Interview // Searching for Home, Connection, and Place: A Conversation with Ruth Dickey

by Gabriela Denise Frank | Contributing Writer

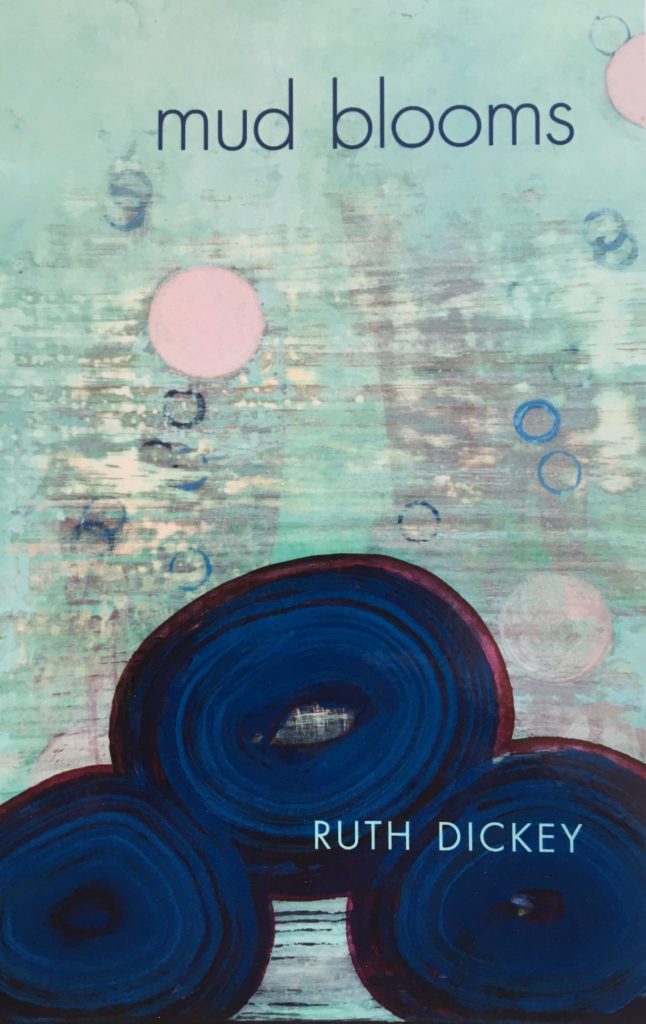

Ruth Dickey is a poet, community-builder, and a devoted fan of apple cake. For the past eight years, she has served as the executive director of Seattle Arts & Lectures; this May, she will join the National Book Foundation as its executive director. In November 2019, Ruth published “Mud Blooms” (Harbor Mountain Press), her first full-length collection of poems. She is currently at work on two book-length projects: a volume of poems about healing from the pain, shame, and stigma of queer divorce, and a book of essays about her pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago. Ruth and I spoke several times this past fall and winter—via Zoom, by phone, and over email—about the ways in which we are all searching for home, metabolizing grief, and attempting to make sense of a world in the grip of a global pandemic.

Gabriela Frank: Mud Blooms weaves together your experiences teaching poetry in a soup kitchen in Washington, DC; memories of North Carolina where you grew up and where your mother passed away; and travels through Latin America where, as a young woman, you explored the boundaries of yourself. How did these threads come together?

Ruth Dickey: All of the threads are about hunger and a search for home, connection, and place. At Miriam’s Kitchen, an organization dedicated to ending homelessness in Washington, DC, I ran a writing workshop after breakfast every Wednesday for seven years. The only rule was, everybody writes. We sat together at that table as peers trying to figure out how to put words that mattered on the page. It was an amazing experience.

I wanted to honor the men and women I met through Miriam’s Kitchen and help readers understand how traumatic the experience of homelessness is—as are the systems that both create homelessness and, theoretically, support people in finding housing. It was important to me in constructing the book that these stories were interwoven and talking to one another. I didn’t want the stories from and about Miriam’s to be separate from my own story.

The construction of the book is very much like the experience of that after-breakfast writing workshop: trying to figure out what home means, how to make sense of the world, and how to grieve. That’s why the poems ended up being organized the way they are. An abecedarian poem called “Alphabet Soup Kitchen” arches throughout the whole book. These teeny vignettes are my attempt to capture the richness and complexity of Miriam’s Kitchen and the people I knew there.

GF: You wove writing that resulted from the workshops into the titles of your poems. Can you talk about that process?

RD: The lines that appear as poem titles had previously appeared in 167 Wednesdays, 167 Thursdays and Soft Concrete Stairs, two anthologies we published at Miriam’s Kitchen, which were made of poems that people wrote after breakfast. In Mud Blooms, they work as persona poems. I wanted my poems to include voices from people at breakfast, and I was thinking, How do I re-enter and find those voices? That’s really where it began.

