“The Unsubstitutable Life”

by R.M. Haines | Contributing Writer

If You Can Tell

If You Can Tell

James McMichael

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016

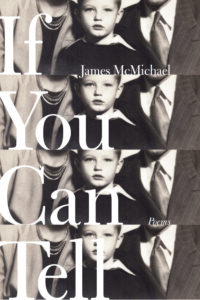

For those who are familiar with his work, James McMichael’s new book, If You Can Tell, may come as a surprise. First, there is the fact that the book—his first in ten years—makes a major return to the first-person after the rigorous impersonality of Capacity (2006, FSG; finalist for the National Book Award), in which the “I” was entirely absent. This difference is emphasized by the disarming candor of the book’s cover, on which the poet as a boy stares directly into the camera, appearing bewildered and yet focused directly on the lens. However, what is perhaps most surprising about the new book is its engagement with the problem of Christian faith. While 1974’s The Lover’s Familiar worked as a kind of Book of Hours, the religious has more often been missing or otherwise sublimated in McMichael’s work. Here, however, it is overt. One poem’s speaker is found alone, meditating on the state of being promised in the phrase “Jesus is my redeemer,” knowing that he himself has not yet been able to say it—or “tell” it—as true. Suspended mindfully between faith and doubt, the book’s eight poems interrogate how it is that such telling has proven elusive and yet singularly compelling for the poet.

Aiding him throughout are the epistles of the Apostle Paul. At thirty-two pages, “Of Paul” is the longest poem in the book, and it foregrounds the possibility the poet might “get / being right in the Pauline.” As the book’s centerpiece, “Of Paul” attempts the volume’s most direct response to Paul’s request that the poet—or any one of us—“look into [his/her] faith.” However, as the poem “Silence” tells us outright, “My faith’s not what I’m told God wants it to be. / It can’t attest / that I’ll outlive my life.” Indeed, one of the book’s signatures is the intensity of its doubt and its dissatisfaction with what Paul wants for him. Thinking the intersection of religion’s eternal promises and mortal life’s own terms, multiple passages consider that—despite Paul’s promise of life eternal—life simply can’t be abstracted from death. In “Of Paul,” one reads, “If the deity isn’t / itself death, // God / nevertheless, / that he might give all life, // takes all”; elsewhere, he asks, “Is God’s face death’s?” Here and elsewhere, the poem avers that the God of love’s reputed salvation—the life beyond death— is merely the “believed in,” not the true.

Nevertheless, belief clings to the poet. In the book’s opening poem, “The Believed In,” we read:

Only if it’s not likely to can the believed in happen.

All I can be sure of waiting for it

Is that I want it to come. I’d rather it belove that at its last the body can’t

take anymore and dies of,

alive at once to its having been made good.

Results at the end vary.

This short passage gathers so many of the book’s virtues: poignant and arresting tonal shifts; dexterity of syntax and line; and intellectual complexity wed to visceral emotional sensitivity. All of these resources are brought to bear in confronting the agonizing drama of want, belief, and (im)possibility. As suggested by the book’s title, this confrontation often gives rise to “tellings”: stories, histories, lies—gospels. The book’s opening line puts it plain: “Christmas comes from stories. / These promise that God’s love for us will outstrip death.” And there are other tellings here: stories told to the poet in childhood of a grandfather he cannot remember, but whom he supposedly knew and loved; stories the poet tells and has heard told of his early family life, especially of his mother’s dying of cancer in his childhood and of the “unconfessed” facts of her long suffering; and a lie the poet tells in church as a boy, saying he was born in China. Repeatedly, the poems confront the problem of why we tell the stories that we tell and of how those who figure in our tellings are allowed to appear and, inevitably, to vanish.

The book’s insistent preoccupation with death is, ultimately, an extension of a deep interest in imagining and relating to other mortal persons. In one line, we read, “Living is a good I don’t want stopped // even for the saved.” This sense of life’s good, and of persons as worthy of it, is the magnanimous counter to the sense that “passing away is the world’s form.” And yet the poems’ speaker is more often baffled and overwhelmed by the story Paul wants us all to live, with its injunction “to love thy neighbor as thyself” and to extend that love even to “the least of these.” Despite Paul’s promise that life is realized and preserved only in this paradoxical, “believed-in” filiation with the other—“Who loves another has fulfilled the law”—the poet experiences it, often as not, as confusion and dissatisfaction. In “Silence,” when he asks, “Who in the world // is he, / this ‘least’, // or she?”, the line-breakaccents the “is” with exasperation. Here, McMichael seems aware both of the absurdity of this notion—that one could discharge one’s debts and fulfill the word of God if only he could locate the bona fide “least”—and the inevitable desire to do it.

