in a very industrial way. That image marries both—the bright yellow, the red, the barefoot Rachel Eliza with the flowers. The beauty of the landscape is palpable to me. Also, how much of that landscape was industrial and sparse and bare. That audacious image embodies what I want people to feel when they read Good Dress.

ISJ: That’s gorgeous. I love that, especially because I imagine usually when folks think of Detroit, they probably don’t think of a bright yellow. With the cover, a little bit of red and black pop against the soft green too. For me, as someone who’s lived in the Midwest for a little while, those colors make sense against what the landscape offers up. Outside this region, I imagine that when folks think of Detroit, they think of the color gray. Detroit has such a vast and complex history, racially, socially, and politically. Who else but someone native to the city can best speak to its complexities regarding its color palette, so to speak. In Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, the nighttime serves as a character of its own. Good Dress joins this tradition, featuring Detroit as a character, as a foreground, and as a texture which we, the readers, have the privilege to have rendered through your eyes—you, the writer. I’m thinking about the poems, “Detroit Public Library, Chandler Park branch, erotic fiction section,” “Doing Too Much,” and “Detroit Pastoral.” Notably, in “Detroit Pastoral,” the speaker is adept at remarking on the city’s beauty without shying away from how fraught the living conditions can be.

“This block gap-toothed,

fickle. Fields of yellow grass.

Field of soiled Pampers and beer bottles.

Food desert,

but they graze anyhow.”

Detroit stands as a portal to the past, but also perhaps a glimpse into the future. I’m curious, why was it critical for you to offer such a robust and complex view of this Midwestern city?

BR: Thank you. This is such a generous question. Yes, I absolutely think of Detroit as a character. It’s so big that it is its own person. It’s a really hard space to contain. When I was first writing Good Dress, I wasn’t writing about Detroit as much. I think I was trying to stay away from including the city. At some point, it became kind of impossible. Being a Detroit girl has formed so much of my identity and it’s such a part of who I am that I think it was inevitable Detroit would be like a character in this book. It’s really important to me to always talk about Detroit in a way that’s layered and in a way that offers Detroit autonomy. Growing up, something that was always so frustrating was the way that people talked about Detroit.

ISJ: Coming from folks who aren’t from the city proper, I imagine.

BR: Yes, always from people who aren’t from Detroit. Always. People talk a lot about crime. People talk a lot about lack and poverty. People talk a lot about blight in the city and how many abandoned homes we have. Even now, there’s a narrative about the city making a “comeback,” when really it’s being gentrified. It’s an anti-Black narrative that people pretend is not anti-Black, but it can’t not be when Detroit is (approximately) 78% Black per capita. Up until the last census, we literally were the Blackest city in America per capita. It means something significant to me to be from here.

My experience is completely shaped by the fact that I could count the number of White people at my high school, and I went to a school that had 2,600 students. That does a very specific thing for the type of grounding of a person. When I went to college, that was my first time seeing so many White people in social settings. I went to a school that was about 45 minutes away from home. That school was considered very diverse, with what most would consider a large population of Black students, but it just wasn’t home. Detroit has always been a space that has layers, that has a lot of culture, a lot of narrative. I felt like I would have been doing the city a disservice if I didn’t explore that narrative.

ISJ: Especially because Detroit is such a huge music hub. Some of the greatest this country has ever known, Detroit gave us the Supremes, J Dilla, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, the Temptations, and others. In Good Dress, Detroit as a voice of its own is amplified by virtue of what is so urgent to the speaker—this symbiotic relationship to lineage and music. Who are the artists, writers, thinkers, rappers, and the like that have been influences to you and your work? Obviously, we have Kash Doll and a lot of references to women rappers, not only in this book, but in your work as a whole.

BR: I’ll start with music. I’m very ingrained in hip hop, which most people familiar with my work know, so I’ll step outside of hip hop for a moment. Etta James, Nina Simone, and Aretha Franklin are my trifecta. The way that they approach craft, but also the emotion, the intention behind all of their songs, the uniqueness of their voices—I think there’s something singular about each of them. You can’t mistake them for anybody else. That deeply resonates with me. I write to their music all the time. I edit to rap, but I write to ballads. And I’m a sucker for a great ballad and a strong voice. In terms of writers, I love Saidiya Hartman’s work. I love her practice of witnessing. I love what she does with ethnography. She teaches me and reminds me all the time that we get to imagine, and we get to reframe, and we get to expand upon any notion or stereotype or hole that people may try to pigeon you in. I love the expansiveness in her work. I love Rachel Eliza’s work, specifically Seeing The Body and Mule & Pear. And Wanda Coleman, of course.

