Interview // “Speech Crush”: A Conversation with Sandra McPherson

by Nan Cohen | Contributing Writer

Sandra McPherson’s first published poems appeared in Poetry Northwest in the Autumn, 1965, issue, edited by Carolyn Kizer. Since then, she has moved from Seattle, where she studied with Elizabeth Bishop and David Wagoner, to Portland, Oregon, and then to northern California, where she taught creative writing and literature at the University of California, Davis, from 1985 until her retirement. Her books include The Year of Our Birth, The Spaces Between Birds: Mother-Daughter Poems, and The 5150 Poems. Her honors and awards include fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation, and her work was also featured in the Bill Moyers PBS series The Language of Life. In 1999, she founded Swan Scythe Press, which still publishes poetry chapbooks. Her twenty-second full-length collection of poems, Speech Crush, was published in late 2022 in the California Poets Series of Gunpowder Press in Santa Barbara. She lives in Davis, California.

This interview was conducted over e-mail in January and February 2023.

*

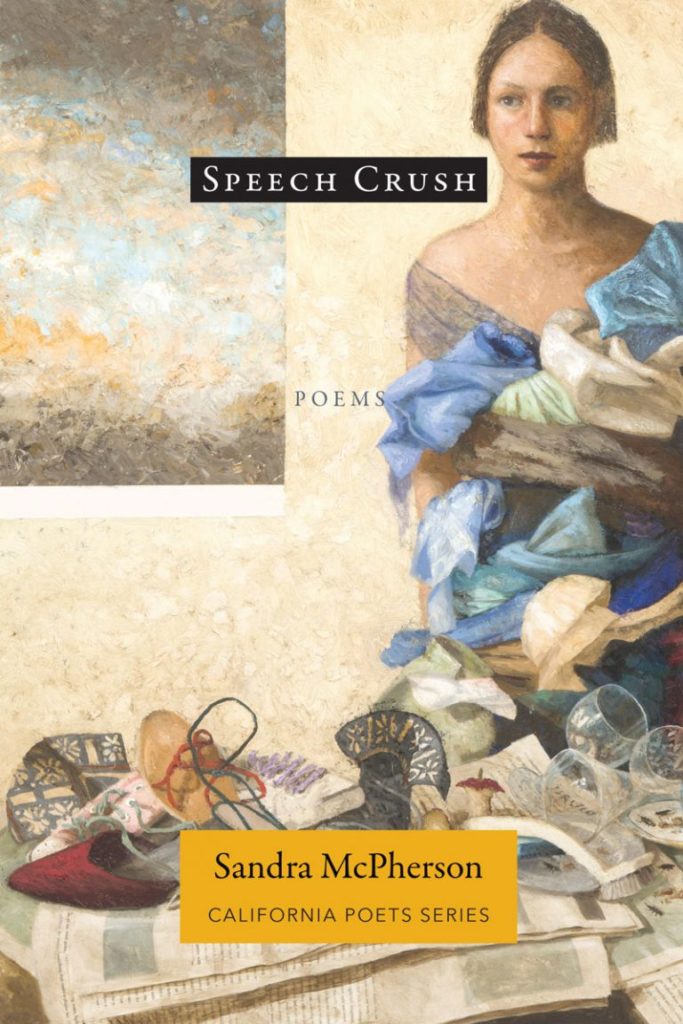

Nan Cohen (NC): I’d love to start by asking you about the cover image of Speech Crush, Katherine Ace’s painting Cinderella with Shoes. What’s the story behind the pairing of this painting with this book?

Sandra McPherson (SM): I’d love to talk about Kat Ace.

Around 2012, when I was suffering the beginnings of an old-fashioned “nervous breakdown,” Kat came through town and gave me a red suede-bound blank book. I used to keep journals regularly. I tied her notebook to my iron headboard so it wouldn’t fall off. I wrote brief jottings in it—speech that seemed hard for me at the time. It was no longer full confessional paragraphs; just brevities. A few years later they formed the first section of The 5150 Poems, which I had no publisher for until 2022. When Nine Mile accepted the finished manuscript, we chose Sharon Bronzan’s image of a woman balancing atop a tiger for the cover art. Sharon is a best friend of Kat’s. And Sharon has been my friend since before we were born, since her dad was San José State’s football coach and my dad was the basketball coach. Our dads played on the San José Spartans football team together in the Thirties.