“Of Paul” offers the most powerful, ambitious, and surprising treatment of this estranging crux. The book’s centerpiece, it begins very much “in person”—we are with the speaker as he reads, remembers, sleeps; we are allowed glimpses into his domestic life, his loves, regrets, and hopes—but its fourth section makes an abrupt, disorienting shift into an historically nebulous period in Paris. There are clues—Eugène Atget’s photograph of a cabaret proprietor whose face has been blurred; reference to Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris, as well as various turn-of-the-century cabarets—but when the poem gravitates toward an unnamed woman on the Paris streets, the effect is provocatively enigmatic. “Who are we now?” the poem seems to be asking. The male speaker vanishes, and a woman walks the streets, musing on the shop signs and ads; she looks furtively at another man, judging whether or not he is “on the make”; she accepts another’s “flesh” as “pledge”; she follows “each call for her trade.” While it isn’t entirely obvious, a reasonable enough guess is that the woman in question works as a prostitute.[1] Thus, a plausible reading of the scene on the Paris street is that the woman has “read” a potential john as not interested in her services and so allows him to pass by without proposition:

In the stir there,

one among them charges herselfnot to misrepresent.

To get least wrong

the character her

thinking would turn him into,she looks away from someone she sees.

It may not seem like much, but in McMichael’s work, such understated moments—transient, ordinary, free of overt purpose—count in a major way. In the poems, such moments—when a being is as though emptied of itself, distracted from its purposes—offer a prayerful imagining of life mattering on its own terms.

When we leave the woman at the poem’s end, we read, “It’s been caused that there will be no / end soon // to how long she’ll go on being someone who’d lived…/ Busy // after her will be the mutual lives and deaths of every / smallest thing else.” Here, by distributing her without drama or grandeur into the body of our common, self-estranged humanity, the poem has refused to make her a vehicle for egoistic epiphany. McMichael has charged himself with not misrepresenting this woman he has called forth out of nothingness via imagination—this woman who is wholly representation—just as she herself decides not to “misrepresent” the man she turns away from on the Paris street. This getting it “least wrong” is as close as we get to salvation in the poem. In a passage that reads like an overlay of McMichael’s and the woman’s thoughts, we read, “The unsubstitutable / life of someone. / It can’t be seen // through to. / Another person’s being / can’t be got right.” In the end, there is no final discharging of one’s debts to the other.

Indeed, one salient quality of If You Can Tell is McMichael’s repeated checking of any drive—be it his own or his readers’—toward thoroughgoing affirmation. The reader is never allowed to stray too far from the opening poem’s reminder that “results at the end vary.” Nowhere is this more apparent than in the (at least) dual implications of the book’s final lines: “Death’s still to be heard from at its least reserved. / Under its breath it primes me to pay up and look pleasant.” Here, death’s whispering suggests, on the one hand, the voice of a mugger insisting that one misrepresent oneself and hide one’s panic before anyone else notices something is wrong; on the other, it is a reminder: a charge that one make good on having represented God as “benign” and “for us” by enacting those virtues oneself and continuing to offer care, sincerity, and love even as one draws closer to one’s passing. Is Death a thief or somehow a gift? Fittingly, the difference between these readings is, for me, unresolvable—something of which I can’t, with certainty, tell. With the poems as guide, however, I am led to contemplate a space in which such uncertainty is not a mark of loss, failure, or mere enigma, but the matrix of a pained and wondering generosity.

[1] While this transformation within the poem is completely unexpected and disorienting, it is entirely in keeping with the early Christian milieu with which the poem is in dialogue: one thinks of Mary Magdalene, Thecla (the prostitute whom Paul reputedly converted), and the Desert Mothers (many of whom were penitent ex-prostitutes).

—

R.M. Haines is a poet whose work has appeared in (or is forthcoming from) Kenyon Review Online, Poetry Northwest, Poets.org, Salamander, and Spoon River Poetry Review. He lives in Bloomington, Indiana.