ISJ: Yes. Oh my god. I teach her every chance I get. Her poem “Off-Bonnet Sonnet” changed my life. Wanda Coleman is a huge influence. Mercurochrome and Bathwater Wine were so foundational when I was coming up as a poet.

BR: The collection, Heavy Daughter’s Blues, has my heart forever just for the frankness with which she approached the page and her ability to be honest, even for the way that people responded to her honesty. She’s a person I’m always going to cite.

ISJ: A poem of hers I teach every chance I get is “In That Other Fantasy Where We Live Forever.” She captures, for me at least, a girlhood that does not shy away from messiness and mistakes. There’s also a rebelliousness in her work, something that we rarely get to see portrayed by Black girls, which also segues me into my next question. So, there are different kinds of, not to be corny, ’hoods the book moves through—womanhood, motherhood, and girlhood. Girlhood, with its secret inner workings, is one of the strongest and most critical threads of the book. I’m thinking here of your poem “Hunting Hours” and the poem called “I lost my virginity / After making a pact to become women with my cousins.”

In Spells, I make parallels between deer and Black women as deer are traditionally a part of the game of venery and are the highest form of game. In researching deer, I was struck by how deer are valued most by what can be taken–their meat, the velvet of their antlers, their skin, their head to be mounted on a wall. Using deer as an extended metaphor for the way this world treats Black women, the question then, is what does it mean as a creature to come into the world twice endangered? I know your own work adopts some of these tropes as well. Deer imagery leaps in and out of this book and this second poem, which references the softest parts of Black girlhood that are often hunted for sport. I love that we, as Black women, are creating our own lineage with deer.

BR: That’s the goal. Of course, we should have our own voices, but I love this lineage, and I always hope that it’s clear who I am inspired by and who I may be in conversation with.

ISJ: When you’ve written these poems, how has talking about these “rites of passages” healed your inner child? Also, if you feel comfortable, I would love to hear about how “I lost my virginity / After making a pact to become women with my cousins” came together. The stylistic and very smart choice to have the poem quite literally bisected in two shows who the speaker was before they lost their virginity and who they were after.

BR: That poem was my first time, and I think only time, writing a contrapuntal. This experience, in some ways, very much split my life in two. I was told losing my virginity was significant, and it was the opposite: it was literally a game between me and my cousins. Even as a girl, as an adolescent, as a teen, I was not attached to the idea of my virginity. I was not attached to the idea of propriety. I was told when you lose your virginity, you’re going to fall in love, and then this will happen, and then that. None of this happened. I went home. It wasn’t even all that good. I went on about my business. That revelation was like a veil lifting for me. It reminded me that there are some things I know, right? As young as I was, there are things that I did know. Going back and writing those poems, that’s what it did most for me: it reminded me that I have always been who I am. There’s an intuitiveness, a knowing we have about ourselves that even when we can’t find the language for it, is still there. So, remembering some of those things, it was like, “Oh, you knew. You were hip. You were not wrong.”

ISJ: That is so apt and sharp. Also, to share, this was exactly how I felt, what I moved through, when I lost my virginity. I didn’t care about the boy I was dating. Actually, I lied to him to keep him from breaking up with me because he told me he was in love with me. And I told him, “Yeah, sure! Me too! So can we sex now…or …?” But I didn’t love him at all. I cared more about having the story than the actual act. I wanted to have a token into the tribe of girlhood, and I knew losing virginity was the way to that. It was more about having something to offer the other girls I wanted to be in tribe with than the actual act of itself. It was always about impressing other girls and showing them, “I’m cool too. I can hang too.” I think so deeply about those pacts and rites of passage that come with girlhood. Looking back, we might have all been deeply wounded by patriarchy. But, also, we were so desperate to impress each other. I want to zoom out to ask about the entire production of the book. When did you first start realizing you were in the middle of a book project? Had you deliberately set out to write a book, or you were writing poems when you realized you were in the middle of a collection? When did you understand that you had said and done everything you needed to?

BR: Around 2017, if I’m not mistaken, I was sending what eventually became Good Dress out as a chapbook. I went to VONA [Writers Workshop] and had an incredible, incredible experience, and studied with Willie Perdomo, who was amazing. The cohort that he picked that year was so special because we fell so in love with each other.

It was a really magical experience. Working with them, I think, helped me see, “I have a lot more to flesh out here.” So, I pulled it from submission, worked on it some more, and worked on it some more. At the time, I believe it was called What Runs in The Blood. And, actually, Itiola, we workshopped this together at The Watering Hole, with Jericho Brown. I want to say that was in 2019.

