Interview // “On the Verbs of Looking”: A Conversation with Caitlin Roach

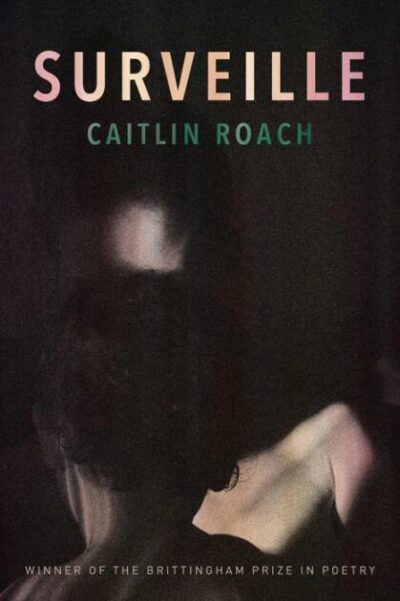

Caitlin Roach’s debut collection SURVEILLE, won the 2024 Brittingham Prize in poetry and was published by the University of Wisconsin Press. It is a swirling collection that sifts through the rot of political justifications and deconstructing the violence working through reproductive responsibility to care; Roach’s syntactic spirals expand an attentive collective consciousness that is alive and aware, and articulated in lines that simultaneously tighten and unravel the seen and the unseen. Zooming in on the faults of various power structures, SURVEILLE explores motherhood through a language of lattice work, eco-echos, and the gravity of our current climate, asking the reader to see what is necessary for the next generation.

*

Katie Johnson (KJ): Thank you for talking about SURVEILLE with me today; it’s really such an intune and timely collection. There were so many through-threads, kinds of ties; some of them loose, and some of them tighter. I was fascinated by this web of epigraphs, references to different quotes, names, and each of these individuals having different occupations, different geographical locations, origins, modes of speaking. And so, thinking back to the title, what does “surveille” mean to each of these voices and how does this verb take hold of this collection?

Caitlin Roach (CR): There are several modes and lenses of seeing in the book, and there are also many voices within it. Most of the subjects and themes across the poems are concerned with various forms of control and violence, and the scopes of intimacy of those violences—ranging from natural to self-inflicted to state-sponsored. A constant among the poems is an obsession of keeping close watch through those scopes—toward the self, the body, the lover, the state, the natural world, an unborn child. Of course, careful observation can quickly veer into surveillance. One can observe closely, which is rooted in concern for oneself or another, or one can surveil, which stems from paranoia or fear and is inherently a violation. Attendant to fear is threat, and I think a tone of threat lurks in many of the poems, even in the ones that feel quite private. Surveille (with the less common spelling, at least in American English), felt like an apt container for these various scopes of attention and scrutiny in both intimately private and public spheres.

That the title is a verb felt important, too. I liked the idea of it being an active, kinetic thing. And that, in the act of reading them, the reader would be doing something to the poems, acting upon them or their subject matter at the same time that the reader is being watched. Berger refers to this as the reciprocal nature of vision. The speaker of these poems is not only a subject of surveillance but also an agent of it, and I felt like the verb surveille had its finger on that relation of control that’s under tension in the poems, and on the relationship between a text and its reader which is always under some kind of tension.

But the title came really late in the game, just before it got picked up for publication. My dear friend, the brilliant writer Lisa Wells, gave me notes on a later version of the manuscript. I mentioned I was open to title suggestions if anything came to mind. The manuscript tried out a number of titles over the years, most of which were related in some way to ideas of recording, observing, or watching, but none of which felt right. She came back with Surveille. That did feel right. So the title was actually a gift!

KJ: I really got that notion as a reader, this underlying sense of survival, it felt very inherent. The duality of feeling a violent silencing, but also what the pull to understand, to feel safe in that environment causes in someone, for someone. A desperation that can originate and also become an invasion of privacy, as a wanting to help, to save, to remain.

CR: Desperation feels congruous as an experience or feeling across these poems. A desperation to become a mother, to protect oneself, to protect one’s unborn child from the very life you desperately want it to have, to reconcile the violence and hostility of the world. With such desperation to protect, concern can quickly become informed and guided by fear or paranoia, which is murky water the speaker treads in. Eventually, the distinction between observation and surveillance dissolves.

KJ: I was thinking, with regards to the title, to the many drafts that the collection went through while reaching towards its final stage, about the different voices in particular, the epigraphs as well, how were they excavated over time? What is the guiding conversation and/or force?

CR: I’m generally interested in the social relationship between a text and its reader and the way meaning multiplies or changes within that relationship. Polyvocality in a poem, in the particular context of reappropriating found language, is something I find really interesting, specifically in how casting the language in a new relational context can generate and reveal multiple layers of meaning. Authorial intrusion or exertion of this kind can feel aggressive in nature and I admire that.

