Jeff Hardin: “In Cultivation, Verity – Amy Glynn’s A Modern Herbal“

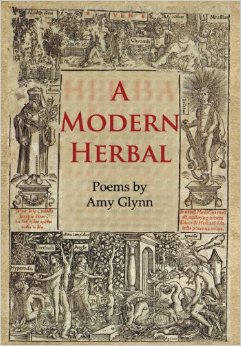

A Modern Herbal

A Modern Herbal

Amy Glynn

Measure Press, 2013

—

The poems in Amy Glynn’s A Modern Herbal are abundant, full of “hedonistic languor,” and elegant in design. They are voluptuous and fecund, hungry and elaborate. Readers can choose any title—“Foxglove,” “Sword Lily,” “Lotus,” “Sunflower,” among others—and settle in for a lush, even educational, experience. So many of the poems in this collection are not merely encounters but are, in fact, experiences, returned to again and again for their richness of detail and for how, under Glynn’s studious eye, ordinary plants and trees become not just interesting again, but archetypal.

In “European Grape,” for instance, Glynn posits that “scripture’s an attempt to wring/Essential meanings from the panoply/Of earthly possibilities.” Her poems certainly acknowledge the panoply, the rife possibilities; in fact, throughout this collection Glynn notes the abundance of the natural world, its gaudiness and flamboyance, its “multi-directional” and vivid plenitude. Like the lexicographer in “Coast Redwood,” she attempts to take “everything into the lexicon” in an effort to “[b]ring/the whole world into wholeness.” The difficulty in such an undertaking, though, lies in the infinite interrelatedness of all things, “a system that the mind/enacts at any scale.” Each thing she turns her eye toward ultimately is rooted to something else, just as each word in the lexicon is somehow tangled up in all the others.

Glynn reads the scripture of the natural world. She reads it in the night-blooming evening primrose, “sticky with longing,” and in the “Jacob’s Ladder, helix-twisted, climbing” morning glory that “bursts open at dawn.” In poem after poem, she “wring[s]/Essential meanings” from every twist and curve of leaf, from every loop and pith, finding that “there is nothing/Random in the way a space is filled.” “Nothing ever doesn’t make sense,” she asserts, a claim made convincing by virtue of a mind that searches and searches even while realizing that “blossoms always were/a smokescreen for//a darker, truer, more/essential form.”

Glynn cultivates these poems, nurturing them, trimming them, finding through sound, meter, and rhyme ways to meditate upon “the finely wrought/detail that captivates us.” From the “tight-wrapped, cryptic/onion of a bulb” in “Narcissus” to “the burst fruit’s scarlet pulp and rind” in “Pomegranate,” she takes readers into the presence of each thing-of-the-world’s luxuriance as if, by seeing clearly, the mind’s reach for meaning will inevitably transform detail into “something shocking just glimpsed underneath.” This desire to see past the surface—to see past “the tropes/we’ve tripped on,” and thus to establish new ones—figures heavily in Glynn’s thinking. After all, “clarity hides/things,” she says, and in the end, all that we may clearly see is how we see, not what we see.

The book’s first poem, “Coffee,” announces, “Wake up, you, and appreciate…,” and one hears in this assertion several of the book’s central ideas. Waking, awakening, enlightenment, illumination, realization—Glynn aches to move beyond what she knows, knowing that “[e]very meaning has its double” and that in the “transit from sui generis//to archetype, there is much to misconstrue.” Perhaps this reality is why she needs (or enlists) a “you,” a double, an intimate. “You,” as opposed to “I,” helps to make the search more than a personal quest—it makes it communal, participatory. Perhaps having an ally will keep her focused, probing onward in her attempts to name all the permutations of our shared wilderness. There may be countless opportunities to misconstrue understanding, but in the process, there is still so much to “appreciate,” so much reverence to embody.

Such reverence is on display in “Sunflower,” which Glynn addresses as “you flaming thing”:

Irrational you may be, in the way

That mathematicians mean it. But you’re all

About efficiencies, optimizations.

From apex to primordia, you spiral

Into control, girasole, you flower

Of the golden mean, the gyre, the twist, the curve.

Triumph of coincidence, master of packing

Density, attentiveness to detail.

And all this from a flower no one planted,

Arisen from last year’s spillage from the birdhouse,

Two thousand seeds for the one that engendered you.

Weary of time? I think not. Object lesson

For adepts of the trigonometries

Of Fibonacci—you are time, a living

Sundial, tireless tracker of the light’s

Trajectory. You know, you flaming thing,

You august standard-bearer for the skies

In their last and greatest clarity before

The cloudy season, you know there is nothing

Random in the way a space is filled.

Nothing ever doesn’t make sense. We

Can do the math: each thing will always be

The sum of things that came before it. Write

This message in the borders of the garden:

ɸ, the symbol of the mean you mean,

The disc atop the slim stalk. Yes, and fie,

By the way, on any and all who’d think to call

You weary of time, who’d wrongly reify

Those bending rays, that reverent chin-to-chest

Kowtow. You know of mortal gravity,

Sun-worshipper, you pythia of pith

And oil, you oracle of harmony,

Order and reason. Of course you bow to it.

In many ways this flower serves as a “living sermon,” yet the message Glynn derives is that meaning itself may be only a “mean,” an average of all things added together. The poems in this marvelous collection, added together, relish the richness of how words become a form of worship: of harmony, reason, disorder, order, connections found and connections yet discovered, knowing, and mystery. Each poem seeds down. Expect a few of these poems to reconstitute the landscape.

—

Jeff Hardin is the author of two chapbooks, Deep in the Shallows (GreenTower Press, 2002) and The Slow Hill Out (Pudding House, 2003) as well as two collections of poetry: Fall Sanctuary, recipient of the Nicholas Roerich Prize from Story Line Press, and Notes for a Praise Book, selected by Toi Derricotte and published by Jacar Press. His third collection, Restoring the Narrative, received the Donald Justice Poetry Prize and will be published in 2015.