Interview // “Mechanics of the Haunt”: A Conversation with Clara Burghelea

by Shriram Sivaramakrishnan | Contributing Writer

Shriram Sivaramakrishnan: I would like to kickstart our conversation with the interview you gave to Newfound in 2017. You touch upon a couple of things that I think are pertinent to your poetics: your upbringing in Romania, being identified as a Romanian-born poet with an MFA in Poetry from Adelphi University. Do you see yourself this way, when you write? How accessible were these identities to the speaker of Praise the Unburied?

Clara Burghelea: I am not actually aware of this identity when I write but, though my poetry is written in English, it is strongly infused with my Romanian emotions. The poems in The Flavor of The Other, my previous poetry collection, were written while I was commuting between NY and my hometown in Romania, in the in-between spaces/states of mind. Praise the Unburied, as I wrote in the description, takes an interest in the edges where the languages, English and Romanian, form and subjectivities, meet. It explores my haunts, absences, preoccupation for the body, motherhood, the constant state of suspension where I feel I dwell; and these define me, to a great extent.

SS: I love the phrase “constant state of suspension.” To be somewhere and nowhere at the same time. In a way, it is akin to being “in the middle of things,” the way the speaker’s mother is in the eponymous poem “Portrait of my mother in the middle of things.” One of the things that drew me to this piece is the thought: “Forgetting is essential.” I would like to believe that the act—or the reality—of forgetting is important for those of us who want to dwell in the middle. I suppose what I am trying to ask is how immersed in “haunts, absences, preoccupations of the body, motherhood” were you when you wrote the poems? I have another reason to pose this question. Consider the way the aforementioned thought ends:

Forgetting is essential,

she said as she dunked her fingers into hot water

only to come out perfectly polished, no smudge

whatsoever.

I am tempted to read this as an allegory for writing, for remembering and recollecting in words.

CB: I believe I have been deeply immersed in the mechanics of my haunts as I was writing the poems. They are hard to miss, unavoidable.

At times, forgetting is essential. In the poem, that refers to the way one person, a mother, a woman, part of a traditional family where roles and expectations are clearly cut, needs to forget about that part of hers in order to breathe, to tend to the little things that make her happy—like doing her nails—to keep it going. We are a multitude of things, after all.

I guess it applies to poetry writing in terms of revision. I find revision to be a never ending process. A poem might shape and shift several times before reaching its final form. Which might seem to be the final form at that very moment and once I see it in print, for instance, I might find myself questioning its form or playing with words. So it makes sense to forget about all these and move forward.

SS: I see what you mean. I would like to think of “mechanics of the haunt” as a kind of trauma response, but then the speaker is immersed in the mechanics of it, rather than the thing in itself. I am interested in what you think are the mechanics here, and if you would consider language as one? I ask this because of one of the sections in the book, Ghostification and the eponymous poem. I googled the word. Apparently, it can refer to the presence of the absence or the absence of the presence, like desertification (which can refer to both an erosion of fertile land, but also the creation of a wasteland). Do you see it this way too? You touch upon it at various places in the section. In “Limenas, half-light,” the speaker ends by saying: “By dark, I’ll become a ghost, / all foam and salty limbs.” In “What occasionally makes sense” (and I love the title!), the speaker says: “there are no rooms in our bodies without ghosts.” There is something elusive about the ghost in these poems. I suppose my question is how responsive were these ghosts to your language?

CB: I like the way you framed it: the presence of the absence or the absence of the presence. That is exactly how I see it. I think absence, the lack of someone/something, also speaks to how fallow a poet might get in between the highly creative spurs of the moment. As for the ghosts and their responsiveness to my language, there were moments when their elusive presence or abundance came to inhabit the page unawares, or when the same presence vigorously scratched every moment of the day. “Things exist long after they are killed,” says Joshua Jennifer Espinoza in “Things Haunt.”

There is another poem that skillfully captures both fatherly presence and non-presence: Haunt by Maya Phillips:

And maybe the young man knows nothing

of the dead man, has no words

for a ghost who builds a home

of his absence. And if my father says haunt

he doesn’t mean the way rooms forget him once he’s gone

I very much like the idea that a poem could be a home of someone’s absence. It could also harbor the absence of a thing, a feeling, a place; though, within its space, that very absence acquires a voice and flesh.

