By Diana Khoi Nguyen | Contributing Writer

Joanna Klink earned an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a PhD from The Johns Hopkins University. Her collections of poetry include They Are Sleeping (2000), Circadian (2007), and Raptus (2010). Her new book, Excerpts from a Secret Prophecy, is forthcoming in April.

What was your MFA like—as a native to Iowa?

It was odd. Because I grew up in Iowa City, I was constantly bumping into people I knew from high school and grade school and The Preucil School of Music—also my parents’ friends. Also my parents. But the Iowa Workshop itself was new to me (the actual Workshop as opposed to the one I’d heard about). It was intense. The faculty were insanely talented and set the bar absurdly high…the other students were insanely talented, some of them certifiably crazy…there was constant creative pressure. We would turn in work every week, but we would also spend hours reading the worksheets from all the workshops, even the fiction workshops. And when a professor recommended a book in passing, we’d go find it and read it. So it was exhilarating and stressful, and sometimes I would walk half-stunned out of class to the pedestrian mall by the public library where I spent so much time as a kid and think, What am I doing here. It was like regressing and having my brain rewired all at once.

When did you know you wanted to get a PhD? Would you recommend emerging poets to pursue a PhD?

I started my Ph.D. before I went to Iowa—I took a leave of absence from Johns Hopkins to go back to Iowa City for those two years. I didn’t know I wanted to get a Ph.D. I just thought I might be happy reading a lot of German poetry, and applied to German Departments without really knowing what I was getting into.

At Hopkins I immediately met Allen Grossman, who was in the English Department, who became my mentor—he was both a poet and a literary critic, with the two vocations effortlessly informing each other. I was impressed by that. By the depth of his vision and his conviction that it didn’t make sense to talk about any single poem without understanding something of the—for Grossman, transhistorical—project of writing poems. (My first seminar with him was called “Poetry: From Sappho to Celan.” When I left Hopkins he was teaching poetics courses called “Hard Problems.”)

Because of Grossman, I moved into the Humanities Center and started reading American, English, French poetry…so that by the time I arrived at Iowa, I wanted to do what he did, I wanted to try to carry these traditions and their powers into my own poems and be able to contextualize the poems I was reading in workshops.

As far as recommending Ph.D. programs—I don’t know. I think a young poet should be in a Ph.D. in Literature if she or he loves reading and discussing texts and wants to be immersed in the history of a genre or idea. I know many super-talented poets who have started Ph.D. programs and quit because they weren’t getting enough of their own writing done—they were surprised that their creative work wasn’t prioritized there. Maybe it comes down to whether or not you want to spend most of your time reading books and writing papers and trying out teaching.

Since you started your PhD first, how did you come to the decision to do a MFA (in the midst of your PhD, no less)?

At Hopkins I was spending time with poets from the Writing Seminars—Dorothy Wang, David Greenberg—and starting to feel at home writing poems. I wanted to be in the company of writers for a while.

Did you have any time between your BA and your PhD/MFA? If so, what did you do during this time?

No, I just rushed from degree to degree. It’s not something I recommend. By the time I started my position at The University of Montana, I was brain-dead, physically exhausted, and delirious from adrenaline (I would like to thank every student in my first workshops in January 2000 who did not drop the class). I wish I had taken several years off to work whatever-jobs or travel.

Instead, after Iowa, I moved to Cambridge, because Grossman was on leave and living in Lexington, and my other advisor, Peter Sacks, had moved to Harvard. I was truly cobbling together an existence—I had some finishing grants from Hopkins, but not enough to afford living in Cambridge, so I applied for some positions and ended up with a job in the Widener Library at Harvard, guarding the Gutenberg Bible. I knew nothing about the Gutenberg Bible. Guarding it meant hovering over a button which auto-dialed the Harvard police. Anyway the job saved my life. I finished writing my first book of poems in that tiny over-carpeted underlit room (which, honestly, very few people ever entered) and drafted the last chapters of my dissertation.

That is so incredible—to guard the Gutenberg Bible! And all it entailed was hovering over a button. Were you ever tempted to press it—after so many hours and days of not pressing it? Conversely, did you every press it due to a real threat?

As far as I know, nobody tried to steal the Bible while I was sitting there. I did manage to lock myself into Widener by mistake…it was during a Harvard graduation and I was supposed to leave the building by noon and simply forgot. I had to press the button to get the Harvard police to let me out.

