Interview // How Did We Come To This?: A Conversation with Heid E. Erdrich

by Jennifer Elise Foerster | Senior Editor

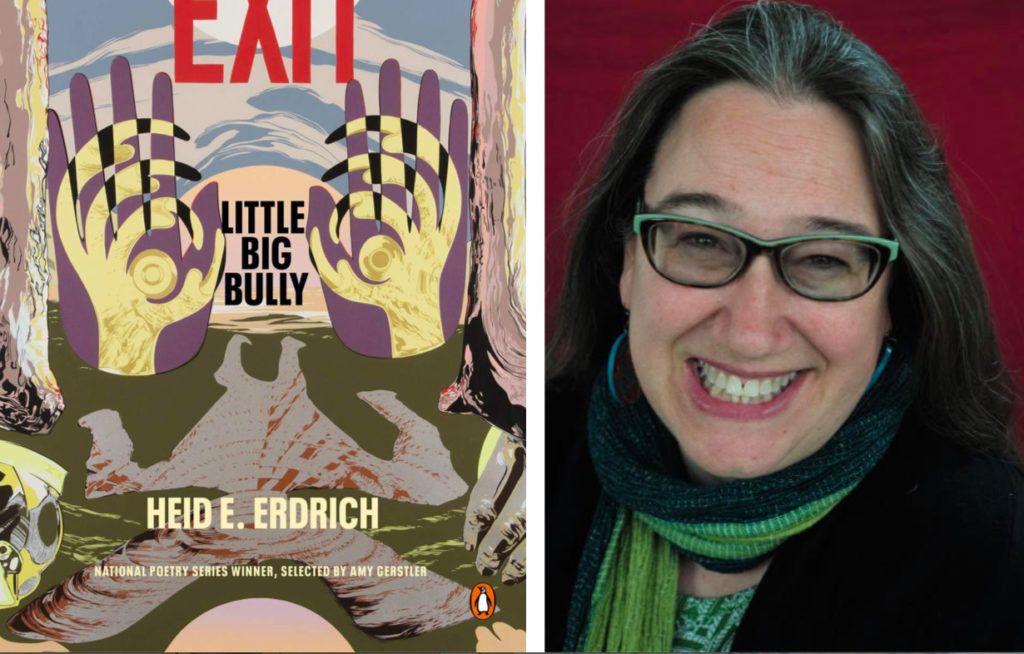

The release of Little Big Bully, Heid Erdrich’s seventh collection of poetry, selected by Amy Gerstler as a 2019 National Poetry Series winner, was one of those rare and special delights of the infamously dim 2020. But there are many other reasons I’ve been anxious for a chance to interview Heid for the Poetry Northwest Native Torchlight Series. Heid is a mentor and friend, whose versatile work as an artist consistently inspires my imagination of what it means to be a poet. When we read together at the 2018 National Book Festival in Washington D.C., I remember a conversation we had one evening as we walked the Library of Congress halls—it was about research and the excitement of investigation. There couldn’t be a more appropriate place to be reminded about archives, and the roles of poets in the continual interrogation, remaking, and engagement with these archives. Heid is an avid researcher with an unbounded energy for discourse, learning, and making—change-making in particular. She is truly multi-modal in her work; as an installation artist working in film and multi-media, a poet, essayist, curator, professor, critic, editor, and performance artist, she explores and communicates the world through a dynamic latitude of professional and creative roles. In addition to seven collections of poetry, Heid has edited two anthologies and written a non-fiction Indigenous foods memoir. Heid grew up in Wahpeton, North Dakota, and lives in Minneapolis. I’m so glad to share with you our conversation from December 2020 and hope you will take the time to further explore her books and video poems here in the 4th edition of the Native Poets Torchlight Series, and by visiting her website and her Vimeo Channel.

*

Jennifer: Heid, how did you come to poetry? I’m always interested in hearing poets’ poetry-origin stories, if you have one you’d like to tell.

Heid: Our Dad loves poetry and at 95 he was still reading poetry. He could recite dozens of poems by heart and when we were kids, he asked us to memorize and recite poems. That was entertainment in our little prairie town. In 6th grade a Poets-in-the-Schools program did a residency with my class. I felt pretty successful with my attempts at poetry and began keeping a poetry journal. By the time I was in high school, I was submitting to contests and trying to publish my work. My first real publication was in Sun Tracks magazine from University of Arizona.

We are all lucky for what you bring to poetry today. You’re not only a prolific writer but also a generous curator, editor, and teacher. With seven poetry collections as well as non-fiction works and multi-media and collaborative art installations, you are also continuously working at curating anthologies and promoting the works and art of your contemporaries. Sister Nations, New Poets of Native Nations, and the most recent When the Light of the World Was Subdued Our Songs Came Through, are each ground-breaking presentations of the works and writings of people from today’s Native Nations. New Poets of Native Nations, which won an American Book Award, was especially seminal, highlighting 21 poets of Native Nations whose first books were published after the year 2000. As you wrote in your introduction to that anthology, the collection sought to introduce new poets “from dozens of distinct cultures,” who present “a vast diversity of literary approaches and national stances” to new audiences “who might then start seeing actual Native-created poetry as part of the larger American poetry conversation.” Your editorial work has been pivotal in the changes we’ve seen in the last ten to twenty years in the increasing recognition and inclusion of poets of Native Nations in our national literary conversation.

