Interview // “Shapeshifting, Flawed Mediums, and Wolves”: A Conversation with Jessica Q. Stark

by Alexa Luborsky | Interviews Editor

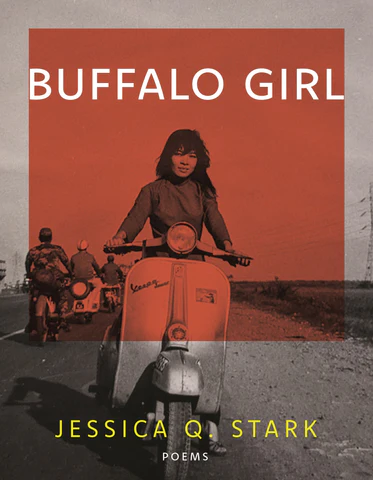

Jessica Q. Stark’s Buffalo Girl reconstructs the aftermath of diaspora through ghosts, fairy tale, and collage. Stark’s flowers and woods tower over the characters in her poems, threatening to consume the narrow path walked by the speaker, mother, and the many iterations of Little Red, towards a wolf; be it a wolf of violence, of diaspora, or of hunger. Stark incredibly, even in the dense forests of her language, does not allow the reader to make a spectacle of her ghosts or of diaspora more generally. There is no ending to the trauma of diaspora and thus there is no ending to this collection. This is a collection of retellings, of collaging the historical with the present, of refusing to make a neatness out of something that is messy and complicated. I was so grateful to be able to speak with her about her beautiful work via a Google Doc.

*

Alexa Luborsky: Firstly, thank you so much for speaking with me about Buffalo Girl. I’d love to start out by talking about spectacle and survival, because I think it is central to how you think about finitude, and has to do with how you were maybe bridging your first collection, Savage Pageant, with this one. In a previous interview with Tarpaulin Sky about your first collection you said:

A spectacle must also end, which this book does not. Like I mentioned, the first poem in this book is a bridge, which considers a more personal plight of my own survival as being the offspring of the American War in Vietnam and the monsters that diasporic experiences create for show and for survival. I guess it’s always been about survival.

You also said of spectacle in this interview that: “A spectacle relies so heavily on a neat ending that gives you good feelings or makes you feel like you’ve learned something that you already know.”

I’d love to hear more about this from you in the context of fairy tales, namely, Little Red Riding Hood, which is central to this collection. Fairy tales often are driven by a “moral.” They also rely on archetypes, on categorization, on neatness, which I just think you are not interested in as a writer. In these poems the wolf isn’t a neat villain and Little Red is not a neat victim. Each informs the other. I am thinking as I read about how “victim” and “hero” are such fraught concepts in the context of diaspora. I mean this both in the way that people who are not directly involved in war will make a spectacle of a victim and also in the way that we, as writers who are descended from violent diasporas, reference our own dead. I’m also thinking a lot about how there is a performance of survival that we write, whether in the context of war and diaspora or not, and how that is then consumed by others. There is a lot of hunger in this book too. So, in addition to the fairy tale lens, I’d also love to hear your thoughts on survival, consumption, and spectacle, and more on how it bridges this collection to your previous one more generally. Lastly, do you think that there is a way to write about diaspora that is not in itself violent? This last one is a kind of selfish question because I think about it a lot in my own work!

Jessica Q. Stark: Thank you so much for this rich question, which contains so many shadows I barely know where to look to begin answering it. I’ve thought incessantly about the ethics of writing about and around violence in history. I can’t get out from under it because it is such a vexing issue. I explore this in my first book, too, though the fixation is different there. Relatedly, to write one’s existence, one must inherently unfold a story that invites consumption. I am troubled by the potential palatability of this meal. And to your point: yes, I am interested most in resisting neatness because we are not a neat species; I am not a tidy person. However, I don’t mean to sound like an elitist, mulling over some language that only I know how to speak. I want the importance of these stories to be accessible, tactile. But the book is such a flawed medium, isn’t it? It’s so arrogant, like any container. And to write truthfully I feel I must invite some occlusion, some deep failure to contain it all. When writing Buffalo Girl, I wanted to embrace and trouble the boundaries around different categories: hero/villain, information/gossip, truth/misunderstanding, audience/writer, image/poem, poem/trash. I’m very nauseated by my own impulses to desire and conform to these categories, to live by them, to remember personal and national histories within their supposedly fixed power dynamics. I want to be clear that I am not absolved of these tendencies to define and restrict and embellish. However, I tried very hard to let my own self-doubt of my memory of my mother leak into this book. As a way to challenge the hard line of storytelling and craft and easy consumption.

This book started with a photograph that I found of my mother when I was very young. I have included it in this book and I have included the vital, accompanying feeling that there was a part of her life (of her being) that I could never fully intellectually access. And that feeling was accompanied by a feeling of liberation, rather than disappointment. A spectacle can never feel truly liberating because it is inherently knowable and placating. Whether I fail or not, I want to resist the tendency to provide difficult narratives through a lens of spectacle; a lens that simply indulges our limited, human desire to know everything. I think this might make my books boring, which is an important feeling, too. I think that boredom is vital for me in framing these stories that so often involve violence and the messy bits of existence. Boring means that it still is a significant part of everyday existence. Boring means we must carry it around and take it out for a walk. I don’t want to close the book, clear the plates. To me, inheritance and debt and violence are always unfinished business.

