Interview // “Demonstrating / Monster”: A Conversation with CD Eskilson

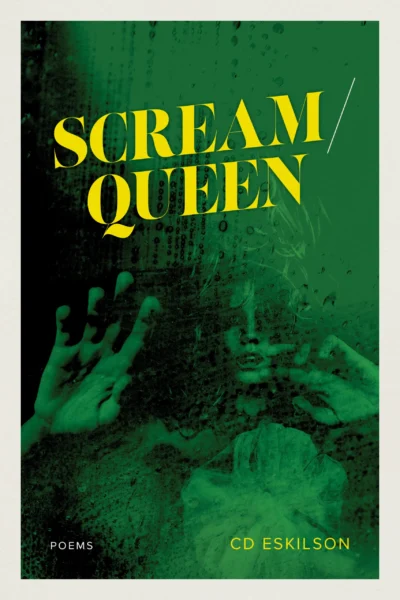

CD Eskilson’s incredible debut poetry collection asks us to examine what happens to our connection with our bodies when experiencing and perceiving them via a language based in violent binaries. Their work is a lyrical invitation to consider what monsters might demonstrate, what it means to act out what society views as horror, and how the body, particularly the trans and chronically ill body, is surveilled by a society whose language is inherently hostile towards it. Scream / Queen (Acre, 2025) is not only diagnostic, but foresees a reality in which transness is synonymous with beautiful, with unlegislated connection to self and community, and also with monster. I was so happy to have the chance to ask CD these questions via a Google Doc.

*

Alexa Luborsky (AL): I wanted to ask a question about the title / typography (see what I did there?). The slash here is not just something that occurs in the title, Scream / Queen, as I had initially thought. But, in opening to the table of contents, we see the section titles continue this pattern: “ FOUND / FOOTAGE,” “BODY / HORROR,” “JUMP / SCARE”…etc. So first, I am wondering, when I have heard you speak about the book title aloud, you have chosen to say “scream queen” and not “scream slash queen” or “scream [pause] queen” which is interesting in itself because then it becomes an unvoiced caesura that is only rendered visible on the page. And when we get to “During Intro to Film Theory” we have the title phrased again without a break (in lineation or in typographic slash): “every scream queen / flagrant with her brilliant smile.” So first, talk to me about the slash, and talk to me about the title!

CD Eskilson (CDE): Firstly, I applaud the pun in your question / questions (sorry, another pun). I’m so glad we’ve met in person so you could zero in on this visual and spoken dichotomy! The convention around its select utterance imitates the way we typically disclose pronouns: she/her, they/them, etc. There’s a visual distinction in a written format but we most always say “she-her” or “they-them” aloud. It’s a custom I’ve always been intrigued by. Maybe we avoid it because saying “slash” carries such an inherent aggression to it?

Within the book’s context, though, this unvoiced caesura (which is a gorgeous term, by the way!) came out of a desire to interrogate how we language gender as a construction. How language, which functions to uphold and articulate social conventions, fails to identify those of us outside of those conventions, i.e., trans and nonbinary people. In a way we haunt language by being physical but not always being effable. As a result, the book’s title is meant to be ghostly—a pause with troublesome qualification, an odd hiccup while experiencing the collection. The book’s title and therefore its identity remains an open question, something that’s not fully captured by either mode of communication. It’s something not yet invented by the binary construction of our language, something rendered only through the poems that it contains.

This probing of binaries continues as the slash returns in the section titles. Each one comes from a trope or subgenre of horror speaking back to the poems housed within it. At first, the slash divides two distinct words but then comes to bisect a single word, forcing a rupture contrary to what we know about the identity or meaning of the word. It’s an arbitrary convention whether these words are or are not divided—something that’s analogous to ways that gender gets constructed. I hoped to capture here how language is so implicated in patriarchal violence.

