Interview // “War Poesis”: A Conversation with Oksana Maksymchuk

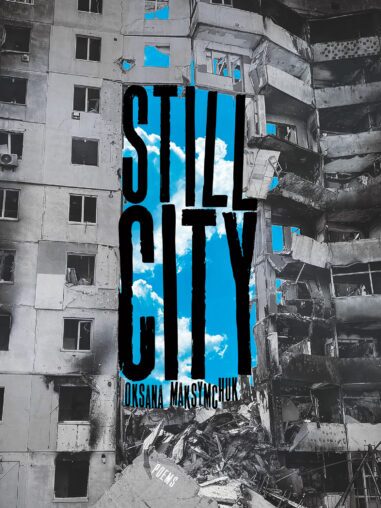

Oksana Maksymchuk has crafted a unique book of poetry among the many coming out of Ukraine. Unique because Still City is unflinching in its study of the effects of war on culture. Maksymchuk’s experience has outfitted her with an epistemological array suited to the unforgiving and terrifying, yet ultimately enriching task of crafting poetry about war. Unique because out of her multiple languages, Maksymchuk has chosen English to undertake this task. Our conversation took place over a shared document, but I was struck by the way the meanings of words began to dissipate as if the knowledge we brought to our conversation was disintegrating and being formed again in front of us. Maksymchuk tells us that there are no easy answers to the violence and death that war forces people to confront. But language that attempts to give shape to our senses can also attempt hope.

*

Ian Ross Singleton (IRS): In her foreword to your book of poems Still City, subtitled Diary of an Invasion, Sasha Dugdale writes, “Maksymchuk is a poet first and foremost, rather than a witness. The poems are made for poetic effect, adjusted, pared back, the mot juste selected.” Indeed, you reflect on the very process of poeticizing about the war, of reflecting on past texts that might help us make some sense of what’s happening in Ukraine and the world right now. Yet you also express skepticism about this process. Could you explain this dynamic: of writing poetry about war and yet questioning this form of writing at the same time?

Oksana Maksymchuk (OM): In the face of tragedies and crises, and even with positive liminal experiences like giving birth or falling in love, we often hear phrases like “words fail” or “I’m speechless.” These expressions, even if cliché, convey an appreciation for the fact that language is somehow inadequate, limited. One problem with language, of course, is that it works through abstraction: the word “home” stands for all the homes, in this world and in any other world in which homes exist; just as the verb “love” refers to all the different types and instantiations of love, not just to the burning, overwhelming private feeling for a specific beloved person the speaker or thinker may be experiencing at the moment. This feature of language seems to muffle the uniqueness and richness of individual experience, while at the same time enabling us to share it with others. Still City thematizes this feature of language and of poetry: the erasure of uniqueness and the loss of specificity, the constant oscillation between reduction and rendition, the contrast between the raw, messy, lived truth and its tidier, flattened, “enformed” reflection in words and images. What are poems for in the darkest of times? Why write them? To what end? There are no direct answers in my book. But perhaps the book itself is a kind of answer. It has to do with attention and memory; with a quest for agency, freedom; with a desire to find order in the chaos and get outside of the present moment. It’s an attempt at transcendence that is, nevertheless, grounded in embodied experience, profound vulnerability, and mortality.

IRS: You have a PhD in ancient philosophy. Do you find yourself drawing on the materials you handled in your studies when you write these poems that are very much about a contemporary setting and situation?

OM: In the months preceding the invasion, I was working on a paper about civic virtue for The British Journal of the History of Philosophy with my friend Andreja Novakovic. A few of the poems emerged out of my engagement with G.W.F. Hegel, and with Andreja. “Rose,” a poem about a flower hidden in the cellar, pushing against the war with its serrated petals, compelling the speaker to dance “here” (rather than trying to escape this terrible real moment for some better imaginary one). The poem “Blank Pages,” about periods of happiness leaving no marks in history or a narrative of a life. I also have an incomplete poem reflecting on Hegel’s quip that what we learn from history is that we don’t learn from history. I suppose my conversation with Hegel is episodic—I’ve sampled a line or two, finding in them fruitful portals into our own situation. My engagement with the ancients—Plato, Aristotle, the sophists, the Atomists—is more architectonic, pervasive. I’m drawn to their systems of thought: their ways of making sense of this or that phenomenon; how they engage with their interlocutors; what it means for them to give an account or explain something.

Something similar happens when you’re a student of history. I know that to many younger people these wars we’re living through seem to be all that matters. This is understandable, but it also makes it more difficult to find a basis for solidarity with victims of violence and injustice in other parts of the world. Staying mindful that each war is one war among others; that every war is bound to have an end, just as it had a beginning—this helps the suffering lose its edge a little.

Take Ukraine, for instance. Our enemies are not uniquely evil; they are flawed human beings suffering from a bout of terrible moral luck, committing crimes because they’ve dug themselves into an epistemological, spiritual, and practical situation some scholars would describe as atrocity-producing. Reasoning with them in their current state is like reasoning with a drunk: they’re intoxicated by the myths of superiority and terror their KGB-trained leaders, experts at manipulation, have been feeding them for generations. In that kind of setting—growing up in a police state, where all forms of dissent are punishable—your chances to become good are slim. Even the church treats this war as a crusade, encouraging self-sacrifice, and any dissenting priest is stripped of his status.

