Interview // “Making Room for Mystery”: A Conversation with Jessica Jacobs

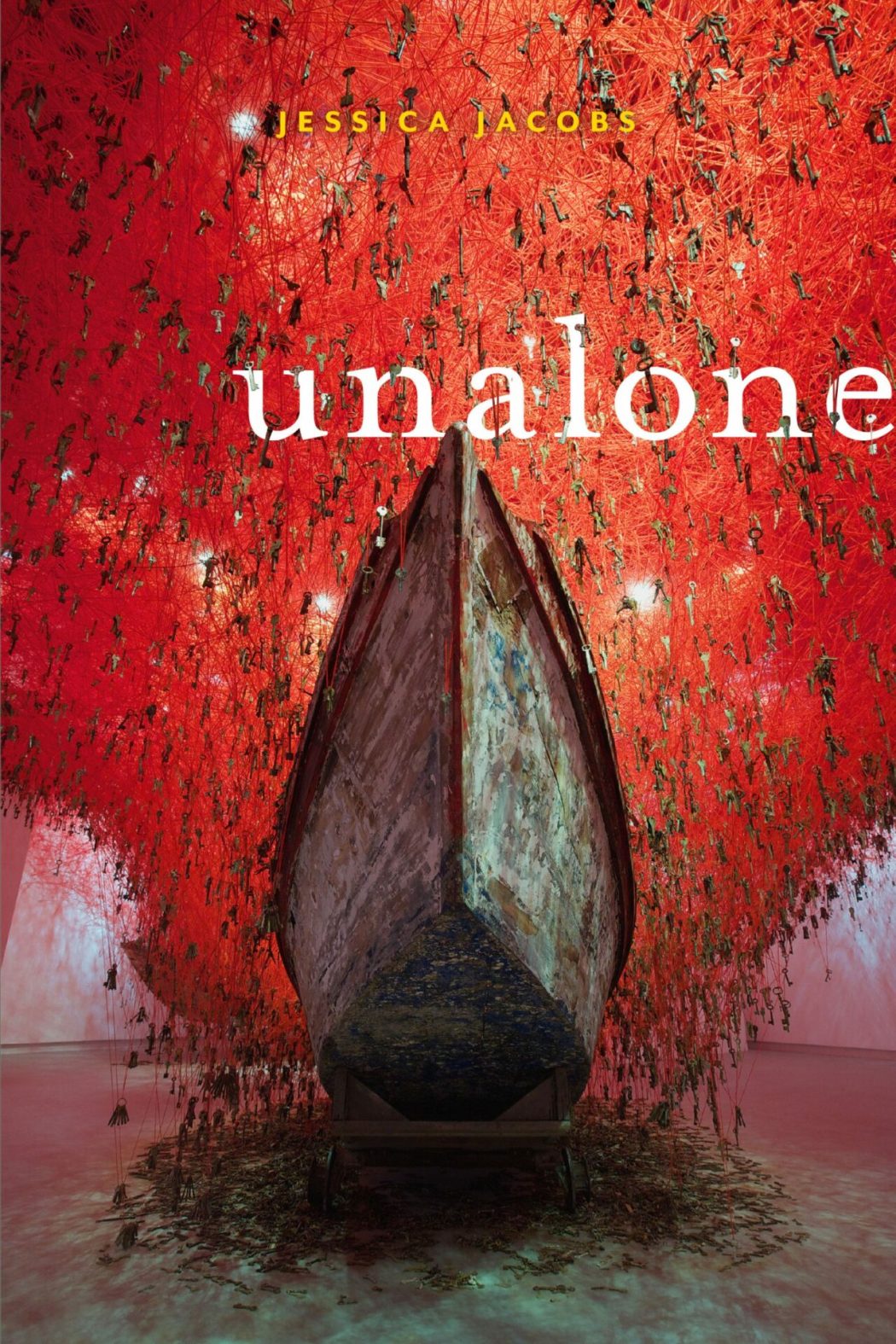

Jessica Jacobs’s third full-length poetry collection is a masterwork in conversation with the Book of Genesis. These poems pulse between the past and present as Jacobs braids the personae of Genesis with the modern themes of migration, climate change, and social justice. More than mere retelling, Jacobs’s uses a blend of lyricism and scriptural language to write herself into these ancient stories. The result is a robust collection of poems composed from “The stories [Jacobs] had to sit with, and ask questions of – until they became [her] teachers.”

I had the pleasure of talking to Jessica after the launch of unalone where we discussed the power of language, story-telling, musicality, and much more in her work.