On a literal level, “scream queen” is a film term denoting an actor who’s starred in a number of horror films and reached icon status within the genre. This includes actors like Neve Campbell and Jamie Lee Curtis, while Jenna Ortega, Mia Goth, and Anya Taylor-Joy are some current examples. There’s a cyclical implication behind the term—throughout the actor’s various roles, she has repeatedly encountered unprompted violence and often survived it. This positioning symbolically parallels the speaker of Scream / Queen. As a trans nonbinary person, the repetition of unprovoked violence on personal and structural levels is very familiar to them. Repeatedly working to survive the near impossibility of that violence is familiar, too.

AL: Inheritance is a big part of this collection. Inherited body, inherited audience, inherited expectations that induce a “jump scare” as the speaker puts it when they come out in “How Are They Picking the Next Halloween Director?”. This feels entangled with the relationship between the sibling and the speaker in this collection. “My sibling postulates how ordinary growing up was, how little we’d known about what’s heritable until later. Until trying to form relationships and being too much every time” (from “Recipe for Roasted Broccoli”). The sibling never sees the speaker or their family dynamics the same way or maybe even in the way the speaker themself wants them to maybe? Like when the speaker is called “little F.” and they note how quickly their name is erased in “On Witchcraft.” Or how the speaker wants to “prove them right” with their gesture of tossing broccoli neatly into the trash but they miss in “Recipe for Roasted Broccoli.” We also learn that the sibling’s body is in danger most clearly in the very last poem “Draft Message to My Sibling after Top Surgery.” The sibling is an example and at the same time something that stands in opposition to the speaker and how they want to be perceived. This feels connected to performance and audience and movie…and I’m wondering if you think so too or if you’d want to talk a little bit about that relationship in the context of the poetry book and how it informs or disarms the speaker of their own identity? What does seeing different things while sharing an intimate reality do to the speaker’s perception of reality and self? Also, the “monsters” of the collection show a different heritage the speaker can use to relate their body and how their audience “expects” them to perform themselves. For example in “Update on HIM from Powerpuff Girls”: “HIM reminded me of me: of something / queer and clumsy that attracted too much notice.” And again later: “They kept apologizing / same as when I asked my boss to use my new name / and he wouldn’t. The sorry added to my hands.” If the sibling demonstrates (and I’m using this word because you taught me the importance of its etymology for your thoughts about monsters so I’d love for you to share that here if it feels good) one particular mechanism of heritability, then the monsters perhaps show another? Or do you feel these are linked? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

CDE: Our siblings uniquely share in the specific set of inheritances informing our development as people. Throughout life, though, our individual relationships to those inheritances might diverge or converge based on various external factors or decisions that we make. While writing specifically about experiences of trans siblinghood—that is, having a biological sibling who is also trans—I was interested in unpacking the complexities of living with a duel set of inheritances. Both literal familial inheritance—hereditary conditions, generational traumas, or childhood memories—as well as the inheritance of trans history, political organizing, and representation.

As someone struggling to accept their identity, the speaker of the poems in Scream / Queen finds their sibling is a guidepost towards the future they want to live in. But still there arises an internal and external pressure to agree, both about both the reality of their family and the varying trajectories of their gender journeys. The speaker and their sibling can validate one another, but can also offer an at-times unhealthy point of comparison. With that in mind, poems work to sit in the discomfort of that sibling divergence and eventually embrace the multiple realities that can stem from shared inheritance. That there is no one script to follow when it comes to finding self-actualization or identity.

This tension also follows Scream / Queen’s speaker throughout their encounters with the book’s monsters. Though they’re fictional, the poems’ creatures and creeps share in and continue a legacy of vilification that the speaker relates to. Such moments reference back to the linguistic origins of that term—because what are we really saying when we call something a “monster?” The word itself is thought to come from the Latin word monstrare, meaning ‘to demonstrate’. In this sense, the monster is quite literally demonstrative—it reveals a deeper truth that challenges society’s dominant conventions. In a counter-reading of this, monstrous representations offer an example of how to defy and endure in the face of a hostile social climate. But an overarching question for the speakers becomes how do they learn from these demonstrative figures without belittling who they are presently. How do they admire others while acknowledging their need to diverge from those examples? The speaker ultimately has to learn how to embrace their real-world desires and needs beyond the monsters’ allegorical lessons: to write the script for the movie they want to star in someday.