Yet many of my friends in Ukraine demand a much more severe judgment of the Russian invaders: that they’re inhuman, incapable of empathy, unworthy of pity; that we owe nothing to them. Nowadays, we tend to make the mistake of using “humanity” as an aspirational term, some ideal we strive to embody, implicitly containing a set of standards we hold ourselves and others to; which in turn causes us to feel shocked by the actions of those who do not abide by those standards. In fact, humans are capable of a wide range of behaviors, and some of these behaviors involve inflicting gratuitous suffering, predatorial abuse of the vulnerable, wanton acts of destruction, torture. These tendencies are as human as are our capacity for empathy, generosity, self-sacrifice, humor, the compulsion to create art and solve equations.

IRS: Your poems such as “Genesis” and “Kingdom of Ends” remind me of the final work of the late Cormac McCarthy. The latter poem captures a labile feeling about nuclear weapons and nuclear power, which has become weaponized by Russia through the occupation of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, and about a kind of “rebirth” that can happen through fire, through suffering as great as that which war imposes. Is language somehow complicit in this process? Is it a weapon, or a kind of “pharmakon”?

OM: “The Kingdom of Ends” is trying to imagine a way of describing a world—our world—after humans disappear from it. I think it’s agnostic about how that disappearance happens, its mechanism and speed. It could be a rapid explosive annihilation, or perhaps a slow fading. All living beings are impermanent, and this, for me, is a source of both sadness and relief. I don’t think we should be striving to survive at any cost. Rather, we should be trying to live the best lives we’re capable of, something that’s extremely difficult for our clever and opportunistic species to agree on, let alone accomplish.

I wonder if the “language” the poem speaks about—the one developed between the world wars—is the language of nuclear physics, as you suggest. Perhaps it does refer to the formulas that attempt to “solve” our energy and security problems and inadvertently create an opening for a solution that is far more encompassing and irreversible. The whole poem is certainly atomistic in spirit—it’s about a transformation of matter through fragmentation and recomposition, the new life that will emerge out of particles that currently make up our breathing, heaving, separate bodies; the mixing of opposites—the good and the bad, the friends and the foes, the perpetrators and the victims—within a single biochemical process, without the satisfaction of a redemptive religious narrative, or a neat teleological explanation.

IRS: Can you discuss a potential tension between poeticizing about this conflict in order to “begin again” (a quote from “Genesis”):

a word—a formula

once it’s all over—for

how to begin

again

How might such a process be misappropriated or misused by an enemy such as Russia?

OM: Poesis means, literally, a process or activity of creation. It’s the origin of the word “poem”. The world, according to the first lines of Genesis, is a poiema: a result of creation. Even if what we usually mean by poems and poetry constitutes a small subset of all episodes of creation, the poem is a reminder of the fundamental principle at the core: complexity unfolding out of simplicity. Many poets describe their process of inspiration as a phenomenologically rich experience, a kind of humming resembling distant music, or a single word oscillating, dividing, exploding into a more complex whole. Poets sometimes experience the onset of inspiration as an ecstatic abandonment, or as utter destruction of the self. In this sense, the emergence of the work is contemporaneous with the emergence of the new self. The work and the self are coetaneous, if you will, and co-determining. Just as you create the work, so the work creates you. It reconfigures you into something you were previously not. I don’t like to explain my poems, that would be to fix their meaning—if it were possible, why didn’t I just provide the explanation, in the form of an essay or a treatise, in the first place? Why write a poem that attempts to say the same thing? But I’m hoping this helps sketch out the contours for a possible interpretation.

IRS: “Orphic Euphemisms” (quotations from these poems above this question) refers to a woman “getting killed” instead of “dying,” hence the euphemism. The last two and a half lines of “Water Under the Bridge,” a title suggesting forgiveness, are about “a poem’s flow // reflecting everything / changing nothing”. Can you discuss what sounds to me like an attempt to unify what can be victorious about poeticizing and what can be defeating about it?

OM: Poets often take familiar words or phrases and make them strange, unfamiliar again. Reading a poem should give you a bit of an uncanny feeling, like you’re learning your language for the first time. You could say that poetry is how language renews itself. In this context, “Water Under the Bridge” is a Heraclitean poem—it’s about the instability of idiom—but also about flux, change, and absence. It seeks to upend the original, comforting meaning of the phrase. Not necessarily to turn it upside down, but perhaps to de-root it, make it flow again. Perhaps the poem itself is a plea for forgiveness or absolution on behalf of poetry. Or perhaps it’s an apologia on behalf of language, more broadly: its inability to continue functioning as a bridge between people.

I realize such confessions of built-in ambiguity may be frustrating for those who attempt to make sense of the work. One reason for this resistance to offer conclusive authorial interpretations is my belief that the poem only becomes complete when it reaches the reader. This is not to say that there aren’t interpretations that are simply off or implausible. But I wonder if I’m the best judge of that? And if not me, then who?

