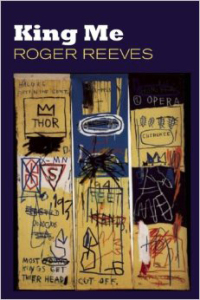

Laura Eve Engel: “Who Will Speak for This Flesh” – Roger Reeves’ King Me

King Me

King Me

Roger Reeves

Copper Canyon Press, 2013

Few words locate us in a speaker’s experience more immediately than the first three of Roger Reeves’ debut collection: “I, Roger Reeves…” As if taking up the project of consciousness-raising groups of the 1960s that famously asserted the personal is political, King Me derives its power directly from the “I.” Which is not to say that the whole of this book is stuff from the life of Roger Reeves (or even “Roger Reeves”); here, the “I” bounds from Reeves’s speaker to Van Gogh to French neurologist Duchenne to black, lesbian trumpeter Ernestine “Tiny” Davis to Walt Whitman. Unified by a lyric imagination that asserts a strong, singular voice throughout, these poems explore the various ways we stumble towards an understanding of suffering, of sublimity, and of one another across differences of race, history, sexuality, language, and the ultimate body-boundary that keeps each one of us separate. The collection takes care, too, to explore the transgressions that necessarily occur when we bridge those boundaries in the name of empathy.

Violence and ugliness perpetrated on the basis of difference is as central to Reeves’s work as it is to an understanding of America’s history and present moment. Making no bones about his intention to, as Reeves expressed in an interview, explore “the disingenuous racial history of America…and the way in which America performs this hollowing out of the black body,” the book’s third poem, “Cross Country,” asserts: “When I ran, it rained niggers.” What follows has the rhythmic and obsessive quality of one’s thoughts while running, born of exertion and exhaustion and renewed bursts of energy:

…Nigger in the squawk

and clatter of a hen complaining of a hand reaching

below her bottom and removing the warm work

of a cold night. Nigger in the reeds covering

the muck of a beaver’s hard birth. Nigger in the blue

hour of a field once wet with the breath of a lone horse

cracking along its flanks. Nigger in the fog lifting

from this field and the stillbirth it reveals. Nigger

in the running.

The repetition of the word “nigger” does some hollowing out of its own, and Reeves fills the space he’s created with images of his choosing. Often, these images contain a surface lyricism that lifts to reveal a darker, harder truth. Figurings and refigurings of these hard truths are found throughout the collection. In “Cross Country,” it’s the hen whose “warm work” is taken from her by a disembodied hand with an easy conscience and the soft reeds and fog that obscure a fatal arduousness. In numerous other poems, it’s the repeated and even lovely appearances of bees, maggots, parasites—small creatures that appropriate another body, living or dead, for purposes of creating their own products or colonies. In “On Visiting the Site of a Slave Massacre in Opelousas,” the speaker, in his grief, fixates on a beehive built inside the rotting carcass of a deer, “…the deer unaware of the work being done in its still body. / Sometimes, we entertain angels and violent strangers unawares. / You should know nothing you love will be spared.” The use of the dead deer by bees is arguably in the service of a sweet product, and yet it can’t not be seen—and felt—as invasion. The deer had its own body once. Use is use, no matter what.

And in many of these poems, we are reminded that any sweetness is a privilege of those in full possession of their bodies, though it can be afforded through a retrospective, lyric lens. Reeves’s stark, self-aware elegy for Emmett Till turns its attention to a dead horse at the bottom of the river into which the body of the 14-year-old boy was deposited after being fatally beaten, tortured and shot:

…but not this mare;

she does not get the luxury

of a lyric—a song that makes

our own undoing or killing sweet

even as we go down

into the fire to rise as smoke.

(“The Mare of Money”)

That a lyric is a luxury paid for by one’s living through its sinister motivating occasion, that from tragedy comes the possibility of a beautiful meditation on tragedy, does not mitigate the tragedy. Violence persists alongside any resilience that may have come of it, and Reeves’s poems are continually troubled by the simultaneity of that violence and the irreducible art it occasions—including his own. In “Brief Angel,” the speaker again invokes the at-onceness of undoing and song:

…Behold,

I am he whom you seek: brief angel, black fig,

Orchard fire, white tiger, lost lion—

A song of a coming destruction.

Nothing I have brought before you is unclean.

I am he whom you seek. Eat.

Even this palm stretched out before you—meat.

When has a god ever sent bread

That hasn’t required a bit of breaking, a fig crushed,

A body made to sing even as it is shattered?