AL: This is part question, part comment. You have the most amazing titles. As someone who struggles with titling, and I think for that reason works in series a lot of the time to avoid the idea of separation that is created when a reader sees a title, I love how yours work with typically some sort of allusion that disallows for the “closure” that I feel skittish of when thinking about these as markers of finality. Like “Finsta of Icarus in Drag” or “Fan Mail for the Headless Horseman” ! Can you talk to me a bit about how you think about titles, when you write your title, how you think about allusion maybe as a method of duality or twoness as in the what is being echoed from myth or movie and what is being altered or changed or traversed in how the allusions are qualified in the words that surround them in the titles?

CDE: Thank you! That means so much since I admire how well you craft poetic sequences and the directness of those titles. In writing Scream / Queen, I sometimes worried about assigning titles that made poems seem too self-contained or obscure to a reader—ones that required readers to visualize a particular occasion or scenario that only I really had access to. Some of that fear was a result of how much allusion the book is working with, but I eventually came to trust that folks would investigate an unfamiliar reference if they could at first access the poem’s story or emotional terrain. If readers could connect to the poem’s language in a way that wasn’t so reliant on understanding the allusion, the title wouldn’t have so much pressure on it. Overcoming concerns with titling also meant letting go of a lot of working titles. These titles were often the first thing I wrote—the initial utterance of an emotional truth or image system which the shape of the poem resulted from. These had helped me bring the poem into the world but couldn’t necessarily follow the poem as an object being shared with others. Accepting that something might be my title for the poem but not the title for it helped me revise towards crafting an engaging container for each piece.

Additionally, I think my approach to titling poems in Scream / Queen stems from a broader project about constructing a poetics rooted in possibility. Possibility meaning that there is space for multiplicity and contradiction surrounding one’s desires for the future. Possibility as the permission to rewrite what has been written. Across all the poems’ references and revisions to monster stories is the speaker striving to possess the agency to find out who they are. To craft the self or selves that they want to become despite external violence and self-doubt. I ultimately came to see each poem as an opportunity for the speaker to explore an aspect of themselves or confront some outstanding harm in order to change their relationship to that moving forward. As a result, the titles for the poems had to leave space for possibility to enter the poems. It became vital that the very first instance of each poem granted permission to all that followed.

AL: This is kind of a two part question, sorry for the length in advance! So first, do you feel like writing this book has changed how you feel in your own body? I ask this because there are a fair number of aspirations that are expressed in this collection and I’m curious if what you want or what you’re looking for is different after writing this collection? For example, one of the lines I love that comes early on in the collection, in “On Witchcraft,” is “I want to be the open field and commune. To coven in a word like them and reclaim multitude as gender.” And to quote you, speaking through King Paimon in “The Demon King Paimon Come by for Monstera Clippings,” (obsessed with the title fyi) was this book finding a way to “let light adorn your head first” so that “soon enough you’ll wear it”?

Part two of this question. I’d also love to hear about the dangers of “conjur[ing] what [you] can’t contain”; also a line from “On Witchcraft.” Being multiple feels at odds with being or feeling like “enough” which is another word you use in this collection in reference to identity. One example is in the poem “Deleted Scene: Each Time I’m Trans Enough.” To contain is different than to approximate, but living in proximity to what you want to be is…untenable. The first poem, “King Ghidorah” has this kind of haunting image that I was so drawn to:

One scene from a movie I recall’s

a father helping children stack the rubble

into play forts, crawl inside

the avalanching walls–

how they don’t seek protection in the wreck

but proximity to its ruins,

I kept reading this as “protection from the ruins” but it says “protection in the ruins.” What does it mean to seek protection inside the ruins of this “role” that the speaker is kind of being asked to play given the society they are living in? “Protection from” would mean that the lack of safety was something only external to the speaker, and not also something inherently inside. I’d love to hear thoughts on proximity and multiplicity for you and how it relates to gender and self.