In these poems, my language is frequently in conversation with others’, and often it was the moment of encounter I had with that language that occasioned the poem. So for the most part, the multiplicity of voices emerged organically. In poems like “The Inheritance of Intelligence” and “On Christmas Eve,” for example, I knew when I was present at the recruitment presentation from John O. Brennan, or when I encountered the language from Barack Obama, or Vicki Divoll, or former U.S. drone operators, that I wanted to respond to it.

The book epigraphs came later. My husband, the essayist José Orduña, turned me on to Annie Dillard, who instantly became a lodestar. I think the epigraph by her speaks to the subject-and-agent roles that the speaker of the poems occupies simultaneously.

Alphonse Bertillon was, depending on the account, a French anthropologist, police officer, and/or biometrics researcher in the early 20th century who invented the mugshot. He developed a system of indexing criminals using photography and physical measurements, which today we call biometrics. His indexical methods were eventually supplanted by fingerprinting and he’s often considered a forefather of surveillance. I find Bertillon fascinating as a historical figure, but I also like that the reader doesn’t need to be familiar with his biographical context in order for the idea of the reciprocal nature of vision or Merleau-Ponty’s idea of the primacy of perception—both of whom succeeded Bertillon—to be illuminated. Berger has said the same thing in different words: “The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe…We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.” The Bertillon epigraph doesn’t explicitly announce itself as related to surveillance, though it is. I like that it can be read in more than one way.

KJ: Yes, especially with the Bertillon epigraph, I actually had to read it 3 or 4 times, and each time I read it I found something different to grasp on to. That kind of attention opened up another way of seeing for me. It was here that I began to also think about uncovering within the margins of your poems. I was thinking a lot about white space, and I was so fascinated by how the form of poems like “At the Window” seemed to be stretching farther towards the end of the page compared to poems like “Witness Statement” which were a lot more clipped and cut with intense enjambment. I was curious about your interaction with white space and form in tandem with multiplicity in your poetics?

CR: Borders and militarized zones are recurring subjects or motifs in the poems, and many of the poems interrogate the permission and restriction of movement. I was often aware of some kind of constraint or control being exerted socially and politically when I was working on this book, as I am

still aware. And I was often among militarized zones and hyper-surveilled spaces, like the US/Mexico border wall, or along the perimeter of Creech Air Force Base, or at Eloy Detention Center, or inside a Las Vegas casino, for example. My awareness of various constraints and control is maybe reflected in the lines and in the poems’ shapes on the page.

There were a few poems whose form emerged as one thing and remained that way or defied formal revisions. “At the Window,” “Witness Statement,” “The Inheritance of Intelligence”, and “Letters to Bernadette” are some of them. Of course, those poems were revised many, many times, but they always restored their original form.

The couplet is a frequent formal choice in these poems. I’m really interested in the tension the couplet can generate, particularly in its ability to momentarily fracture some sense of order or understanding and also in its capacity to repair itself, or disambiguate, when we move from line to line or couplet to couplet. It’s a powerful unit and meaning multiplier that can complicate and clarify meaning, sound, imagery, in one deft moment. That energy and power to fracture or disrupt, and subsequently repair, order—all while existing as an order of form—is thrilling to me. Bertillon was known for his obsessive love of order, and though he entered my orbit after these poems were written, it’s interesting to retroactively consider the ways the couplet can be an agent of disorder.

Other poems in the book take a columnar, stichic form and those poems are often more narrative in nature. I love the movement through various ideas and images in a narrative poem, and the layers of resonances those ideas or images generate when placed alongside one another in the same architectural space. Even if there’s not an explicit or intuitive connection between them, their very proximity and associative movement from one to the other establishes a connection between them. I like how those movements can create what Teju Cole calls a “tangled tree of meanings.”

You bring up how “At the Window” seems like it’s stretching toward the other end of the page. When I think of stretching in regard to this poem, my mind goes to yearning. I wrote that poem while sitting next to my dying grandmother at the window she sat by all day, everyday, in the final weeks of her life, waiting for the ruby throated hummingbird to visit the feeder. I felt desperate to preserve those moments I spent sitting next to her. Maybe the stretching lines reflect that desperation. I was acutely aware of how disorienting the opposing forces were in that setting and experience: a collapse of inside and outside, a dissolution of distinction between living and dying, the absurdity of birth in the midst of death. In her final hours of life, I whispered a secret in her ear that I had told no one else—that I was becoming a mother. What container can feel right to hold immeasurable grief and immeasurable joy simultaneously? I’m not sure.

