Interview // “Moments without Anchors & Intimacies without Control”: A Conversation with Taneum Bambrick

by Sarah Bitter | Contributing Writer

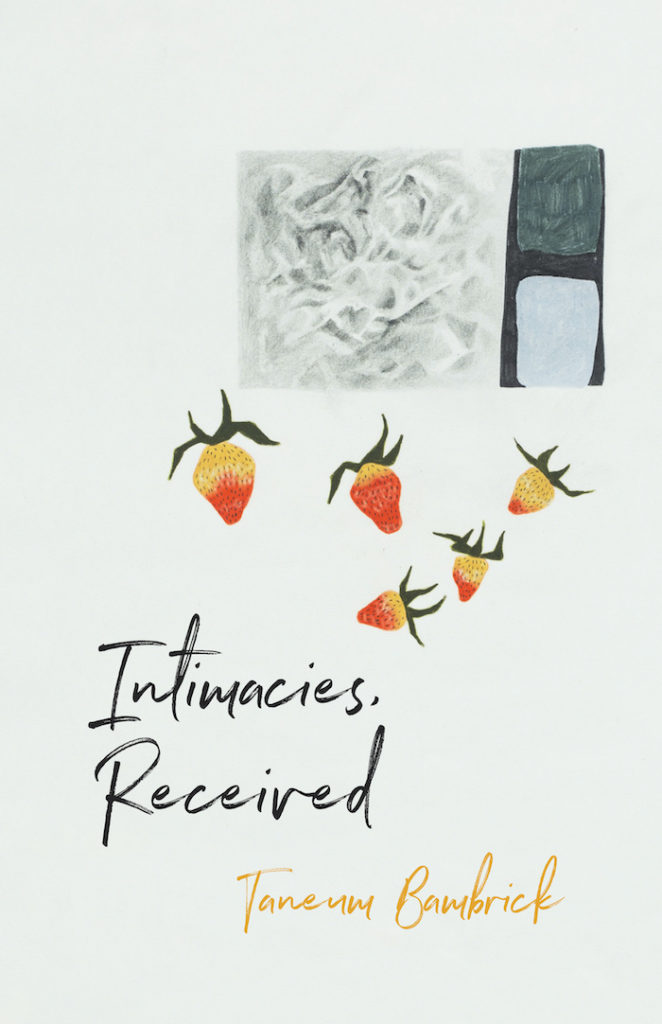

Taneum Bambrick, author of the new collection, Intimacies, Received (Copper Canyon Press), conversed with me via email about her new book (although our conversation also touches on her first collection, Vantage, winner of the 2019 APR Honickman First Book Prize, also from Copper Canyon).

*

Sarah Bitter: Taneum, thanks so much for this dialogue about Intimacies, Received. It’s quite a development from Vantage, which I also loved. So, let’s start with how and where you wrote it. I believe you were on a Stegner Fellowship and your professors were (OMG) Louise Glück, Eavan Boland, and Patrick Phillips. Can you talk about how working with them impacted this book and your writing?

Taneum Bambrick: I love this question! I don’t think I’ve ever written about my time at the Stegner. I could not have written this book without those two years I had to write and work with some of my favorite poets.

Eavan Boland was fierce and difficult to impress, which made me write towards her obsessively, almost like a prompt. She had things she’d often say about poems she loved, like “this poem has an emotional color.” She passed away while my cohort was there, and that was incredibly difficult for all of us. I think of her often, still. She made me more precise, and I wonder if I will always hear her voice when I revise.

Louise Glück is one of the most generous teachers I have ever worked with. She held workshop in her home and gave us difficult prompts, which broke me out of my habit of only bringing in poems I’d been editing for months into class. There is something magic about working with Louise, and it’s not just her generosity. She helped me see where I was stuck. Working with her made me more curious and more honest with myself.

Patrick Phillips is incredibly kind, energetic, and supportive. He has remained one of my strongest advocates even years after we worked together. He read and wrote notes on every single poem in Intimacies, Received. Of all my professors I think he is the one who helped me most with editing this book.

My cohort at Stanford—particularly my year—Colby Cotton, Jay Deshpande, sam sax, and Monica Sok—were also my instructors. I feel so much gratitude when I think of them and the cohorts the year above and below ours.

Today, thinking about the Stegner, I am remembering Courtney Kampa who passed away suddenly just over a month ago. I still don’t know how to talk about this, but I feel like I need to keep trying. In workshop, she often said a strong poem was “gutting,” and I’ve noticed people using that word to describe how they feel after losing her. I feel gutted, too. I also feel so lucky to have known her, to have received many pictures of her sweet little dog over the years with a permanent, red kiss-mark between his eyes. She was so protective and caring towards every person and animal in her life.