AL: Many of the “after” poems that reference flowers are called “liberal erasures” in your notes section. This phrase, “liberal erasure,” offered me something I wanted to cling to as a kind of anti-deportation from the binary of “in” or “out” inherent in the nature of diaspora: stay or go. Stillness or movement. In “Red Encounters a Stray Bullet at the Marketplace,” the prose-poem ends with: “What cannot end at the end of this story? [Everything] She knows the route by heart, but my, what a pretty flower.” This “route” to me is of course the route in the story of the traditional fairy tale, literally and figuratively, but it is also the deportation route, the route of diaspora.

The interjection of the flower feels like a breath to me. Where everything else is cycling, the flower is a brief intercession. In “On Passing,” there is a litany of ifs, the concluding one being: “If she could stay still.” I take this “she” to be the speaker’s mother in Vietnam. The Little Red of “The One in Which the Wolf Wins” is said to have:

loved a simple, beautiful

flower more than herself,who trusted everything,

except her nose and

eyes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This feels in line with this complication of in or out, stay or go, the violence or non-violence of origin, of language, of place, of woods maybe. Can you talk to me about flowers, the woods, stillness for someone who has inherited the movement of the diaspora, home/womb, woods, and self in this book? If both movement and stillness are violent in their own ways, what movement is left? Could it be the circle, or put in a more literary term, the lyric, which neglects both maybe by embodying a part of each? What is this hybrid space?

JQS: I think you have locked into the challenge of this book, which is very much at odds with linear movement. As this book is so fixated on memory, recursive movement was key to its development. I wanted to think about how my mother came before it all–of my existence obviously, but also before the development of a war, before Little Red Riding Hood, before ancient women warriors in Vietnam. I wanted to rethink the vexations of lineage and time and I wanted to upend them in language. And in so doing, I wanted an alternate form of movement that challenges a conventional understanding of history as serial, as linear-progressive, as in lock-step. This is really just a form of wandering, which I punctuate with flowers in this book to parallel my own curiosity, my mother’s curiosity, to the curiosities of one thousand Little Reds that came before and after us as well. I live in Florida and in this subtropical climate, the foliage here feels violently alive. The flowers and invasive vines are so beautiful, but everything feels like it’s breathing, as if the plants are poised to reclaim the land if we were to briefly turn away. I was attracted to this feeling of both fear and deep awe and I felt it had everything to do with my relationship to my mother, to history, to the conditions of my existence.

AL: I’d love to hear more about how you thought about “ownership,” “theft” and “bartering” in this book, especially in the context of the series of poems titled “Kleptomania” and a year, as well as the central figures of Triệu Thị Trinh and the mother in this collection among other complicated female figures in Vietnamese history. Ownership, or lack thereof, feels very complex in this collection. There is so much bartering in this work for that which could feel, to some people, as “givens.” In “Poem in Which I Narrowly Escape My Birth,” we see:

Bleached poem about the

broken jade bracelet my

mom hid in the front ofher underpants on a

helicopter for which

she bartered a broken fairytale. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The mother here is further likened to Little Red:

know a traveling girl with

a basket never keeps thebread or wine. She

loses her talons for a time and

forgets the image of hergrandmother’s face.

I’d like to bring this bartering in proximity with the bartering of “Kleptomania, 1993”: “On the / other side of the world, you learn / how to haggle.” This “you” seems to me to be referring to the women who:

mostly do it or at least

are more punishable for the

crime of taking what’snot rightfully theirs.

This sense of how forced diaspora creates a violent disjunction between ownership over place, over body, over home, such that everything else becomes tenuous for, not only those forced from their home, but also for the children and grandchildren of this forced movement, including the relationship to the pain from this loss of home and inheritance, which has to be “negotiated.”

The questions from the first poem titled “Catalogue of Random Acts of Violence,” to me, are a representation of that negotiation. Can you tell me about how you envision the speaker negotiating diaspora, how these complicated female figures might represent a turning away from this type of negotiation and maybe further towards ownership of the past in terms of identity, and how this collection might be more interested in rebelling against the notion of a happy ending in the context of diaspora as a way of resisting spectacle? I’ll note the epigraph of the collection here: “no one knows who one is / and the texture of knowing this / doesn’t feel human.”—Justin Phillip Reed, Indecency.

JQS: Thank you for this insightful reading and for pulling out parallels in the book. In that poem you reference, “Catalogue of Random Acts of Violence,” is an accumulation of questions that are, at their base, obsessed with categories and purity. I’ve received and responded to these questions at one time or another, often repetitiously, from well-meaning acquaintances or strangers. I understand the questions are couched in curiosity, usually from someone that doesn’t quite understand how oddly taxonomic these types of inquiries can feel to a mixed-race person–especially when they accumulate over time. I think the echoing poem on the next page, a repetition of words “The Woods” in response to each line of the previous poem, is more in line with the kind of negotiation that you mention in your question. Which is to say there is no negotiation; there is a turning away.