Anastasios Mihalopoulos (AM): Let’s start with the shape of unalone. The subtitle of your collection, “Poems in Conversation with the Book of Genesis” was particularly striking to me. How do you see the book functioning in conversation with Genesis, as an expansion rather than a retelling or rewriting of it? How did that structure relate to the Book of Genesis?

Jessica Jacobs (JJ): I found my way to conversation as an alternative to instruction or lecture, which is so often how these stories are first shared with us in childhood, often in a very reductive way of which we are expected to be passive, unquestioning recipients of the text. This passing familiarity means we think we know them, like, Oh, I’ve heard that story before, which keeps you from engaging with it in any real way. In contrast, a conversation is relational. Having grown up in a secular Jewish household and having only come to the Torah in my thirties, I felt very much like an outsider, and wanted to engage with these texts the way I would engage with someone who fascinates me. I wanted to try and find ways to say, Here’s how you’re helping me think about my life. Here’s how you’re challenging me. And, just like when you’re truly engaged with someone, if they upset you, you don’t just walk away. I also wanted to write poems to say, Here’s where I find your teachings disturbing and even wrong, where I’m going to push back. The structure of unalone responds to Genesis portion by weekly portion, and many of these poems grew from what I found most upsetting—the stories I had to sit with, and ask questions of—until they became my teachers.

AM: There’s something interesting about the space of persona poems where it’s not retelling, it’s not rewriting, but it’s expansion. In a recent essay, Jennifer Franklin, talked about the motivation for writing through known personae stating “that our collective consciousness already knows the ‘plot’ and the poet can focus on the aspects that are most relevant to the poet’s individual messages.”

When writing into a persona, we understand a story as a part of us, and something we have to engage with. Could you walk us through what it was like writing into some of these personae? I know you use the voices of Abraham, Jacob, and Sarah. How do you view that space functioning?

JJ: The process—so, oddly, for a Jew—I’ve grown a bit obsessed with Saint Ignatius, and actually learned about his teachings at the same time that I learned about Midrash, both from interviews with Krista Tippet for On Being. First, I heard an interview with Avivah Zornberg, a contemporary scholar of Midrash, which pretty much blew my mind, and taught me what might be possible when engaging with Torah, and then an interview with Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest. He talked about the idea of Ignatian contemplation, or imaginative prayer, which is also known as composition of place. The idea is that you don’t need to go to church to pray. You don’t need a priest to reach God. All you need is your imagination and to sit with a story from a sacred text long enough that you can build it like a stage set in your mind, a stage set you can then explore. This is followed by a process of discernment in which you see what you noticed when you were there, inhabiting the story.

I was very moved by this practice, as it seemed to describe something I did instinctually when writing my first book, Pelvis with Distance, which is almost entirely written in the voice of the artist Georgia O’Keeffe. So after hearing Father Martin and then reading his book The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life, I made it a more formal part of my practice and began teaching this method in my classes on both writing contemporary Midrash and writing from general research.

When writing unalone, I would immerse myself in the text—in the Hebrew, in translations, and also in related Midrash and scholarship. From this study, I would gather around me the details that felt most alive, then explore the story’s holes, its lacunae, and find details that felt authentic within the context, but were not actually on the page. This gave me an embodied sense of what these people were doing and maybe a little bit of why, as well as real empathy for them and their often fraught choices. And that’s where the poems came from.

AM: When you were talking about persona and finding this space, it made me think of the tzimtzum that you described in the note section as: “the contraction of God’s infinite self in order to create space, a void, at God’s center in which our world and the free will of those within that world could exist.” And the poem, “In the Beginnings,” takes the shape of that contraction. The structure uses white space to create an opening. I envisioned it as a structure for the whole book in a way. This beam that either opens or allows us in or that serves as a portal into the text. Had you thought about the book as a tzimtzum in this way?

JJ: I’m so grateful to think about unalone in this way—thank you; what a gift. The concept of tzimtzum was put forward by Rabbi Isaac Luria, the father of contemporary Kabbalah, as a way to answer the question that if God is everywhere, how can there be space for the world? Luria’s idea is that God’s self-contraction made space in which the world, including us, could be created. But just existing was not enough; there had to be an animating force that ensouls us and sets us in motion. So Luria posited a ray of divine light entering that open space, infusing every person, animal, and object. Now, many rabbis talk about this concept as a model of how to be in relation to other people, of how we might contract ourselves to make room for other people and to take them in, as well as to how we might then infuse these interactions in a positive way with our will, with our own good intentions.