GF: When you say you were examining what home means, what were you looking for?

RD: The poems in Mud Blooms span more than twenty years of life, from my twenties to late forties. Through those years, I lived in DC (twice); New Orleans; Greensboro, North Carolina; Seattle (twice); and Cincinnati, Ohio. Through all of that, I had been thinking deeply about what home meant and what it means for any of us to find community and our place in the world. My wondering about home was intensified by my time at Miriam’s Kitchen where I got to know so many people experiencing homelessness. It made me think deeply about the systems and conditions that contribute to people not having access to adequate housing, health care, support, and living-wage jobs. All those questions are bound up together. For me, the most honest way to approach answering them was to ask them of myself as well. Throughout the book, I’m trying to find my way by witnessing their complexity in search of deeper understanding and peace.

GF: Are there specific poems through which you came to a moment of understanding or epiphany? What becomes clearer as you revised the collection?

RD: Absolutely! The trio of poems titled “Somoto, Nicaragua” is about understanding my privilege as a white woman with U.S. citizenship capable of traveling and living in Central America. The same is true with “Mercado, San Cristobal de las Casas, Three Sonnets.”

The poems “brown shirt” and “87 days after she found a lump” are about understanding that my mom was seriously ill—she had cancer—and might die. I was initially oblivious to that, then utterly broken open by it.

“The letters, 1” is about a violent incident I experienced and the ways in which naïveté and good intentions can be insufficient and even dangerous. “The letters, 2” is an erasure poem from letters that I write to my mom every year on the anniversary of her death. It’s a gesture toward metabolizing grief and the redemption of hope.

It became clearer to me as I revised the book that living in this world is desperately painful and yet beautiful. Ultimately, I do believe deeply in the power of hard-fought hope.

GF: Mud Blooms is powerfully observed and visceral. Food of all kinds is woven through—apples, apple cake, milk, honey, nutmeg, nachos, champagne, eggs, smoked salmon, capers, lemon wedges—as are themes of hunger, desire, and shame. Are these subjects central to your work as a poet, or are they specific to this book?

RD: As a queer woman and someone who has spent over two decades working at the intersection of community-building, art, and social justice, I’m deeply interested in hunger, desire and shame, and in how the decisions each of us makes impact the larger world. I’m interested in poetry of witness and poetry that is political and narrative, so I’ve written a lot of bad didactic poetry over the years. (I wish it weren’t true, but that’s been an important part of my learning journey.)

My hope in my writing is to dive into the personal as a way of understanding and saying something that is larger than an individual experience—to tap into the idea that the personal is political. Food is a particularly rich subject because it’s so linked with how we build community, show love, and nurture each other, and it’s inherently political when we consider who has access to a range of food choices or who is physically proximate to grocery stores. On a personal level, food was how my family showed love (apple cake makes a star appearance in the book). My mom struggled with her weight her whole life; she held a lot of guilt and shame about that. I could probably spend the rest of my life thinking and writing around these issues and still find more to explore.

GF: The book’s title comes from the last line of the last poem, “Take deep breaths / hold a pen / sit still.” How did you come to that title to pull this book together?

RD: The last poem is really a prayer for the Miriam’s Kitchen poets and for any of us who are searching for home. It’s about the ways in which their lives are sacred. Our society depersonalizes and devalues people experiencing homelessness, and I wanted everything in this collection to fight against that. To me, it’s finding beauty in things that traditionally aren’t seen as beautiful. That’s why the last words are “blooming mud.”

GF: Where is the chapter of Mud Booms on the longer continuum for you?

RD: This book had a strange journey into the world. About ten years ago, an earlier version was going to be published, then the small press went out of business. It totally fell apart, and I put it in a drawer. I thought, Okay, done with that. I’m not doing poetry. Then I came to Seattle Arts & Lectures (SAL). Having the privilege of hearing writers read their work and hearing young people read their work was super inspiring. I thought, I cannot do this work without also struggling with my own writing. Part of authentically showing up in this job is showing up on the page—and succeeding and failing and carrying on—so, I got the manuscript back out. At that point, I had lost my mom, and there was a different depth to the poems. The book wasn’t succeeding the way it was, so I layered in more things to make it cohesive. It’s a different book now than it was then.

GF: You’re currently working on two projects: a manuscript of poems and a prose project about walking the Camino de Santiago in Spain. Can you talk about the themes driving these books?

RD: For better or for worse, my writing comes from the messy middle of my life and the things I’m struggling to understand or make sense of. The manuscript of poems is about the particular pain, shame, and stigma of queer divorce, and I hope it’s also about healing. The Camino project is about my literal pilgrimage, but also about the idea of transformation through doing something that feels almost impossible. I’ve never tried to write extended prose in this way, so to me the writing project also feels almost impossible. I’m failing and learning a lot, which has been wonderful. At this time when we can’t travel, it’s been a gift to spend time deeply thinking about being somewhere very far away.