CDE: Regarding part one of this question: yes, I do think writing Scream / Queen changed the relationship I had with myself. The act of articulating desire in a poem, of committing emotions to language and then holding onto those aspirations in the lines of a poem made the idea of living as who I wanted to be feel less impossible. The poems provided some initial accountability and gave me something to work towards. Over the years when the book was still being written, though, I still had to contend with the actual living part, the at-times unpoetic reality of surviving. The hard part after imagining through poems was concretizing the life I wanted through the small wins, the big wins, and the failures of navigating gender identity. At this point in my relationship to my own body, I try to carry forth the shape of the speaker’s journey and their relationship to progress: of letting myself sit with the change that has happened and also recognize how to let more change happen. That intention feels analogous to letting the light crown my head, as your quote from Paimon (who’s the demon in the movie Hereditary) here references.

Regarding part two of this question: to me, that line from “On Witchcraft” speaks to an epiphany many trans and nonbinary folks find when realizing they’re not the person they’ve been told that they are all their life. In online trans parlance, that realization is often called “cracking the egg.” I think the line injects more agency into the egg scenario with a summoning metaphor, along with reframing the speaker’s body as a container or structure running up against its own limits. Because as you point to with that line from “King Ghidorah,” there’s a metaphorical ruination of the old, alienated self during that process—the body is no longer a stable thing or structure that can house you. The realization around identity is devastating for the speaker in Scream / Queen, but it also allows for potential. To rebuild. As a result, their body transitions throughout the collection to no longer be the mere container that it was when they were in denial.

I think the danger or rather the risk in this conjuring, in cracking the egg, is that it cannot be reversed. You cannot unlearn the idea of who you could be. And for me, the awareness that there was more to my identity than what I understood in the present moment was terrifying at first. That’s the horror behind a movie like I Saw the TV Glow. And to your other point, I think another risk in that conjuring, in starting that journey, is having to accept that the idea of being “enough” may always be in flux. You will be the one who determines what is authentically “you” in different situations moving forward, what is needed to endure.

AL: Still continuing with “enoughness” but I wanted to bring it into a more general concern with language that feels also to be echoing as a failure of self/society. “There’s so much harm silenced, so much / cruelty made quiet” (from “During Intro to Film Theory”). Naming seems to be a potential remedy in that sense, and in opposition to the “silence” or “namelessness” which are brought into proximity: “To rename is to seize through language. To keep nameless is to hope that something vanishes so no one has to answer for it” (from “The Ocean Within Me”). But all of this feels complicated by audience. In “During Intro to Film Theory” you also write: “What angle could I film from to grip an audience and capture / all the care inequities? Without red dye, / people shrug, stay unfazed by our loss.” And in “My Roommate Buffalo Bill” the speaker says: “I’m scared to own a self.” And later: “I ask why, picking at the numbers on the remote. You can’t live as an idea. A performance.” Do you think of words as ideas/performances or as bodies/selves? How does the audience intervene in the space between performance and self? Who do you imagine in this “audience” for you or for your poems specifically? In some ways I think you might be speaking to “audience” in the sense of “mythos” where film or language becomes a medium for hegemonic logics to form and then inform how the body is experienced on a personal level. I see that in “At the Midnight Show of Sleepaway Camp”: “A trans girl romps through teens’ dark cabins, the panicked cry of She’s a boy! to give this slasher its shock twist. Today / the image we’re all killers remains deadly.” And in “Prey: A Gloss” as well, for example: “So much language is a hunting ground.” Does that feel true for you and, if so, how do you feel about the medium you’ve chosen to speak to this in (a very artificial, as in a medium that is perceived as “true” or “raw” but is artifice?