I’ve previously compared poems to wishes—a privately formulated sentiment, whether good or bad, that becomes fulfilled when the world around it changes to fit it. They’re also like oracles— they reveal themselves differently to different people, and differently to one and the same person at different times.

IRS: “Orphic Euphemisms” also made me think of Victoria Amelina, with whom I had discussed publishing war diaries from another Ukrainian writer killed in the conflict, Volodymyr Vakulenko. Amelina discussed, in this podcast, how writing in English helped her find a “distance” to write about such things as war, so difficult to discuss. You’ve said in an interview with Sasha Dugdale for PN Review (Issue 272, Summer 2023) that writing in English creates, “the illusion of temporal distance, which allows me to speak in a freer, more even voice.” Can you discuss both the advantages and limitations of this “distance” you mention?

OM: “Orphic Euphemisms” is a poem about how language covers over sites of violence, fills out unbearable absences. This strategy helps us survive and carry on, but it also stitches over the terror and irreversibility of each loss. We name what is not there to make it present, but the presence takes the form of memory or fantasy, and not of resurrection or restoration. I sense that what this specific poem wants is to expose and ruffle the gauze over some of those wounds by changing what words we use to describe what is happening to us.

After Victoria got killed in the summer of 2023, her friends shared beautiful narratives about her. One saw a dream of Victoria in the garden, surrounded by flowers. Another had a vision of Victoria looking over her friends from an idyllic, misty place, an island in the sky. In remembering Victoria on the first anniversary of her passing, friends have generally shared these hopeful, lovely images of a parallel reality in which she continues to exist. It’s as if she moved away to some distant country. I am troubled by such images: how they swaddle violence in soft, beautiful stories crafted to make suffering and injustice bearable, preserving the status quo that serves the powers that be, even if it does offer psychological comfort to the victims and survivors. Yet I’m as drawn to such images as anyone. I too rage against the finality, the terminus.

I did not write this book in a language I consider genuinely foreign, but that I know well enough. It came to me in a language that I speak with my child. It’s a mother tongue in our family. I’ve lived in the U.S. since I was a teen. I went to high school, college, and to grad school in the Midwest and on the East Coast and I taught at a university in the South, on the lip of the Bible Belt. I’ve been habituated to inhabit multiple identities and perspectives at the same time, to toggle between them. Yet prior to 2015, Ukrainian was the primary language of poetry for me. English was an academic language, one in which I was accustomed to fulfilling professional duties, and in which I was more likely to censor myself. The experience didn’t block my creative energies—instead, it channeled them into my second tongue—like water flowing into a river bed ready to receive it. I wrote a cycle of poems about this war in Ukrainian in 2014-15. But I also felt that my subject was too close, rendering me myopic. And the emotional proximity made me feel like a surgeon operating on a gigantic body in a tiny room, under surveillance.

IRS: You mention, in that same interview with Sasha, that you first learned to curse in Russian. Does this experience mean that Russian has a negative feeling for you? How has war changed your attitude to the language?

OM: In the interview I say that Russian was for me “a language of intrigue, and sex, and everything prohibited we weren’t supposed to speak about—a language that held our dirty thoughts and adolescent anxieties.” It was an exciting, transgressive tongue.

I met my husband Max at the Ukrainian Writers’ Congress in Yalta in 2003 he spoke no language other than Russian—in fact, a common predicament for speakers of the so-called “world languages”—so that’s what we spoke to each other for the first two years of our relationship. He ended up going to graduate school in the U.S. and wrote his M.A. thesis on Osip Mandelstam’s poetry of terror, and his dissertation on Marina Tsvetaeva’s poetry of war, which ensured that Russian poetry—from classical to the most contemporary—remained a constant topic of conversation in our household for well over a decade. My immersion is so deep that even though I’d never write in Russian, until recently, I knew the world of Russian poetry better than the world of English-language poetry, and just as well as I know Ukrainian poetry, a classical ‘diagnosis’ for a post-colonial subject.

But since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, hearing spoken Russian does trigger me. I become anxious, hyper-attentive to my environment, as if I am in the presence of something dangerous or potentially harmful. I am not recommending that others cultivate this reaction, merely describing how I feel.

Why do I feel this way? I suppose because I’ve now come to associate the speakers of this language with the Russian population that, in its majority, either approves of the current war, or doesn’t care that its country is inflicting irreparable harm on its neighbor. There are a few dissidents—you can’t call them opposition because they’re politically sterile, disorganized, and scattered—but aside from them few people in Russia have protested against the war. When they did, it was usually when the war effort went against their perceived self-interest: when they or their children were drafted. To me, the language is now associated with moral unscrupulousness, spiritual hollowness, with sadism and torture.

Think of a place you love to visit, a beautiful forest or a lake, and imagine something terrible happening to it, whereby it becomes toxic, even though, perhaps, not much has changed about its outward appearance. You can still appreciate why you were formerly drawn to this place and may have fond memories. You may even dream about visiting it at some point in the future. But you may want to avoid it until it’s no longer going to give you nausea and radiation sickness.