As I did my research, taking in your beautiful idea, I see how I tried to absent myself as much as I could from the process of creation, to let go of control, to make room for mystery and let the poems arrive in whatever forms most served their content. While I did try to take in as much information as I possibly could, to immerse myself in the materials, I also tried to stay alive to what was called forth in me by the materials, whether it was larger cultural concerns, like the climate crisis, racism, and antisemitism, or more personal memories of my parents, or my relationships. And then I’d infuse what I’d learned from my study with these memories and concerns. It really did feel like a sacred process, through deep study, of building a space within myself, a vessel, in which poetry could then arise.

AM: I think there is a dauntingness to writing into large biblical texts, right?

JJ: Honestly, it was terrifying. That’s part of why the book is dedicated to Rabbi Burt Visotzky. Through happenstance or fate, we met right before the pandemic began because I was thinking about pursuing a Master’s in Jewish studies. In Jewish tradition, there’s a tradition of paired study called Chavruta, which means “partner” and comes from the Hebrew word for “friend,” and Burt said, You already have a master’s degree, why don’t you just study with me? So we’ve been studying together since 2019—me, as this outsider, reading the text for the first time, and Burt as a literal master of midrash, who’s written a shelfful of books in this field. To have someone who’s so immersed and enmeshed in the text say, Oh, that’s interesting. I never thought of that before, was such a gift, such a beautiful model of how to be as a person, and also very validating in that I was finding something with my poems that might be meaningful for more than just myself.

I’ll also say that one of the daunting parts of this process was trying to write poems that would be of interest to someone like Burt while still being accessible to a general reader of poetry who had very little biblical literacy, which meant that I tried to offer enough context within each poem to keep such a reader from getting lost, as well as extensive endnotes—quite the balancing act!

AM: There are so many poems that draw on translations, notably in, “Why There is No Hebrew Word for Obey” where you write,

What if we turn

from certainty and arm ourselvesinstead with questions?

Obey, obey, obey is everywherein translation. The real word is

shema שְׁמַע: listen.

There are so many moments where translation enters your poems in a very fluid and evocative way. How do you see the role of language as a form of power or maybe even revisioning within the collection?

JJ: One of the things I love about etymology is how it reveals how language carries history inside of it. You can learn so much about culture and how culture changes just by looking at how that language changes and what it draws on. With Biblical Hebrew, because it was not a spoken language for so long, a lot of the etymologies are folk etymologies, often uncertain and sometimes very poetic. They offer beautiful mysteries. There’s an amazing book about this by the poet and translator Aviya Kushner called The Grammar of God. She talks about the fact that one of the most incredible things about Hebrew is how every word holds all of these potential meanings within it. And the problem with translation is it only shows the translation the translator chose as the winner, but doesn’t show all the potential finalists, with their multiplicity of meanings and delightful rabbit holes.

As a poet, I love that I can lean into people’s expectations of language and then say, But wait, here’s another way of seeing it. Like in the poem you mention, I can say, Obey is everywhere, right? But actually, here’s what the word literally means. It means listen. And how different is that? How does that actually transform the way that we understand things? So that’s a huge part of it. Translation is such a beautiful act of service. I’m not very good at learning new languages, but I feel like as a poet and a researcher, at least I can become a conduit of the text and hopefully offer what I find between the lines and within the etymology in a way that can be meaningful to people, even if they haven’t sat and done these years of study.

AM: There are so many poems that I love for different reasons in your collection, but one that I was thinking about when you were talking about letting yourself write the poems as they came out in the book, was “Learning to Run Barefoot in a Dry Riverbed at Dawn.” I love this poem. It’s steeped in physical imagery. And I love this idea of an extended metaphor where the imagery shimmers between a capture of physical ecstasy and then the metaphor of learning to read and re-read the Book of Genesis.

So, this may be two questions in one, how have you thought about the experience of physically entering into the process of writing this book as a way of physically interacting with the text and also how has this shaped the book holistically?

JJ: Writers often believe we write with our heads, with our intellect. Yet I think truly effective and affecting poems are written through the body, because rich images and surprising metaphors take complex abstract thinking and bind it to physical sensation.

As an athlete, it’s very important for me to be in my body. Movement—running, biking, hiking, swimming—are much of how I make sense of the world. And so these activities are often the metaphors I turn to. The seeds of “Learning to Run Barefoot” were culled from my first book, for which I went to the high desert of New Mexico and spent a month alone in a canyon in outer Abiquiu to think about O’Keeffe and finish writing the manuscript. I was training for ultra marathons at the time, and I started running barefoot. So in some ways, this poem is simply a description of my morning runs in the canyon.