GF: In 2020, COVID has profoundly disrupted the work of arts organizations, which rely on in-person events, performances, and gatherings. From an audience perspective, SAL has reacted nimbly to these large-scale changes. This is no small task. Can you talk about what you’ve done as an organization to keep going, and what you foresee happening in 2021?

RD: Let me begin by saying that I’ve been incredibly lucky to work with the most talented team of intrepid, creative, resilient humans on earth. SAL is fortunate in that the type of programming we present—an author on a stage speaking or having a conversation—translates well online. We have been able to continue with a full season in the digital world. The toughest part is that we’ve had to re-imagine every element of our events and learn rapidly about the technology to do this, what support we need, and what support authors and audience members need. That’s been a huge learning curve.

There have been some incredible bright spots. Getting to see authors’ homes and writing desks has been a joy, and we’ve been delighted to have people join us from around the region and around the country, which wasn’t possible before. We’ve heard from many audience members who did not attend our events before because of geography or access issues that online events have allowed them to join us and provided a more welcoming experience. Truthfully, people had asked us for years to stream our events, and the pandemic forced us to innovate and figure out how to do that. Going forward, we will always provide an online option, even when we can gather in person—that’s an innovation that will carry forward.

GF: What challenges and adaptations do you see happening in the nonprofit world in response to the pandemic? What inspires a sense of hope going forward? Are there any aspects of “business as usual” that the pandemic has helped SAL to let go of?

RD: There is so much innovation happening, and a shared recognition that we are all in this together. Our poetic and nonprofit landscape needs all of us—a whole constellation of writers and artists and organizations. I love the direct support initiatives for artists that have begun, from the Seattle Artists Relief Fund launched by Ijeoma Olou to Shade Literary Arts’ Queer Writers of Color Relief Fund and Artist Trust’s COVID-19 Relief Fund. I love the way that organizations are supporting one another and drawing together, locally, regionally, across the state, and nationally.

At SAL, we’ve been meeting monthly with peer organizations around the country for solidarity and commiseration, sharing what we’re learning and what’s working (or not working), and that energy of connection is incredible. This moment has forced all of us to get comfortable with failure and things going wrong, and then learning and iterating, which is a terrific approach, even when it’s not a pandemic. These things give me hope that we will all become more nimble, more just, more welcoming, more accessible, more collaborative, more creative. The huge gift of things totally unravelling is that we get to imagine a new way forward together.

GF: Lastly—and with a twist of bittersweet: congratulations on the tremendous honor of leading the National Book Foundation! Can you share a few parting thoughts from the past eight years at SAL? What are you taking with you, and what remains?

RD: Thanks so much! It’s been a joy and an honor to work with the incredible team at SAL, and the phenomenal community of readers and writers and thinkers here in Seattle. I’m so profoundly grateful to have gotten to learn from so many writers, both the writers we brought to Seattle and the incredibly talented writers here in our community. I’m taking with me admiration and respect for our Pacific Northwest corner of the literary ecosystem and a heartfelt appreciation for the many people and organizations that make it thrive: independent bookstores, libraries, publishers, journals, organizations both formal and informal, writers, and tons of passionate booklovers, all of whom come together to make Seattle a special place for readers and writers.

I’m taking lots of things I’ve learned here, including how to be a literary citizen through lifting up the work of writers, which I’m excited to continue doing on a national level at the National Book Foundation. And I’ve learned the important work (and fun!) that can only happen when we collaborate, like Seattle being named a UNESCO World City of Literature or Independent Bookstore Day or Summer Book Bingo. Most important, I’ve learned ways in which our literary community has and I (as a white, cis, queer woman) personally have ongoing work to do to create organizations and systems that are anti-racist and that nurture belonging for all, particularly for people who have historically been marginalized and excluded. I’m taking with me gratitude for all this work and learning, and an ongoing commitment to continued work and learning—and a heartfelt promise to return to visit often!

—

Ruth Dickey’s first book, Mud Blooms, was selected for the MURA Award from Harbor Mountain Press and awarded a 2019 Nautilus Award. The recipient of a Mayor’s Arts Award from Washington, DC, and a grant from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, Ruth is an ardent fan of dogs and coffee. Since 2013, she has been the executive Director of Seattle Arts & Lectures, and in May 2021, she will become the executive director of the National Book Foundation.

Gabriela Denise Frank is a Pacific Northwest writer and editor. A Jack Straw Writer, her work is supported by 4Culture, Artist Trust, Centrum, the Civita Institute, Mineral School, and Vermont Studio Center. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in True Story, Hunger Mountain, Bayou, Baltimore Review, Crab Creek Review, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She is working on her first novel.