Rather than turn away from any singing that’s accompanied by shattering, Reeves’s poems approach the pair of impulses with fierce empathy, acknowledging that a refusal to engage with either would be the end of both:

…the body, if allowed,

Will dance even as it is ruined—a mule

Collapsing in a furrow it’s just hewed—

The sway and undulation of the famished—

There are no straight lines but unto death.

(“In a Brief, Animated World: The Marriage of Anne of Denmark to James of Scotland, 1589”)

It is in marking the simultaneity of the singing and the shattering that we begin to understand one another’s experience.

It can be said that the moment we attempt an understanding of another’s experience is the moment we first risk appropriation. And yet that doesn’t absolve us of our responsibility to try to arrive at a method of understanding. These poems, possessing a furious intelligence about the use and misuse of the black American male experience and body, do not shy away from efforts to understand and articulate a personal resonance with the black lesbian experience, or the gay male experience, or the experience of Jews during the Holocaust, or the experience of people living with mental illness. Reeves dissects the complex conflation of appropriation and advocacy in “Of Genocide, or Merely Sound” when he writes, “I’m not allowed to speak / for people in boxes stacked / on boxes stacked on rails / because I have not been pierced / by stars or gas or hunger.” The poem goes on to suggest that the silence the speaker is entitled to in lieu of speaking—“the silence of a pomegranate / just cut open, the red seeds / pebbling a white plate”—is, indeed, a dangerous silence to keep. “If allowed, I might say / this is how genocide begins.”

As images of parasites thread throughout the collection, a poem that takes its name from the cymothoa exigua parasite, which replaces the tongue of its host with its own body, echoes earlier thinking about the dangers of silence in its final two lines: “Who will speak for this flesh: / when the tongue answers as all severed tongues do: ” In providing this literal embodiment of the way appropriation is a method of silencing, Reeves continues to articulate that all oppression and misuse that erodes the human community is at stake here, and it is this silence, universally, to which the poet lends his voice. Through a ranging selection of self portraits, Reeves’s “I” transgresses its literal identity to uncover resonances that constitute a more communal “I,” all the while exploring the uneasiness these transgressions may very well provoke. “Basho, / I am the willing minstrel with honey on his tongue, / Smearing the burnt cork of anybody’s ode onto my face,” Reeves writes, complicating the persona impulse by invoking minstrelsy, and singing of the risk his speaker incurs when he doffs the “Roger Reeves” identity for the identity of another (“In the Lone Horse and Plum, Wu-Tang”).

And yet, the alternative to risking these transgressions—staying firmly rooted in one’s own “I”—is perhaps the more insidious. In “Brazil,” the speaker, in conversation with a Brazilian man on a train, asks:

…but is this the meaning of diaspora?

I come with the dead tucked in-

to my duffle, my genocides

folded into my wallet and you

come with yours and we shout

across the chasm of this train car

comparing whose dead sing louder

or more often or now.

Reeves is careful that his poems note the difference between speaking loudly and singularly about one’s own experience, and using “I” as a form of activism. “Brazil” argues that perhaps there is a common identity to be found if we shift our categories—in this particular case, from Brazilian and Black to those who have experienced diaspora—in order to emphasize potentially shared aspects of experience. With this broadening of categories, the identities we are permitted to explore and inhabit broaden, and deepen, and suddenly Reeves’s speaker may take on the aspect of Ernestine “Tiny” Davis, whose voice is not unlike the speakers of earlier poems but bears an added sensitivity to the female experience:

…They say

[the sparrows are] tired of singing. They sang only to be noticed.

I am noticing. They are noticed. Funny little beasts

often mistaken for something that should be pierced,

a spine broken on a thorn, then eaten—breast first.

The whole of “Self-Portrait as Ernestine ‘Tiny’ Davis” is concerned with naming as it relates to identity, invoking a litany of ways to “call” the speaker and her world, resulting in the titular injunction to “Call my appetite a kind kingdom. / Call me Queen. King me.” But identity here is fluid, the distinction between queen and king nominal under the larger category of “those with power.”

In this poem, as in the book as a whole, it is through the presence of a more broadly shared, resonant figuring of appropriation and resilience that Reeves’s speaker permits himself entry to the fluidity of the mode of self-portrait as well as to a portraiture of his own experience. This collection, as rich in its music and imagination as it is in its intelligence, provides us with notes toward an ethical method of understanding and advocacy in art—a method that broadens our opportunities to speak from ourselves as well as from within our human community.

—

Laura Eve Engel‘s work has appeared in The Awl, Boston Review, Crazyhorse, Tin House and elsewhere. A recipient of fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing and the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, she is the Residential Program Director of the UVa Young Writers Workshop.