SS: I love that poem by Maya Phillips! It is a poem that I go (back) to, time and again. I do think that “a poem could be a home of someone’s absence.” And speaking of home, one of the tropes in this collection is windows. In Ghostification, the mother figure is “by the window, watering the plants.” In “I haven’t thought about my mother in months,” the “window’s reflection” allows the speaker to, for want of a better word, superimpose her act of reflecting (thinking) about the mother figure. In “Three winks,” the “window frames / a square of green-smeared light,” while “trees thick with vibrant green” press against the open window in “Of forgotten tastes.” And while the window can be a poetic device, in allowing a poet to think, à la Keats, I am more interested in the way you have used it to juxtapose various figures and events from your memory. What I mean is a sense of interiority, a notion of the home as a space for dwelling. I am, in a way, cataloging your prepositions. Going back to Ghostification, as the mother figure is immersed in the task of watering the plants, the speaker spots “behind the curtains / a tissue of cloud.” In “Contra temps,” there is an outsideness: “Outside the window, / the postcard home day peels off in slow motion.” A similar thing happens in “The twenty-year marriage.” On the contrary, In “Three winks” toys with an insideness: “Inside, a poem / holding its breath.” The son in “Called by others to grow upwards” gazes “outside the window.” Windows can act as transitional zones between insides and outsides, but also between here and there. Is there something more to the window motif in your writing, given that windows are an integral part of what makes a house a livable home?

CB: Thank you for the specific question and the close reading.

The window is one of the recurring symbols of the collection. It is an entry point in all the houses in the collection. It is an eye into each poem’s house or a portal into a memory. The same motif is present in my previous collection because I am drawn to the way windows can give one light and protection in the sense of allowing one to look outside from the comfort and safety of an indoor space—that tensioned relationship you mention, the outsideness versus the insideness. In ”Three Winks,” for instance, the window acts as a reflection of the light, a mirror for the poem, dwelling inside, holding its breath. Windows also give the looker a sense of intimacy, as well as the awareness of shared complicity. As a poem architect, the poet has permission to slide in between spaces, to inhabit both places and build the poem, form and content wise. This always has me thinking about the reader and how by immersing into the poem, close reading it, they can add an extra lens or use their own window into the poem.

SS: I am reminded of Emily Dickinson’s “I dwell in Possibility,” a poem as much about windows and dwelling as it is about poetry and possibility, in which she says: “More numerous of Windows – / Superior – for Doors –.” It seems, in this poem, as well as yours, memory-as-space remains enclosed rather than elongated, by which I mean, memories function more like houses than like amphitheaters. There is a definite sense of confinement. In “Needle threading towards reparation,” the speaker starts the act of recollection by stating where she is spatially situated: “I am looking at us from the inside” and goes on to acknowledge that “trusting the hours / that pass to help me shake off any fleck / of memory.” The poem concludes with “neither to be eaten, nor thrown away.” In “What occasionally makes sense,” the speaker says: “making things up as they come along.” I can’t help but think of it as an allegory to writing. All of this makes me wonder if the speaker is trying to access the memory or release it, as she tries to shake it off? More importantly, how did poetry help you shake off those memories?

CB: I often ponder the accuracy of memories. Our sense of the past is constantly shifting, so how much is it our own construction of the self through poems and how much is it part of the process of remembering? My poems engage with this exercise in recalling, reshaping, and revisiting memories. It felt more like access/release when I was writing the first collection since I was in a sort of self-exile, abroad, separated from family and everything familiar. Praise the Unburied is more about navigating the space between fact and fabrication, while saying something essential about identity. To answer the last part of your question, I did feel using poetry to shake off memories, and construct new narratives of the self in Praise the Unburied.

SS: I love the idea of using poetry to “construct new narratives of the self.” At the face of it, this whole journey, of “navigating the space between face and fabrication,” with nothing but the rhythm of words seems very Orphelian. I say this because the collection is full of tropes—whether in the form of idiomatic phrases or symbols—for traversing this cavernous space. I think of them as belays. We already touched upon windows. I want to turn our attention towards another: colors. There are too many instances to quote but I will try. The “slaty-blue eye of the jay” and the “torturing green of the grass” in “Anatomy of a single sun’s day”; the “teal-smeared wall” in “Contre temps”; the lavender sky in “At the villa”; the brown apples in “A day spent curled around your face”; my favorite, the black coffee in “Under eyelids”; and so on. Colors seem to embellish your poems, but also, at times, ground the language onto a memory or the memory within a narrative. But how do you see their role in “saying something about identity”?

CB: Food was the red thread in my previous collection, tying one poem to the next. It was never intentional, yet while curating the collection and perusing language, as I am always very conscious of writing in an acquired language, not in my native one, I found a food reference in every poem. So this became a sort of funny, little detail until one reader picked up on it.

All the colors are present in the poems of Praise the Unburied; some mentioned only once, others used ten times. They always work beyond their chromatic attribute, grounding language to a memory or the memory within the narrative. They may set the tone or mood, or shape the reading of the poem. Starting with Rimbaud’s sonnet, ”Vowels” that spoke of the synesthetic experience, to Dorothea Lasky’s essay, “What is color in poetry,” we have learned that colors are more than a decorative element in poetry. They implicitly reveal something of the poet’s identity, such as the Romanian cultural heritage, in my case. For instance, there are 230 colors used in the line-up of the Romanian folk costume.