I had long wanted book covers by both Sharon and Kat. If you look at Kat’s website, you’ll find a wealth of intriguing women and objects. This painting was the best compositionally to house the book title and my name. I love its warm colors and Chryss Yost’s design—clean, clear. There’s a poem called “Cinderella” in the beginning of the collection. The version in Speech Crush is slightly revised from the first time I used it in a book. Women of my generation no doubt identify with Cinderella; girls of today probably will have other movie and cartoon heroines. I don’t know the current mythology so I can’t guess how different their heroines will be from our Cinderellas!

NC: I strongly associate the woman in Cinderella with Shoes with not only the version of Cinderella in the poem, but also the speaker of many of these poems. With her steady gaze, her half-in-shadow face, and the array of objects before her, she seems to be presiding thoughtfully over a kind of arranged chaos. In this book, you have continued to write about the experience of breakdown, hospitalization, and recovery—you’ve even republished some of the individual pieces in The 5150 Poems. Can you tell us more about how the people identified as fellow patients came to mingle with the other important people you invite into this book—your parents, brother, daughter, your birth mother and father, friends, poets? One very specific question might be: why do you begin the book with “For Cindy, Who Cut Her Own Throat: Sutter Psych Hospital”?

SM: My fellow patients in 5150 were the key to regaining my health; I felt love, concern, for them—I felt familial with them. As I cared for them, my self-care grew. Thus, I could begin Speech Crush with Cindy and her harrowing self-harm and recovery; and I could follow Cindy with Eleanor Pavlich, my dear mother-in-law; and thirdly, Cinderella, the beautiful young woman who we all were at one time—the myth of us. Three short lyrics with women and our precious props.

“The Senses,” which comes next, tells a Gothic story of growing up on Poe and kissing a startled woman-friend on the mouth. Associations with other women follow, as I “act my age”—that is, O-L-D.

I began with Cindy, by the way, to be brave. To shock. Not to back off of the drama and trauma subsequent poems deal with.

NC: The poems in Speech Crush seem to turn both inward and outward. They grapple with both recent and past experience and often feel very interior, yet they also strive to connect with readers—those who have long followed your work and those who are new to it. The poem “New Friend,” for example, reflects both the pleasure of making a new friend and the complexity of opening up a long and complex life to someone who has just arrived in it! What do you hope your new readers will find in this book?

SM: “After Trauma” is a poem that seemed to mean something to readers when I posted it on Facebook after Ploughshares first published it. I’m wishing for that kind of thing—readers to connect—and why? And what does the poem offer them that no other poem has, maybe? It was very important for me to write it—and not for the reasons that may be obvious: I had actually had a traumatic experience not addressed by the poem. So I went “sideways.”

When I was young, there were anthologists my age who would select my poems to include—that was really helpful. Now, the anthologists are the young generation and probably do not read my books—I don’t know. Sandy McClatchy died; David Young retired; Oregon anthologists did both; etc. But my work in Speech Crush should be highly anthologize-able! I’m just really curious to know how Speech Crush reaches other lives, especially women’s, and aging imaginations.

NC: “After Trauma” reminds me that I wanted to bring up that, as well as being richly populated by people, this book is also a book of things—their strange persistence (as in “For Eleanor”), their loss, their lingering in memory. The cranberries, blackberries, blueberries in “After Trauma” feel so real, somehow. Their splashes of familiar color, their associations. They are a safe topic, in a way, but the poem also acknowledges that nothing is a safe topic, really. Cranberries grow in bogs, blackberries in brambles, blueberries in bushes—the “low mist” you hid in seems to seep all through the poem. Just such a beautiful evocation of the power of the past churning the present, and the present pushing ahead . . . I’m just musing here, maybe no real question yet. But something about the power of objects. The orange Nehi soda in “Birth Mother,” casting its long-ago shadow, the way you know the orange of it though the photo is black and white! Love that.

SM: That’s interesting! I wonder how many ways there are of people being with Things, or the opposite, revoking Things. I make a joke at the end of the poem where the FBI agents come visit me—do their wives collect anything the way I collect art? Walter [Pavlich] and I were in the antiques business just for fun, the way many people were once eBay came into being, to educate ourselves on history. My book A Visit to Civilization embraces the study of some of the objects that came our way.

NC: On the subject of ways of being with Things, or revoking Things—you mentioned wanting to know how Speech Crush “reaches other lives, especially women’s, and aging imaginations.” For me, I feel a very strong connection to the way objects evoke memories—it happens a lot in the poems, and it also feels like a subject of interest to the poems. Perhaps related to this, I’m also interested in that last phrase, “aging imaginations,” and what it means to you.