When I was out there, I was completely alone, five miles away from anyone by foot. I didn’t have a car. I didn’t have a phone. I didn’t have internet. I had my dog and a box of books. That was it. I don’t think many people are really ever that alone in modern life—I know I’d never been. And I didn’t bring movies or podcasts or even music to fill the time. And so when you have that much space, things come up. For me, what came up were a lot of really big questions like, Why am I here? What is the purpose of this life that I have chosen? What would it mean to live well, to live a good life and do positive things in the world? At that point, I was very secular and if you had asked me questions about my identity, being Jewish would have been very far down on that list. I was culturally Jewish. But when I came back from the desert, I found myself looking for wisdom more ancient and more tested by time than contemporary writing. And that’s when I started reading Torah. So that searching was what led me to this moment and to unalone. When I write in that poem, “Give thanks for such falter,” part of what I’m trying to remind myself is to be grateful for the moments that trip us up and bring us to our knees—how new the world looks from that vantage, as well as when you stand back up and continue on, changed, even slightly, by the experience.

AM: I think that’s another loose connective question that I could talk about is I’m thinking about the poems themselves at the level of the line. There’s such an attention to breath and musicality. I have not read as much as you have in the field, but in the biblical texts I’ve read, in Genesis, there is musicality, but not at the caliber of a poet, per se.

I was wondering what you thought about how that changes how someone would encounter the work and how that is an opportunity for a kind of opening?

JJ: I love this question. As someone who has a pretty meh singing voice, poetry is the way I get to make music. And when you really pay attention to the sonic tapestry of a poem, you transform the experience of a reader. Music becomes a means of carrying a message. It can be contrast: you can have very loud sounds with a quiet message or vice versa. I love music and visual art for the immediacy of their effect on us. If I’m moved, say, by a painting I know nothing about, but something about it grabs me and demands my attention, then, hopefully, once I learn more about that artist and the work behind that particular piece, it’s going to even deepen my initial experience. That, to me, is what I’m striving for with a poem. Poetry is meant to be read aloud. So even if someone doesn’t “get it,” whatever that means, I want them to get enough of a feeling that they might be compelled to sit with the poem and let the meaning come.

AM: Lastly, I wanted to ask what you hope readers ultimately will take away from your poetry and how you want that to impact them emotionally or intellectually. How do you see your book functioning in the world?

JJ: Some of the joy of sending a book off into the world is that you never know what responses and insights you’ll receive in turn (like your beautiful question about tzimtzum as a lens through which to read the book). But if I could share anything, it’s how the degree of attention and presence this study called for, as well as the idea of approaching something as sacred—not as an object of critique, which is how in academia we are taught to approach things, but as though it’s sacred and cannot just be dismissed—has honestly changed the way that I walk in the world and taught me new and better ways to be in community. So I hope something people can take from this book is that you can sit with an idea or story or even a person whose presence feels upsetting and even painful, and still ultimately find some moment of companionship and wisdom from that experience of being in relationship.

Whether a reader is actively religious or has been turned away from religion because it’s a site of wounding for them, I hope that in coming to the bible as an outsider, late to the text, and in coming to it as a queer woman, that the poems in unalone might speak to readers and say that whatever your background or current practice, you get to forge your own path into your given or chosen practice, that these texts and traditions are yours, and you get to meet them on your own terms, so that they do not harm or cage, but instead feed you.

–

Jessica Jacobs is the author of unalone, poems in conversation with the Book of Genesis (Four Way Books, March 2024); Take Me with You, Wherever You’re Going (Four Way Books, 2019), one of Library Journal’s Best Poetry Books of the Year, winner of the Devil’s Kitchen and Goldie Awards, and a finalist for the Brockman-Campbell, American Fiction, and Julie Suk Book Awards; Pelvis with Distance (White Pine Press, 2015), a biography-in-poems of Georgia O’Keeffe, winner of the New Mexico Book Award in Poetry and a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award; and co-author of Write It! 100 Poetry Prompts to Inspire (Spruce Books/Penguin Random House). She is the founder and executive director of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry.

Anastasios Mihalopoulos is a Greek/Italian-American from Boardman, Ohio. He received his MFA in poetry from the Northeast Ohio MFA program and his B.S. in both chemistry and English from Allegheny College. His work has appeared in Blue Earth Review, West Trade Review, Ergon, The Decadent Review and elsewhere. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of New Brunswick.