SB: Time well spent; Intimacies, Received is precise and curious and honest. Also, I’m so sorry for your losses. Two great writers, Boland and Kampa. I just read a few poems by Courtney Kampa—beautiful. Thanks for mentioning her to us.

Considering how Glück influenced this manuscript, I’ve heard you say that the “Untitled” poems which introduce, end, and section the book, were the product of an “intimacy diary” you were encouraged to keep by her. Can you tell us about that?

TB: Yes, I think I called it that on my own—I am not sure if she had a name for it. This exercise was one of those habit breaking ones I mentioned earlier. She asked us to write, essentially, notes every day for seven days. Those notes had to be short and centered on image, observations, thoughts, dialogue, etc.

Before I met Louise, I hated prompts. This prompt changed my life. Through it, I learned to lose control and to focus on accumulation and chance. Writing a little every day felt like a kindness, or a game of tag with my future self. When I sat down to write, I’d already written something, so I felt an immense pressure release. This was important for me because my book looks at a lot of difficult subject matter, like sexual assault, queer erasure, and chronic illness related to sex. I needed, and I think the reader likely needs, some blank space, some time and levity.

SB: I can see how the untitled poems allow both the speaker and the reader space, which you’re right, is space we probably need to consider difficult material—sexual violence and other violences inherent in patriarchy and capitalism. Can we talk about violence(s) in this book? Perhaps you could use the first poem in the book, “Untitled 1” as a window into how you explore this?

TB: When I worked with my editor Michael Wiegers on this book, he said, “this speaker is a romantic,” and that shocked me. He moved that untitled poem to the front of the book because he felt it demonstrated both the idea of a speaker whose understanding of her intimate self had been compromised by trauma, but also the idea that this speaker actively refuses to let that narrative of sexual trauma surround and confine her. Together, we worked to unbury the notions of resilience, curiosity, and tenderness from the book.

SB: Wieger’s observation also shocks me, but he’s right. Your speaker is tender, strong, and questioning. I’m so glad you mentioned resilience in the face of violence/trauma, because, as you say, your book is at least as much about resilience and curiosity as it is about violence.

Speaking of curiosity, I am so curious about how people are and are not named in your work. In your first book, Vantage, the men you worked with and people around them are often referred to by first names, as are others. In Intimacies, Received there are fewer first names: the speaker’s intimate female partners are identified by only an initial, and the speaker’s primary intimate male partner is not named at all. For me, this naming and not naming accumulates meaning.

TB: Writing Vantage, I borrowed form from fiction and nonfiction in terms of story building, character, and dialogue. I wanted to write the story of my time working on a garbage crew almost cinematically, because those memories were bright and sharp in my mind.

Intimacies, Received charts a time that I can barely hold; I don’t trust these memories in a literal way. I am writing into the year I spent almost half my days in bed, sick with a fever and a kidney infection that kept coming back. I changed because of pain. I valued myself and the conditions around me less. With this collection, I wanted to write into the internal, particularly the fluid natures of gender and sexuality as I’ve experienced them. I also wanted to write into the shame I’ve grappled with after experiencing UTIs and yeast infections because of sex. For example, what does it mean when our bodies resist a partner our brain refuses to recognize as toxic? The literal details felt less important to me because I was trying to capture this idea of isolation within a wrong or fraught intimate context.

SB: I do feel a kind of empathetic isolation as I inhabit the world of your book. That said, there are literal details I loved for their tenderness: children playing as alligators, a little dog that opens a door with its mouth—as well as some details so devastating I don’t want to type them (the other dog).

Speaking of details, you frequently place images/things/events/ideas next to each other, leaving it for readers to make out a relationship. (As you observed in Vantage, “placing different issues beside each other / in a sentence // What is given similar weight conflates” (47).) Could you talk about juxtaposition in your writing?

TB: I’ve learned a lot from my wonderful friend Claire Hong, particularly her book UPEND. She and I did our MFA together at the University of Arizona and then we overlapped at the Stegner one year. In her collection she writes “someone can replace someone with a like or as.” Because we both wrote our first books in the same program, I see that we were thinking about the potential consequences of metaphor, simile, and juxtaposition at that time. I am careful with comparisons, but also, in poetry, we are taught to compare. This trap is interesting, and I can’t think of a book that handles it better than UPEND.

In both of my collections, I’ve tried to write a scene as closely as I can without looking away or dragging something else in to contextualize it. I am interested in how a poem can point itself at a moment without giving that moment background to anchor it. For this reason, it’s often hard for me to place individual poems from one of my book projects in magazines or journals. Together, they make sense, but in isolation they can be confusing. In my first two collections, I wanted to build worlds where the poems needed each other to make sense, and I think that goes back to this idea you’re pointing to about asking the reader to “make out a relationship” rather than being told or shown what it is.

