“Fishing for Icarus”

“The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool.

– Phillip Seymour Hoffman as Lester Bangs, Almost Famous

But Phil, our Phil, was so cool, in that stylish, cipher-ish, miserable way that makes a man handsome, impossible, unforgettable and rich, no matter what face he was born with, no matter what was in his pockets when he died. He used English like an invented language. When we first met, he drove me to Squalicum Beach and bantered about the moon until I ran out of jokes. We sat on a log to watch the night, swimming distance from a rotten pier whose final job was to touch all the water we wouldn’t reach. Annie Dillard set her historical epic, The Living, in Bellingham. This pier could be home to one of the book’s best cruelties. Phil hadn’t yet read it. I leaned into him, studious.

Later, a year after our paths stopped crossing, we shared a booth in a Bellingham bar, the one tucked into a one-way street that runs uphill from the waterfront. That night Phil said hi, my full name. Before I could respond he got up and left. I never saw him again.

“Get up and go,” our friend Laura calls it. The way Phil would leave a situation regardless of what others required of him. How this was infuriating, abandoning. How, when we followed him, he could sometimes set us free.

You need to know that before Phil, no one had died in our town. Even with the bad behavior, all the drinking and fucking and drugs, the oubliettes college kids carved into their weekday nights, the townies who fell into them, even then, no one had died. That’s a lie, but that’s how I remember it. When his mother found him on his 28th birthday, dead in his bed of an overdose, I felt, forgive me, like we deserved this grief.

“Every suicide’s an asshole,” Mary Karr writes.

There I go, getting suicide and addiction mixed up.

To me, he was a man who made the most sense in context. Which is to say, with our friends in Bellingham. I remember him holding hands with his love as they walked away from a party. I remember sitting next to him at a dinner of new friends, mystified by their wit, watching Phil so I would know when to laugh. I remember a man whose glances landed like punchlines as he went out for a smoke, but not a man who bought into the poker game in his living room. I remember his Speedo at Toad Lake, wearing it all July like ha! and like hot. I remember him in profile mostly. Turning away or turning toward, looking off but not spacing out. I never knew what he was thinking.

In my poem for him there’s a hitch in the last section, the “freshman from a party” line, which mentions another tragedy, a boy named Dwight who ended a drunken night in Bellingham Bay. A drowned boy, a genius actor—their deaths are tragic on their own terms, but they redeliver the shock Phil’s death gave. How easy it is, while seeking, to slip away.

My line is clumsy. It shouldn’t be so hard, in a poem, to get a body to leave a house. The later lines, the ones that stumble down Maple Street, are good. They stumble as they should. There’s unseen shade and invisible water, the weak glow of the paper factory slick as oil on the bay. When I lived in Bellingham, GP smokestacks inconstantly spewed steam that smelled like hot dogs. During the day we ignored it, we were in class. At night though, drunk on Rainier or whiskey or someone’s roommate’s Tanqueray gin, walking from one group house to another, in packs, laughing, someone always tossing the ball of conversation just a bit out of reach so another would race and strain to catch it, those smokestacks would stick from the waterfront like fuck-you fingers and make us gasp in the industrial air.

Grief, like wealth, is earned and bestowed. No one deserves it. The poem tries to contain it, but it keeps tossing things out. Rocks, fish, roadspray. After Phil, we all kept living. My ship, the township, we all “had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.”

I don’t understand addiction, but I do understand grief and loss and beauty and being young. Phil was beautiful because he wanted beauty, not because he died too soon. He was, is—like Auden’s ploughman, like everything I understand of what it is to be beloved—always turning away. “Something amazing” moving in silence. A story we didn’t yet know.

Fishing for Icarus

I. Moon

Nothing that huge should be able to move

in silence, but it does—

that’s the doom part—

so slowly we track its movements by looking away.

Apocalyptic, you say. I hear apoplectic.

What’s the difference between a dock and a pier?

Inches and air. To be lashed

to a low tide piling and left

to drown. You haven’t heard that story.

All you see is a bridge you want

to climb, beam by beam,

through cloud-rot and rust,

and walk, your arms outstretched

like a drunk gymnast’s, to the edge

where the best eyeful of ocean waits.

You brought maple bars and beer

promised to teach me the names of all the islands

I’d mistaken for whales. That’s you

skipping rocks. That’s Orcas.

II. Water

Do they ever bust themselves open? I ask,

the answer in front of us.

The creek is pregnant with salmon

and the salmon are pregnant with salmon

and as far as we can see

they’re tearing each other to silt.

Even the bank is a beach of fish,

two black slicks you feel sorry for.

You take the nearest in your arms

and walk her to the brink—

We shouldn’t help them, I say,

thinking of small fallen birds.

Your forearms are gorgeous

with scales and blood

as you toss her in and bend to hoist

the second body back.

III. Wing

We try to restart the night

by flying down Meridian in your Mercury.

Feet on the dash, I watch strip malls’

neon script blur into douglas fir

where the road crosses rain-gorged waterway.

City of subdued excitement,

you say. Meaning you know

walks pedestrians can’t find.

You want the mirrored black of the bay.

You have about three years left.

IV. Drink

When it wrecked

the leaky boat of your body,

our preacher friend said He will run

like sparks through stubble.

I heard rubble. What was left

of you is what you left. This fall

a freshman from a party

somehow drowned.

How lonely to find whatever it was

you both found. Maybe

he wanted to get the bay alone

and beyond all windows.

Shrugging off streetlight,

he must have stumbled down Maple Street

until the water stopped him.

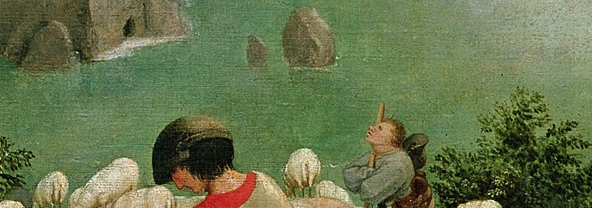

In the Auden poem about Breugel,

the ships sail on while Icarus becomes

a splash of legs.

Now here I cast a net

to drag the spot for splintered wings

and the boy who flew. I know

how art can stare a person down.

I learned that from you.

The introduction quotes from “Musée des Beaux Arts” by W. H. Auden

—

Kate Lebo‘s first book, A Commonplace Book of Pie, was published by Chin Music Press in October 2013. Her poems have appeared in Best New Poets, Gastronomica, 32 Poems, and Willow Springs among other journals, and she’s the author of a cookbook, Pie School, forthcoming from Sasquatch Books in 2014. She teaches creative writing at Richard Hugo House and pie making at Pie School, her cliché-busting pastry academy.

Kate Lebo‘s first book, A Commonplace Book of Pie, was published by Chin Music Press in October 2013. Her poems have appeared in Best New Poets, Gastronomica, 32 Poems, and Willow Springs among other journals, and she’s the author of a cookbook, Pie School, forthcoming from Sasquatch Books in 2014. She teaches creative writing at Richard Hugo House and pie making at Pie School, her cliché-busting pastry academy.

Kate Lebo’s “Fishing for Icarus” appeared first in Poetry Northwest Fall & Winter 2013-1014.

images: details from Breugel’s Landscape With the Fall of Icarus.