I started sending it out tentatively again, but by then, I had the feeling that I just wanted to rewrite the whole thing. Then, in 2020, I went into my master’s program at Randolph. Mind you, I had 50,000,000 things going on. This was the first year that we knew of COVID, and I was pregnant. I had a baby that September right in the middle of all of that.

That summer of 2020, I realized, “I don’t know that this is a project. I don’t think I’m invested in it the way that I was invested in it before.” Going back through the book, I felt really disconnected from a lot of the poems. The book as it was wasn’t saying what I wanted to say, so I realized I wanted to rewrite it. I was talking to my mentor, Philip B. Williams, who said, “Well, rewrite it.” I’m thinking, “But you make it sound so easy.”

ISJ: No. It’s not.

BR: That was probably the best solution. I looked through that book and pulled up the poems that I was most invested in, that had the most heat coming from them. Those poems then became Good Dress. The original collection was a lot more about motherhood. It was almost singularly about motherhood. By the time I got to Good Dress, I understood it was not the totality of who I am, and I didn’t want that to be the totality of my work. A big shift happened there. From 2020 on, I just wrote and wrote and wrote. I want to say, by the time I submitted it as my thesis, one of my thesis readers, Angel Nafis, said, “This is a book. Like, this is not a thesis project. This is a book.” I think that was so because I had really been writing towards Good Dress since 2017. Then I sat on it for a while, I didn’t look at it, didn’t touch it for another year. And then I worked with the poet and editor Kiki Nicole, who’s brilliant. If you ever get the chance to let them edit your work, you absolutely should. They did a lot, from looking over the book as a whole, to large edits, offering a lot of feedback and suggestions. Looking at a lot of what Nicole offered—the questions they asked about the manuscript—allowed me to see the connective threads happening in the manuscript that I could not yet see. That, I think, helped me do a last big haul making Good Dress what she is now. And then Tin House opens up once a year for poetry manuscripts in May. I slid the book in there and didn’t hear anything for a while. I’m thinking, you know, they must not have been interested, and I was anticipating a rejection at some point. I heard from them, I want to say, in the middle end of October. They said they wanted to see the whole manuscript. From there, things progressed really quickly, and that was all she wrote.

ISJ: I’m curious about, as much as you can disclose, your contract with Tin House. I’m curious if there was a right of first refusal clause in the contract. Also, in terms of marketing and production, do either you or the press have a concrete idea of how the book will live in the world? Where would you want your book to be marketed? And also, where would you want to go on tour? Naturally, you’re going to go on tour to show Black girls, “Look. I wrote this for us.”

BR: I was thinking about you. What did Ntozake Shange say? “I write for the colored girls who are not straight here.” Yes, there is a clause about first rights, which I know people have very mixed feelings about. To be frank, Tin House was my dream press. And still is. I was comfortable leaving it there because my rationale or my feeling at the time was very much that if we get through this process and we’re not a good fit, we’ll both know we’re not a good fit.

Thus far, everyone that I’ve worked with has been very kind, very generous, very transparent, and very much so champions of my work and what I’m working on. That is what ultimately sold me on not making a big fuss about the clause because they champion my work so fiercely. Tin House is just the sort of press that I wouldn’t mind being in their hands again.

Even more importantly if we are not a good fit, I think we can both acknowledge that and just move forward without it having to be a blowout. And thus far, I think that the instinct was correct. I don’t think they’re the sort of press who wants somebody to feel beholden to them if they are not interested, and vice versa. In terms of marketing and publicity, they have a really good marketing team who sat me down very early on to talk out marketing plans and ideas. They’re very open to my ideas, but also, they came to the table with ideas as well, which made me feel very comforted. I was super worried about marketing initially because, you know, marketing and publicity is a lot of work.

ISJ: A lot of work. We can be frank that some presses are just not equipped for that kind of labor.

BR: No, very much not. It was really important to me to end up with the press who I felt like had done right by Black women and who could handle marketing. You know, Good Dress is a very Black book, if we’re being frank, without it feeling like a token Black book. You know what I mean? So, for example, seeing writers like Khadijah Queen and Morgan Parker with Tin House, I felt assured that I was in good hands. Because I have a very specific voice. Everyone’s voice is not the same, of course. So, Ajanae Dawkins is my best friend and also a marketing guru. She just did this ad program, was at the top of her class, killing it. I’ve been joking that between her and Tin House, they are my marketing team.