KJ: So compelling how some of the forms keep that container and how other forms are shifting and spreading or minimizing. With that, and with “Letters to Bernadette” ending the collection, I was so taken by the epistolary form and the way that it on page 83, lent itself to the single line. And I was thinking about the creation of the letters, their length and levels of intimacy. How are notions like origin, birth, continuation and motherhood present here, and how is the intimacy of the epistolary form interacting with surveillance?

CR: I think of “Letters to Bernadette” as a sequence that holds the primary themes of the collection, which are a nearly painful desire to bring life into the world amidst all the attendant anxiety of its violence, a contempt for the state and violence it sanctions, and an increasingly agitated vigilance that teeters on paranoia. These letters feel very intimate and social to me simultaneously, which is an orientation that I think the epistolary form is particularly potent for. But I didn’t set out with a conscious intention of the epistle as a form for this sequence. They emerged as letters organically and remained that way. I think of them as a love letter, a diatribe, a warning, a dirge, a plea, a prayer.

Like many of the poems in this book, I wrote “Letters to Bernadette” during the first Trump presidency, which was, among many things, a time of unabashed vitriol and hostility toward migrants. ICE was everywhere. I saw ICE agents apprehend a father in the early morning who was walking with his children to his car to take them to school. I saw ICE vehicles in the valet zone of a hospital in Tucson on Father’s Day where families filtered in carrying Father’s Day balloons. On that same Father’s Day, I was at the wall in Nogales at the spot where, in 2012, U.S. Border Patrol agent Lonnie Swartz fired 16 shots from the U.S. side over to the Mexican side at sixteen-year-old José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, where a mother and her two children stood to talk to their husband/father on the Mexico side. ICE agents would wait outside the courthouse in Albuquerque where undocumented people would

arrive for their court appearances. Six ICE agents showed up to a courthouse in El Paso where an undocumented woman went to seek a protective order against her boyfriend she accused of abusing her. I saw gallons of water slashed by Border Patrol in the Sonoran Desert which humanitarian aid workers had left for migrants. All of this is vile and depraved. This has been and is the reality. To be sure, it’s not a reality particular to Trump. Obama was Deporter-in-Chief, and Biden was just deemed Returner-in-Chief for surpassing Trump’s total deportations during his first term. And of course, Trump came into his second term guns blazing with vows to carry out the biggest mass deportation campaign in American history.

My husband is a Mexican immigrant. Our children are the first children of his family born in the United States. I wrote “Letters to Bernadette” just before I became pregnant with our child. A fear for his life and safety—and that of half of his entire family—is in these letters.

KJ: I found myself traveling for the holidays while I read your collection and your specific poems side by side entitled “American Landscape” came up while I was about to get on an American Airlines flight home and I had this moment where I was thinking about generative moments when in transit. I was curious about the in-between places, the layers of becoming, and also thinking about surveil and its interaction with watching. There is so much even in the name American Airlines, in the first poem, “American Landscape [on an American Airlines flight to Las Vegas, Nevada]”. I was thinking about these specific poems, because they are very deep rooted in setting, but also speaking to something so much larger than just the place itself. I was curious about the construction of these poems, were they scrawled on a notebook? Were they typed on a notes app on a phone? Or a voice memo? Do you ever write in transit? Or do you think about the interactions/observations and write later?

CR: You nailed it on the head! All of those modes—scrawling in notebooks, audio recording, notes app on my phone—are part of my writing process, both in the “American Landscape” poem you mentioned and in the collection as a whole. And you mention transit and place—I feel very impressed upon by and responsive to place, and I’m always documenting or recording in some capacity. Much of the material in the poems is a record of transit. The poems in this book were written mainly in Iowa City, Albuquerque, and Las Vegas, respectively (where I lived during the course of writing this book) and most of them were written during Trump’s first term. Many of the places I’ve lived in or spent time in have been politically charged places: Creech Air Force Base, outside of Las Vegas, Nevada; Friendship Park at the U.S./Mexico border; Ciudad Juárez; White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, to name a few. These places, and their essential natures of violence, mark the poems.

KJ: Were there moments that defined the collection for you? Were there moments of breaking? Were there moments where you felt the weight of surveillance while writing? I just felt, especially as a reader, the speakers themselves and the work of that weight.

CR: I had been submitting some iteration of the manuscript for the better part of a decade before it was picked up, so there were many moments of breaking! There was a lot of frustration and discouragement, and many times I wanted to throw in the towel. The night before I found out the manuscript had won the prize, I had become so discouraged and felt like the time had finally come to call it. The next morning, I got the email. Finally something had broken through.