SM: Things: I recall being taught Neruda’s declaration that he loves “impure” poetry, full of Things. You might hunt for that page or so. [NC: Here it is.] And later I came to love Francis Ponge, his great poems about Things.

“Aging imaginations” . . . that sounds like a good koan for me to go to bed and meditate on. I think I’ve barely begun to learn about it. Just want to make sure that as our imaginations “age” I’m not suggesting deterioration—more like evolution. Section IV of the book starts with the 17-year-old and ends with “There is always more to solve.” These poems are my age, so to speak: “Spill,” “Pointed Question,” the elegies for friends, the trees of “Faith” keeping their promises. And, explicitly, “Last Conversations.” Immersion. Continuation.

Don’t you think we wish we could see what Plath and Sexton would have lived to write?

NC: Absolutely agree about Plath and Sexton. Do you happen to have read Eavan Boland’s last book, The Historians? There is a poem in it about Plath—“For a Poet Who Died Young.” She was 15 years younger than Plath—she wrote in an essay about the winter that Plath was writing Ariel and she—Eavan—was a college student. And the changing place of Plath in her imagination is what I’m drawn to think of now.

SM: Extremely helpful—reading the Boland poem I’ve begun to see how I’ve constructed a life-jacket for myself, this Old Woman! And much to my surprise it is constructed of Stories! I’m not a story-writer, but we all live stories and now I can see my lyrics as narratives.

Prior to putting Speech Crush together, I did some lifesaving in The 5150 Poems with its final poem, “Five Leaves Left.” It’s sort of a chain of things that made me want to live, after my suicide attempt.

NC: Thank you for pointing me to “Five Leaves Left”—my copy of The 5150 Poems arrived and I was able to read it. How beautiful and complex that “chain of things” is! So much sound, so much art, so much nature, so much ordinary life.

The life-jacket constructed of stories—what a wonderful image! Dimly I recalled, then went to find, Anne Sexton’s poem “Letter Written on a Ferry While Crossing Long Island Sound.” That poem seems like a good example of a lyric that contains or intersects with a narrative, as in so many of your poems. Do you think the relationship between lyric and narrative in your work has changed over time? Perhaps time naturally transforms a series of lyric utterances into a narrative, but do you have a sense of building narrative now that you didn’t before?

SM: It is natural for me to compose metaphor after metaphor; my daughter as she learned to talk also spoke in metaphor. See her poems in The Spaces Between Birds. But when I started teaching at Iowa I could see that certain of my students were good at narrative poems and that I wasn’t. Mark Jarman started a literary magazine that required a poem to have a story; another fellow was about to have a novel published, and he’d read my poems and pointed out their obscurity because I didn’t know how to tell a story in verse.

In Speech Crush I have plenty of “leaping” lyrics: the three Americanized ghazals are really good at disjointedness! They’re supposed to be. Say something and then leave it behind and say something unrelated and new. But when you come to the poems about Chef, a bipolar boyfriend I had after my husband Walter died, I try to narrate better: “Courbet is a Desperate Man” and the five “Springforms” sonnets. People aren’t likely to know what this man is doing, so I work to show it more clearly—once, for instance, he was hired to feed “giants”—the world’s tallest man and woman, who didn’t know each other prior and had this blind date.

I used to say I couldn’t write stories/fiction because I didn’t perceive events as having a

beginning, middle, and end. So [now in my current poems] I try to find those three phases, though they needn’t be in that order. “Last Conversations” is like a little anthology of stories—gives people a choice of chapters/experiences/roles lived together/summaries/evolutions, in the form of a little library of mini-stories. “Finishing” needs by its very subject to get from here to there.

Of the mental hospital poems you might say Cindy’s slashed throat poem is lyric leaping; but “Class Act / Art Class” is more linear narrative. It illustrates another important method I’ve been learning to use to narrate—dialogue. I’ve discovered that things my mother or brother, for instance, said to me hang in the closet of my mind for decades until I can see where they lead: “Quicksilver, Cougars, & Quartz” and “Pointed Question.” They hurt. The wound needs to start bleeding its story as my mother talks.

When not recalling people’s hurtful talk, I’ve borrowed stories I like from the way good poets use them—so I embrace the language of Gwen Head, John Dryden, Rilke, Roethke, song lyrics of “Tenderly,” John Ashbery’s quip “try selected whitecaps.” This speech makes the poems more story-like.