SB: The way that you write without looking away and resist contextualizing is a distinguishing feature of your work. Sometimes, I want to cover my eyes with my hands when I read your poems, (I’m a complete coward in the cinema) but I must keep looking; unlike a movie, the poem won’t go on without my effort. Your reader also must enact that unflinching gaze.

Along the topic of relationships: Intimacies, Received considers the family unit in many poems, and more specifically, the patriarchal family of the speaker’s male, Spanish partner. I’m interested in your attention to this male-dominated family (and society) next to the ideas of queerness in the book. For example, in “Untitled 7” the speaker quotes: “All independent lesbian films end / with the lead going back to men.” And then the speaker observes: “More than love, I choose disappointment” (35). Can you talk about how your work explores tension between queerness and the “traditional” family? And how you write into expectations of women within “traditional” family and gender expectations.

TB: In Intimacies, Received, the speaker has moved to a small town in southern Spain where she meets only one other queer person. She enters a relationship with a man who asks her to keep her sexuality a secret from his friends and family. While this experience might seem magnified due to location, it’s not so different from what she lived growing up in rural eastern Washington State. This speaker is very close to me and who I was at this time when I was starting to question my gender identity, as well as my sexuality. Being in a straight presenting relationship while carrying these questions around was difficult, especially because sleeping with this person was making me so sick. Every day felt pressurized. I was unable to identify what was safe and what was a risk.

It’s hard, when you love someone and their family, to keep facets of yourself secret. I have had multiple partners not mention my queerness to their friends and family. In some of those instances I didn’t put in the effort to make myself known, which created a wedge of resentment I didn’t realize I felt. I wanted Intimacies, Received to write into that confusion of instances where I felt almost selfish for wanting to come out.

Also, that quote you mentioned “all independent lesbian films end / with the lead going back to men” is something a man literally said to me once, and I had it in my phone notes for YEARS before finding a way to put it in a poem.

SB: I’m going to be thinking about this answer for a while because it illuminates many threads in the book: suppression of identity, how stress clouds judgment, and the cost of making oneself known, which is so much higher when one is “othered.” Thinking about that cost is a good segue into my last question:

You write insightfully about being seen: about how women and queer identities are and aren’t seen, and about how women control and don’t control how we are seen. For example, in “Dating” (25) you write of your partner’s mother: “I would like to be what she knows of women. / Smiling, they expect a scream.” I’m also thinking of the moment when the speaker is observed, naked while she sleeps, in “The Meat Carver” (19). Again, this is a theme that carries from Vantage where you write: “they only see you in relation to them being the man,” (12). Come to think of it, your two Picasso poems in the new collection also investigate how women are seen and made to be seen, as well as how the female speaker sees. Can we talk about seeing and being seen in your work? Are there theorists or other writers that influence how you approach this topic?

TB: I found new poetry and friendships after publishing the poem “Bisexual Erasure” in BOAAT when that publication was still running. My dms were full of poets sending me their poems on this same subject. Publishing it revealed to me that this was an area a lot of people are interested in. I no longer identify as bi, and the poem is called “Erasure” now. It ends “I am queer in a way that might puncture the conversation,” so several readers had questions about the speaker referring to themselves as queer and bi in the same piece. That slipping is natural for me, but I understand why it could be confusing. Regardless, that’s not why I changed the name. The poem is about what, at the time, was bi erasure, but it is also circling around other ideas of erasure: the erasure of pleasure, the erasure of self-love and self-eroticism. The speaker is sitting in a restaurant with a group of women who identify as straight and hate the smell of the oysters the speaker is eating, which they compare to the smell of their own bodies. They feel revolted imagining what their husbands taste while going down on them. They say this in front of the queer speaker who they assume is not queer, and this assumption makes her feel both invited in and pushed out.

I hope this and other poems, especially couched between poems about body shame stemming from chronic illness, work to build an understanding in the collection about how that learned shame is not only toxic, but threatening. In Intimacies, Received, I’ve tried to write the story of a speaker who kept her pain a secret because it embarrassed her. Waiting to seek medical care for a UTI sent her into a spiral where her kidney infection was so severe, a doctor warned that having sex could kill her if she didn’t wait to be intimate until she was entirely better. In the poem “Ecjia,” I chart the moment when her partner, having heard this warning, still initiates sex with her, and the speaker, feeling desired, says yes. I wanted to demonstrate how impossible it can feel to withhold sex from a partner when their attraction to you seems like all you’re bringing to the relationship. I hope this won’t read as me airing the dirty laundry of one relationship, because when I wrote this I was thinking of patterns, and the extremes we reach until a pattern is finally disrupted.

—

Taneum Bambrick is the author of Intimacies, Received (Copper Canyon Press), and Vantage (American Poetry Review).

Sarah Bitter is a writer from Seattle, Washington. Her work can be found in Denver Quarterly’s FIVES, Seventh Wave, River Mouth Review, and other publications.