I’d never want to be locked inside any place—but if I had to choose, a library would be it. Who were your earliest writing crushes?

In college I didn’t read much contemporary American poetry, so at first I loved Rilke, Trakl, Celan. I loved Keats even though some of it seemed gratuitously weepy (this is obviously idiotic). T.S. Eliot.

Neruda. No women.

Then at Hopkins someone steered me toward Niedecker and Bishop, and I couldn’t believe how much force they were able to summon in their voices. Then I started reading Denise Levertov, Linda Gregg, Jorie Graham, and Louise Glück. They are still the guiding lights for me.

As a young person working on her first book, what I always have to ask is: How did you get your first book published?

I sent my first book to contests, mostly first book contests, in that year after graduating from Iowa. I didn’t know what I was doing. In retrospect I wish I had waited at least a few more years to submit the manuscript, because I am embarrassed by the extent to which it is just a heap of stray poems, some of them shameless knock-offs, and not a book. It was taken by Alice James and the University of Georgia Press, and I ended up publishing with Georgia. (There were fewer poets submitting books at that point, in 1999—so much less competition than there is today.)

But it’s easy for me to say that I wish I had waited, or to advise my own graduate students at Montana to take their time before sending out a book—when in the end I wanted to get a job teaching poetry, and it’s nearly impossible to get a job without having a book.

But some of the really great contemporary books—like Linda Gregg’s Too Bright To See—were written across many years. You can feel a different order of time in them. Gregg wrote those poems when she was on a Fulbright in Greece, staring at goats and cypresses, living on next-to-nothing.

If you could talk to a younger Joanna, say, Joanna in her mid-20s, what would you tell her?

To calm down? To be less of an egomaniac and to listen more. To spend more time with people, more time outdoors and on a bike, less time in your head.

Although I’d like to have some of that brazen 20’s ego and conviction now. As I get older—I’m not as sure as I was before.

Do you have any advice to young writers who are struggling now?

It is important to keep finding new books, new poems, new essays and stories—to listen when other people recommend books and to get a library card and to spend whatever money and hours you can in bookstores. You have to put some time into staying inspired, and often one’s own work can start to feel desultory simply because it’s not enough in conversation with other voices.

My colleague and friend, the poet Prageeta Sharma, is constantly mentioning writers I’ve never heard of. I had read some Walcott, but she pointed me to a poem from White Egrets, and that book is now one of my most treasured books. My life would be much smaller if it weren’t for her.

It has also helped me so much to have a few trusted readers with whom I exchange work. They give me immediate frank (the frank part is key) feedback, and keep me from repeating myself or from shooting down an idea before I’ve even given it a chance. I don’t know. Being a writer can turn into such a recessed, private, isolating endeavor if you don’t push hard in the opposite direction.

And for those writers in M.F.A. programs—my advice is to allow yourself to openly admire the writing that’s happening around you. And to risk sounding sloppy and deeply naive, even when you’re about to graduate.

And to pay attention when you find yourself having unusually heated arguments. All of the faculty who taught me at Iowa were extraordinary (I don’t say this lightly), but my best / most difficult teacher was Dean Young. I had always loved his work, but when we had a poem in front of us in workshop, we never agreed about it. We argued every week. He asked me to explain what it was I loved in Bishop and encouraged me, repeatedly, to stop reading Bishop (I think he literally ran off with the book then slipped some Lorca poems into my mailbox). The whole thing was infuriating. Over the years it has become clear to me how much I owe Dean. He helped me define my poetics and (more importantly) he helped me to loosen my grip on having a poetics. Like Grossman, he changed my life.

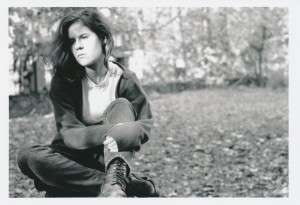

Do you have any young JK photos you wouldn’t mind sharing with us?

Sure.

A native of California, Diana Khoi Nguyen will be the Roth Resident at Bucknell University in the spring, where she’ll continue work on her first manuscript. Her poems and reviews appear or are forthcoming in Poetry, Gulf Coast, Kenyon Review Online, West Branch, Lana Turner, and elsewhere. Currently a resident of Blönduós, Iceland, Diana is sculpting wool and weaving. www.dianakhoinguyen.