CD: I’m so interested in the point you’re making with this question—it brings up a broader struggle with the nature of language I think all poets need to work through. We have to reckon with the fact that our art comes through a compromised medium. Written expression is not intrinsically benevolent or inherently a vehicle for positive change. It can be a hunting ground, as that line from “Prey” asserts, because writing has been and continues to be a tool for inciting violence and justifying it later. For instance, a written law names who is a criminal or unworthy of personhood by the state. At the same time, though, written expression can provide a conduit through which the possibilities for collective liberation can be articulated. To that end, I would say that I often consider language to be an act of performance because, as you noted in the question, the occasion and audience for that expression is central to bestowing it with transformative power. Poetry’s language is an approximation of emotion that earns meaning based on who is interacting with it in a particular context.

I think your question’s premise about the social aspect of language also gets at a larger goal I had in writing Scream / Queen: to trouble language’s relationship to identity. In American English, patriarchy and its constituent components like transphobia, homophobia, ableism, etc., infects the rhetoric that we use to express ourselves. It demands normativity, binaries, objectivity. So if our expression is rooted in those structures, how can we conceive of ourselves, write poetry about ourselves, outside of that epistemic violence? In writing these poems, I’ve leaned into the mystery of poetry to help language myself beyond the patriarchal demand for “clarity” or “sense” or the need to provide one answer to a question. I’ve leaned into reaching out to connect with readers who are also contending with that unease around expression. I would say I imagine my audience to be other folks whom language has othered or marginalized and who are interested in changing that dynamic, who want to reclaim agency around how words perform. Poetry has the potential to enact radical performances with language if we center that intentionality—if we enter into writing knowing that we must be defiant with our words.

AL: There are references to withering, not feeding the body to try to shape it into something that will be cared for. There are also references to cutting. I was also a cutter to try to make myself feel…just…less. I wanted to manage emotions like they were enemies that I had to drive out of my body via a rush of endorphins. When I read, “Nobody told me knowing / would do little,” in “Heredity,” it felt really resonant to me of my own search for something stable to attach myself to in order to be able to view myself because I didn’t feel like I could do that from the vantage point of my own body. Knowledge was a kind of anchoring for me. And, as you wrote here, that logic is faulty and becomes an extreme let down. What are your poems interested in doing instead of knowing? Do you think of “myth” maybe as an alternative to “knowledge”? If so, when you write, in “Portrait as a Werewolf”: “Flash a fang for you / and hope to graduate from myth,” what does graduating from myth look like for you? Secondly, and maybe relatedly, how does this notion of self-making, “What’s a monster // but a body deemed impossible,” interact with myth-making? I’m asking this question selfishly: if you aren’t writing towards or trying to find a way into a body that feels habitable via it being “knowable” to you, what do you write towards?

CDE: For a long time, I used knowledge as a defense mechanism and a means of gaining validation from people whose rejection I feared. I thought if I was smart enough, if I was valuable in that way, that I would be safe from rebuke for potentially failing in other respects with my queerness or transness or neurodivergence. But I think that constant need to intellectualize everything around me made it easier to dissociate and ignore all the signs of dysphoria. Obsessing about knowing permitted me to alienate myself from exploring who I was or living how I wanted to. As I identified this and worked to unlearn it, I think a lot of my poems grew interested in analyzing transformation. In creating opportunities to spotlight flux and accept that as a more compassionate alternative to how we typically view knowledge—as something static, objective, a thing to be coveted. My poems want to leave space for change now, to leave space for all that I do not and cannot know.

Myth really does feel like an alternative way of understanding to knowledge. It holds so much power because it is so mutable, and that’s an aspect which frustrates our modern conception of knowledge being a product. You cannot claim ownership over the countless versions of a myth. And whenever someone tries to, the veracity of details, the believability of a myth’s plot is never the actual point. It becomes meaningful through our personal engagement with a story, through the lessons we decide to take away from it. It’s this subjective and interpretive aspect to myth-making that drew me to write through the lens of horror, a genre that has been both empowering and problematic to marginalized folks over time. The terrain of myth allowed me to engage in meaning-making: to claim and recontextualize monstrosity as a way of taking power back.

AL: Thank you so much for your time with these questions. I’ll be sitting especially with this last response for a while.