To elaborate: I’m interested in the woods and its history in literature and folklore as a place of great danger, but also as a home for foxes and outcasts that provides protective obscurity and provocative indistinction. I’m also drawn to it as a nebulous place that both affirms and eludes fixedness and an intimate familiarity. You know what I mean when I say “woods,” but your image of it varies (likely wildly) from mine depending on your own personal history, the woods you’ve been in in your lifetime, maybe your socioeconomic class, too. It works as the Little Red Riding Hood story, in this way. That this old story feels so known, despite there being hundreds of permutations of it with dramatic divergences and alternate endings. This sometimes feels like the only way to respond to taxonomic questions; a reminder of the woods.

AL: I’d love to end by talking about ghosts and the collages in this collection, which feel like they’re orbiting each other and collectively haunting these beautiful pages. The black and white photos, in addition to the cover image, are noted as belonging to, as well as depicting, your mother. There are also Little Red illustrations, which are credited to Walter Crane. There are no captions on these images, which gives them a liminal spatial feeling for me as a reader when I encounter them beside a poem because they do not bring their own contexts with them. They arrive in an extratemporal, extralinguistic way. They are therefore, in these ways, ghostly. But I’d like to be careful in how I use that word. To that end, I’d like to bring up something you’ve mentioned previously about ghosts in an interview:

My mother is Vietnamese, and for Vietnamese people, death is, in Buddhist culture at least, celebrated to some extent. We celebrate a loved one’s death day each year, for example. I feel like Vietnamese people love believing in ghosts—I believe in ghosts—which in my mind isn’t in the same way as in American culture, which is always related to sensational terror. Everyone is mostly terrified of death.

Ghosts are given an important agency in this work it seems to me which is not often given. In the collages, the male figure who is typically physically erased by images of woods and plants in the collection yet maintains an outline, as does the wolf, is I believe ông ngoại, the maternal grandfather figure. The mother, and Little Red, in terms of their bodies, are not overlaid with anything in these collages. Plants and trees bloom around them but not over them in the same way. In “The Furies” you write: “That Eurydice was never asked where she’d prefer to stay / That the woods obscure as much as they protect, that at least you can lay there.” And in the final poem, we get: “Violence is my pelt, my light fanged hoof. / When I was girl, I haunted men.” To me this represents an interesting connection between haunting and consumption. Maybe even consumption via the shade given by the towering, ever-present, ghostly figure of the woods in this collection. This is all to ask, is hunger the real ghost-figure of the work?

JQS: Ghosts, like so much in this book, shapeshift, as you’ve noticed. When I was writing this book, I was obsessed with ghosts in the way my mother has always been obsessed with ghosts. Abstractly, I think ghosts can be these strange receptacles for shared anxieties around inheritance and danger and surveillance. Concretely, not all ghosts are treated with kindness in this book. In response to the moments you signal, there are some ghosts that I wish would scamper off, that have become a house nuisance even though they are no longer scary. For example, I was interested in erasing popular versions of the story of Little Red Riding Hood, to find the little ghost girl hiding and to draw her out from under all those hands, that language. To let her desire, to let her look around.

And there are the ghosts of my ancestors who I know only through my mother’s stories, her rumors, her memories retold. There were a number of rumors of hauntings that permeate my mother’s memory of family members haunting other family members post-mortem. I became interested in how ghosts, realized or as a concept, are tethered to cosmic retribution and undigested histories in this way.

But there is another kind of ghost, which I think has more to do with your attention to hunger as the real ghost-figure in this book. I’m very interested in thinking about money as perhaps the ghost behind many ghosts in my work. I’m fascinated in thinking about money as an apparition whose haunting drives earthly creatures to do the silliest of actions, to become the strangest renditions of oneself. Every single person I know, including myself, is haunted by this not-love, this not-woods. I’m just trying not to feel hungry anymore for this kind of haunting, which begins to feel like a part of one’s skin.

—

Jessica Q. Stark is the author of Buffalo Girl (BOA Editions, forthcoming 2023), Savage Pageant (Birds, LLC, 2020) and four poetry chapbooks, including INNANET (The Offending Adam, 2021). She is a Poetry Editor at AGNI and is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of North Florida. She co-organizes the Dreamboat Reading Series in Jacksonville, Florida.

Alexa Luborsky is a writer of Western Armenian and Eastern European Jewish descent. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in journals such as AGNI, Black Warrior Review, Guernica, and West Branch, among others. She was runner-up for the 2022 Quarterly West annual poetry prize. Currently an MFA candidate in poetry at the University of Virginia, she is the Interviews Editor for Poetry Northwest and reads for Meridian. You can find more of her work at alexaluborsky.com.