SS: That is fascinating. The other thing that I wanted to talk about is the sudden shifting of registers. The poems go from the personal to the political in a span of a few pages. I am referring to the section, How to turn poetry prompt #5 into girl power. Even within this, the tonal shift from a poem such as “Ambience of elsewhere” to “What makes a girl” seems a little too abrupt. The juxtaposition there took me by surprise. The same can be said about most of the poems in this section before the tone falls back on the personal in the next section, Self-medicating with St John’s Wort. Given the persistent role of memory and cultural nuances in the first two sections, Ghostification and A Tincture for Wounds, how did you arrive at this shift, by which I mean, how did you arrive at the structure for the collection?

CB: Indeed, the personal shifts into the political and then falls back onto the personal.

In curating this collection, I deliberately decided upon having sections that would easily guide the reader into the folds of the book. This speaks of my preoccupations at the time—compartmentalizing to better grasp all layers—as well as my interest in how the female body is seen as a commodity and often preyed upon.

Having children of my own feels at times the supreme vulnerability. Some poems reflect my fears and questions about how to teach them that the handling of a body is part of the growing up process and that the body is wide and generous enough to accommodate all that is ”us.”

For instance, How to turn poetry prompt #5 into girl power is about the compromises that language under patriarchy offers. It is a form poem, where every one of the fifteen lines is made up of fifteen syllables. The tension of the form is illustrative of the pressure put on the female identity in every traditional, patriarchal society. It is dedicated to my fifteen-year-old daughter. It is a poem that speaks of how the social, the personal, and the political overlap, and how this fluidity is, to a certain extent, mirrored in the shape of the collection.

SS: I love the word “curate.” Given the politics the collection alludes to and deals with, this word assumes significance in terms of implications. As a curated work, I think of Praise the Unburied as a collection that acknowledges the past yet remains rooted in the present but with one eye to the future. When the speaker says: “Give yourself room to err” in “Prayer with lullaby eyes,” I find myself seconding it. My favorite piece of the entire collection is “A poem about things I became good at losing.” It provides space for catharsis, one that we need, especially in times like this. So where do you go from here as a poet? Are there any pet projects on the horizon?

CB: Every collection brought me closer to the whole process of curating. I also like the very definition of this verb: to pull together, to sift through.

As a poet, much as my work is produced solitarily, I cannot appreciate enough the importance of literary people and the large writing community. I strongly believe in the need to reach out, share, grow together. I am lucky enough to have a few close first readers and I have been fortunate to have unknown people in this literary world that generously lent a hand.

I would love to share my newly acquired knowledge in putting together two collections with others, to mentor and to support. I hope my next project is a beautifully collective project, an art installation, etc or an entire collection with poets who contribute their unique voices to a common project.

I will continue writing poetry and setting up new challenges for myself, form wise. I am working on translating a second book of poetry by Ștefan Manasia, a famous Romanian poet, while looking for a home for the first. I work as a poetry editor for several magazines, so this is another manner of connecting and staying attuned to the rich literary voices out there.

SS: “Pull together,” we must. How much gravity has this phrase amassed in the 18 months or so! And to think of it as a curatorial/artistic practice is, to put simply, the best thing that could happen to a person, more so for a poet. I can’t think of a better way to end this amazing conversation, Clara. Thank you so much for taking the time to answer my questions.

CB: Thank you for taking the time and giving me the space to talk at length about the collection, the process, and poetry, in general.

—

Shriram Sivaramakrishnan is an alumnus of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry and a third-year M.F.A. student at Boise State University. His poems have appeared in DIAGRAM. His debut pamphlet, Let the Light In, was published by Ghost City Press in June 2018. He tweets at @shriiram.

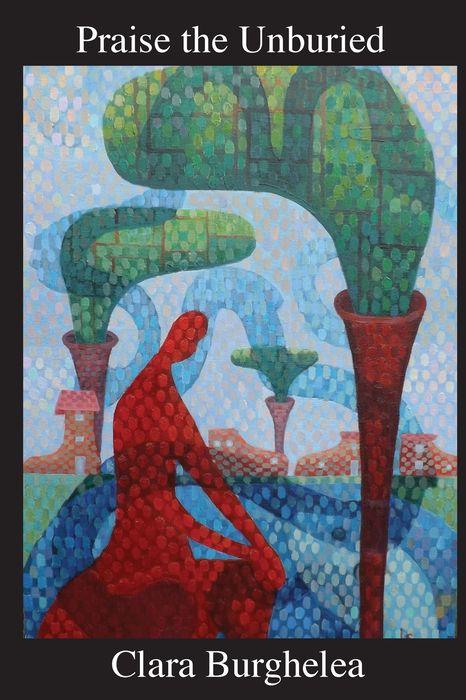

Clara Burghelea is a Romanian-born poet with an MFA in Poetry from Adelphi University. Recipient of the Robert Muroff Poetry Award, her poems and translations appeared in Ambit, Waxwing, The Cortland Review, and elsewhere. Her second poetry collection Praise the Unburied was published with Chaffinch Press in 2021.