NC: You mention leaps and leaping lyrics—was Bly’s Leaping Poetry influential to you? Or is it more like a collection responding to a conversation that was in the air in the 60s and 70s?

SM: Leaping was in the air, as you say, before Bly’s book came out—but we were reading poets that he translated, I’m pretty sure. I was also trying to translate Spanish poets.

Three more thoughts for the moment: “On Your DNA” is a leaping lyric; “Simple Science” knows its beginning, middle, and end because it’s about falling in love with the man, getting married, and his dying. And “Spill” and “Runneth Over” are prose poems—really prose ghazals—starting with story and leaping about later; that technique helps me find different ways of narrating—my last few books utilize the prose paragraph.

NC: Since you mention Gwen Head and Theodore Roethke, could we touch on your relationship with that magazine and with the Pacific Northwest? You lived in Seattle, and Portland. You mentioned beginning to publish in Poetry Northwest, first with Carolyn Kizer as editor and then David Wagoner, and that your friends Joan Swift and Gwen Head published there as well. I’m curious what stands out to you when you think about those years.

SM: It seems to me that Dave Wagoner read aloud to me Gwen Head’s first poems published in Poetry Northwest, just slightly earlier than he published mine. I was wowed. They became examples of the way I’d love to write—full of surprise words and unusual action, urgent. I don’t know what influenced her—she was just a beginner but sounded utterly confident. The three poems Carolyn accepted [published in the Autumn 1965 issue], I wrote as an undergrad at San Jose State; Carolyn accepted them when I arrived in Seattle. I didn’t know about Gwen Head until about a year later.

Later than that I was impressed and influenced by Joan Swift’s rape poems. After this horrible crime, which occurred in the Bay Area, she wrote the rest of her lifetime dealing with it. She moved from what she thought were too prettified metaphors to trial transcripts, brutal and shocking. Nonfiction. Gwen started a press, Dragon Gate, which published a batch of the rape trial sequence. It was the truth-telling and bravery that touched me most—I had not had such a terrible experience myself.

NC: “Truth-telling and bravery” describes your own work, too. In this book, as throughout your work, you have reckoned with family, art, womanhood, motherhood, despair, joy. What are you reckoning with in the poems you’re writing now? And has the way you work changed?

SM: I think I can reveal something about my current way of working. The Georgia Review will publish “Breakfast Over Ikutaro” sometime this year; it derives from my studying Japanese artists rather by happenstance on Facebook. I spend every night in Japan, using a translation device called DeepL. I’ve been doing this for over a year. I’m fascinated by the lives the artists reveal. Some of these people are photographers, potters, there’s one mime, fine woodworkers, textile experts, cartoonists, Butoh dancers, tea masters, haiku practitioners, drunkards, ikebana masters, and everyone seems to cook up beautiful meals which they photograph. They’re child educators, wildlife experts, museum curators, calligraphers. Farmers. They love bugs and take exquisite close-ups of them. Me: I’m the learner.

–

Sandra McPherson has twenty-two collections published, including 5 with Ecco, 3 with Wesleyan, 2 with Illinois, 2 with Ostrakon; 1, The 5150 Poems, with Nine Mile Books; and 1, her newest collection, Speech Crush, from Gunpowder Press (Santa Barbara, CA). Starting with early work published in Poetry Northwest, her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, TriQuarterly, Pedestal, Field, Poetry, The Iowa Review, Yale Review, Agni, Ploughshares, Kenyon Review, Ecotone, Cimarron, Nine Mile Magazine, Crazyhorse, Basalt, Cirque, Plume, Red Wheelbarrow, Epoch, Willow Springs, Vox Populi, Whitefish, Michigan Quarterly Review, Antioch Review, and many more. She taught for 23 years at University of California at Davis and 4 years at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her collection of 67 African-American improvisational quilts is housed at University of California at Davis Design Department. She founded Swan Scythe Press. She is the great-grand-niece of Abby Morton Diaz, Plymouth feminist author and abolitionist. She was married first to poet Henry Carlile, and subsequently to poet Walter Pavlich.

Nan Cohen’s books are Rope Bridge; Unfinished City, winner of the Michael Dryden Award from Gunpowder Press; and a chapbook, Thousand-Year-Old Words (Glass Lyre Press, 2021). Recent poems and prose have appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, Electric Literature, RHINO, and Tupelo Quarterly. The recipient of a Wallace Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University and a Literature Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, she co-directs the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference poetry programs and lives in Los Angeles.