The earliest poem in the book is from 2013 or 2014, and the latest poem in the book is from 2019. Throughout that chunk of time, my life changed in a number of ways, my reading changed, I changed. So the work changed too. I had experiences and exposure to things in 2019 that were so different from what I experienced in 2013. And so something I felt constantly throughout the process of trying to make this a book was how to reconcile which poems felt like they belonged within the walls of this book, which ones felt like they belonged elsewhere, and which ones didn’t belong anywhere. That’s a very ordinary trouble for a poet, of course.

I welcome the idea that a poem can be made and remade endlessly, that it can end up a radically different animal from how it began. I’m not afraid of going through with a scythe or excising. Often I have to jettison the work from

my orbit for a while and return to it as a different animal myself. But in short: yes, this manuscript gave me a lot of trouble. I struggled through it the whole time.

There were a few poems that felt like anchors to the book: “The Rut,” “The Inheritance of Intelligence” and “Letters to Bernadette.” I wrote “The Rut” and “The Inheritance of Intelligence” within a week of one another in early 2017, right after Trump took office for the first time, and once they materialized I felt like they were framing poems. Similarly, after I wrote “Letters to Bernadette,” I had a strong sense it would be the last poem of the book. Once that framework emerged, the constant thereafter was: how is everything else going to relate to each other within this framework?

KJ: You mentioned the collection not having a sense of direct linearity, I wanted to ask about the numbered form of the different sections of the collection in connection with the use of brackets?

CR: While the poems don’t track linearly, necessarily, they do exhibit a progression. The book opens in the thick of the speaker’s desperate desire to become a mother and ends with the speaker on the cusp of motherhood, nearing the birth of her first child. Among and between those two points of the speaker’s trajectory is a tangle of themes of control, watching, being watched, fear, paranoia, violence, love, and death, among other things. The numerically titled sections gesture toward that progression. It’s not a proper arc, but a furtherance or points on the trajectory. I think of the brackets functioning as a kind of quiet admission of that progression. Throughout the course of writing this book, I was never working toward an explicit project—I was just writing poems and then trying to figure out how those poems were relating to one another. And so the brackets, to me, felt like signals of the differences among how the groupings of poems relate to each other. I think of the brackets as gestures. There’s something that feels more porous to me, less final, about brackets than how I think about parentheses.

KJ: Yeah. And I think right as a reader, the brackets really stood out to me, in terms of interconnectedness. There is progression, but the progression itself is not linear. Even the brackets themselves visually, it’s sort of a box, but it never quite meets, and so there’s space for branching out or for movement.

CR: I love that read that the box never meets and so therefore allows movement into and out of them. I didn’t want to signal a definite closing off of one space and the beginning of another, but instead a continuous movement between all open rooms.

KJ: Thinking of brackets versus parentheses as visual cues throughout the numbered sections, did using parentheses ever enter your mind?

CR: I love that you attune to the textural or gestural differences between parentheses and brackets, because those minutiae are alive in my mind, so thank you for that!

They were always brackets and never parentheses. Parentheses felt like too private of an aside for the poems, or a stepping-away-from, whereas brackets, to me, feel like part of the ongoingness, a brief addition to the continuing sentence, utterance or thought. I may have my gestural impressions inverted here, but this is always how the two have felt differently to me.

KJ: Thinking at a line level or rather syntactic formation, I was really curious about root words, definition and compartmentalization, but also bringing it together in the rhetoric of the poem “Derivations.” How does this sense of zooming in or zeroing in articulate seeing, and what does that mean for the whole?

CR: Migration and movement, specifically what movement is allowed or disallowed, whose and to where, is something that was foremost in my mind as I spent time with this book. In that particular poem, the idea I was turning over had to do with ontogenetic development: that an organism’s whole development is the result of or is determined by its interactions with its environment, rather than its genetics. I was also thinking about the highly curatorial and imperial nature of naming, and names as sites to investigate power.

KJ: We touched on this, but I was curious because you have because there is such attention and specificity to the different individuals that you did include past presidents, drone operators etc. So I was curious about including the many, being a part of a larger conversation, and what that means to this collection?

CR: There’s a lot of language in the book that is not my own. I wanted to be in active dialogue with those other voices. Often those voices are spoken through the mouth of the state, and I wanted to respond to them rather than passively receive them. I don’t mean to claim that responding

in this manner makes anything happen, but I was curious to explore how rendering language of the state in a conversational context might illuminate the insidiousness of power and violence wielded in our everyday lives that we often passively or subconsciously accept. That was something I was thinking about in “The Inheritance of Intelligence” for example. When I read that poem aloud, the listener can’t distinguish between my own language and the language of the state. That slippage is demonstrative of the insidiousness, I think. The justification of violence and obliteration is often deployed through quite quotidian language. “Before any strike is taken, there must be near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured—the highest standard we can set,” Obama remarked at the National Defense University in May of 2013. Near-certainty. Or point and click. Or the officer feared for his life. That’s all it takes.