Interview // Like a Trapdoor Opening: A Conversation with Ed Skoog

by Jake Uitti | Contributing Writer

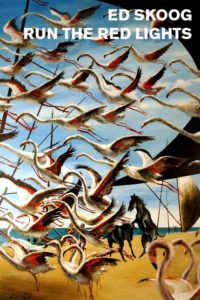

It’s not often you meet someone who is both poet and podcast host, but that’s exactly what you get when you encounter the loquacious writer and Portland, Oregon resident, Ed Skoog. Thoughtful and meticulous with his words, Skoog—who grew up in Kansas and has spent time in Montana and the Northwest—muses on friendship, conversation, death and rebuilding without much prompting. His most recent books of poetry, Rough Day and Run The Red Lights, showcase strength and facility with language while differing drastically from one another in tone, presentation, and form. Skoog is currently at work on his next book, Travelers Leaving for the City, which he describes as “a book-length poem about arrivals and departures, centered around my grandfather’s murder in 1955.” Skoog, who continues to co-host his podcast with John Robert Lennon, Lunch Box with Ed and John, chatted with us about his inspirations, his thoughts of home, and how Hurricane Katrina showed him poetry is essential for rebuilding a city.

Jake Uitti: What joy does the sound of the word “Topeka”—or even the town itself —bring you while writing?

Jake Uitti: What joy does the sound of the word “Topeka”—or even the town itself —bring you while writing?

Ed Skoog: Well, it’s home. I suppose if I was from a different city that made a different sound, I might not name-check it as often. “Topeka” sounds as comic now as when I was a kid. Topeka has all the warm and complicated associations of home, but Topeka also seems like a ludicrous place. Also, a surprising number of Topekans have become writers, and although there’s little common ground, to say “Topeka” connects the poems to the multiverse of Topekan texts, an impossible place that we’ve all visited. It also functions like an algebraic variable, which could also be Hartford or Gloucester or Paterson or Shropshire or Bunyah, New South Wales. It’s my home, and it’s your home, and it’s both gone and never going anywhere.

There’s a lot in Run The Red Lights—I’m thinking specifically of poems like “The Immortals” and “Showering at Night”—about bodies and homes. What significance or drama do these concepts elicit in you?

Form and content are inseparable. That’s the quote from Robert Creeley, right? Form and content are inseparable in poetry, and our experience: there’s a connection between the body and poetic form. The poem and the body both have a concrete existence, and an abstract existence.

And both are mortal, beginning and ending. A poem begins before you sit down to write it, a long time before, perhaps before one was even born. If so, then the poem began before the language it uses, in perceptions. In what we call “poetry,” and poetry is shorthand for a much larger, indefinable thing, there is something pre-human.

When you discover an image like the one of the red light—both as traffic signal and as burning ember of your mother’s cigarette—what happens in your brain? And once you have such an image, how do you unpack it for a poem?

My memory of writing that specifically is similar to the feeling I have of reading it aloud, which is heartbreak. Like a trapdoor opening. When meaningful images rhyme like that, there’s a feeling of revelation and suddenly saying something that was there all along. Rilke says that rhyme uncovers the ancient and terrible connections between words, and I think that’s true for image rhymes, too, revealing the ancient and terrible connections between things.

Much of Run The Red Lights felt like a more straightforward narrative telling, whereas Rough Day felt more abstract, like bursts of images and thoughts. How did you approach Red Lights after finishing Rough Day?

I try to write what I want to read. Around the time of Red Lights, John Lennon and I started the podcast, which brought the foreground the value of talk, not just talkiness. I wanted to read poems that included me in a conversation, one-to-one, instead of a voice in the dark, or from a stage or a lectern. Talk brings out the best in your intelligence and heart.

Can you share one trick about writing you’ve learned over the years?

Stay close to the original impulse that made you want to write a poem. Don’t stray too far from that initial joy.

Your prowess with language is well documented. As a kid, did you read the dictionary page-by-page?

No! I don’t think I did, anyway. I hope I didn’t. I started reading and writing poetry very seriously when I was nine-years-old. Dungeons and Dragons introduced me to a wide vocabulary, too. As did having the textual detritus of older brothers around the house: comic books, sci-fi and fantasy novels, Doonesbury, their Ornithology and Chemistry textbooks. I’m mainly restless, jumping from thing to thing. As early as seventh grade, I’d skip school to go the library. That’s where I wanted to be.

When reflecting on the devastation of Katrina for some of your poems in Rough Day, what did you learn about how you process ideas of destruction?

I observed that poetry had a role in documentation, and in creating an emotional and psychological context for rebuilding. Poetry is very far down on the list of things you need to rebuild a city, but it is on the list. What you need to rebuild a city, must be what keeps it together. We shouldn’t need to flood a city to learn that. I don’t think anyone has accused me of being very radical but Katrina certainly radicalized me to the possibility of the role of the artist to people outside one’s immediate circle. Also that poetry adds to the counterweight against official language.

You write about the Blue Moon Tavern and Café Racer in your work. What role do these Seattle bars play in your writing?

Also Markey’s Bar, The Saturn Bar, The Basement Pub, The Sandy Hut and The Tin Hat. The tavern is where you go to meet your friends and to make new friends, among music and laughter. Some people go to church, I’m told. In my experience, the bar has been where domestic meets public. The bar is also a place of danger, as you indicate by mentioning Café Racer, and the mass shooting there. I’ve lost as many people in bars as I’ve gained. Someone can walk in and shoot everybody. Yet someone might also walk in and give everyone Oysters Rockefeller.

There’s a line in the poem “My Bodyguard” in Red Lights that says, “If you / look someone in the eye / for eight seconds, you’ll / sleep together.” Who was the last person you looked in the eye for eight seconds?

That’s not from direct experience. It’s a guess. No American has ever looked another American in the eye for more than four seconds. We don’t even look each other in the eye when we cheers, and we close our eyes when kissing.

Ed Skoog was born in Topeka, Kansas. His collections of poetry include the chapbooks Toolkit (1995) and Field Recording (2003) and the full-length volumes Mister Skylight (2009,) Rough Day (2013), and Run the Red Lights (2016). Skoog has taught at the Idyllwild Arts Foundation in Idyllwild, California, the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, and Tulane University. He has been the Jenny McKean Moore Writer in Washington at George Washington University and writer-in-residence at the Richard Hugo House.

Jake Uitti is a Seattle-based writer who loves Tony Bennett, Amy Winehouse, and The Black Tones. His work has been featured in the Seattle Times, Washington Post and The Monarch Review.