Editing is a kind of service I really enjoy—it gives me a place to share what I value, learn about new writers, and to teach in a broad way. I was stunned at the eager response to New Poets of Native Nations, but not surprised that so few people had read numbers of contemporary poets who are Native in one place. That gap, the lack of a truly current book of poets who are Native, was exactly why I edited the anthology.

Here at PNW, one of our central missions is to continue this celebration and recognition of Indigenous poets by providing a platform for their work. This year we are inaugurating the James Welch Prize, which will honor, annually, two poems and two authors of Native American Nations with a reading, prize, and publication. I’m so glad that this interview with you will coincide with the launching of this literary prize.

I admire how seamlessly you speak with multiple modes in your poetry—pop culture (from zombies to fries), technological portals (coding and cyber space), media icons (Superman, Elvis) and also contemporary politics and media (quoting from news sources and current events reporting). It seems to me that poetry is a way you can speak through and with our shared public world—can you speak a little about poetry and how it speaks with, from, or to our contemporary society and culture(s)?

That is so kind of you to notice—I’m a pretty introverted person, despite my ability to perform to a crowd, and that Emily Dickinson poem about writing to the world that never wrote to me really resonates. I get that sense of the news, the currents of cultural consciousness, from many of the poets I read and I write back to it from my own place. I get a sense of the pop world from my kids (who are young adults now) and from working with a lot of different kinds of people. The textures of humanity really interest me.

It Was Cloudy from Heid E. Erdrich on Vimeo.

I see such an engagement with current cultural and social consciousness in your work, which I also see as a kind of activism. Do you see activism as part of your work as a poet, and in general, as a person?

Taking on the label activist has never been easy for me as I’ve known the most amazing political and community organizers who work on the streets or with the state—they are real activists. Right now, I don’t feel active enough to claim that label. I’m cowering from Covid-19 while a protest movement spreads globally having begun when George Floyd was murdered by police quite close to where I live. It’s not that I doubt my work has an activist stance, it does especially in terms of women’s and larger Native American concerns. Sometimes my work intersects with environmental concerns as well and museums have become the site of my interventions. Lately I have been considering that my work with Native youth, students, artists, writers and my editorial work might be my most meaningful activism.

I absolutely agree—just this past November when you were guest editor for Poem-A-Day with the Poetry Foundation, you highlighted a wonderful selection of Native poets. I see you as a poet who works for and with community—sharing space, creating space, and mentoring so many young writers. Your video work and multi-media/multi-genre engagement also speaks to this commitment to collaboration and to creating art through meaningful relationships.

Collaboration allowed me to turn my work outside myself for a good long time and I am so grateful to the artists, choreographers, filmmakers, and others whom I was lucky enough to work with in the past dozen or so years. Leaving fulltime academic teaching to work with Native American artists as a curator became a kind of collaboration as well and perfectly allowed me what might have been a lonely transition from academia to a gig life.

I’d like to talk about your latest book, just released, Little Big Bully. This is an incredibly exciting collection. The book opens with the engrossing, heart-stopping poem, “How.” The litany of “how,” coupled with the absence of punctuation and lineation, creates a breathless urgency to the questions that infuse Little Big Bully: How do we love? How did we come to this? How do we heal? Is it possible to heal in a world that is made, it seems, of conflict, of abuse? The anaphora introduced in this poem becomes a touchstone device throughout the book. This repetition achieves so much – it sets up a series of negations that illuminate what something is by what something isn’t, as in the poem, “Not.” It also controls rhythm, building tension and emphasis. What are your thoughts about how and why this craft device underpins so much of the book?

Repetition and anaphora do create what I hope is a breathless quality to the utterance and what I hope is a kind of headlong feel, a tumble that lets it all out. To me, the distracted mind, the disturbed mind, the excited mind, the mind in ecstasy, in love – they all create repeated thoughts and wishes. If the past few years were not exactly that, I might have heard another voice. These sounds come to me whole – it’s not always a choice. Listening is the element of craft here – listening to your lines as they come. Don’t ignore the echos.

I love the idea of listening as an “element of craft.” Your book displays such a diversity of craft choices. I noticed, for example, how you featured the caesura, which seemed to allow you to modulate the poems across/down the page, forming a unique kind of punctuation, grammar, and musicality. The prevalence of the caesura in controlling the lineation and choreography of the words also allows, in many instances, for the emphatic repetitions and stutterings, which are the very real utterances of human anxiety, question, and wonderment. I enjoyed reading these poems aloud, and felt the arrangements guided me in hearing the meaning, tone, and intent beneath the poems.

For sure I sensed most of what you suggest—the held breath, the hiccup of a caesura working to suggest anxiety. This book came from a time of global anxiety, so there we were or here we are, all pausing slowly and looking into the next blank future. And yes, white space is meant to work as both visual punctuation and as breath script for reading. I was not sure people would understand as they read it, but I’ve been surprised. Isn’t it great when we are read as we hoped?

The reflexive is another brilliant concept and form employed in this book. Poems like “Fauxskin” engage the grammar of the reflexive as well as the project of reflexivity/reflection. Do you feel you were creating, through this book, a grammar of the reflexive or of relativity?

I’m amazed by this question as I have often wished for more reflexivity in English. Languages like my Indigenous language Anishinaabemowin do a better job at speaking reflexive states – relational states. What would our lives as humans be if we spoke in relation to living others? Would we have less conflict? Could we stand more contradiction?

I’m especially moved by the struggles with complicity that so many of the poems embrace, asking, who is the perpetrator and who the victim—who is the “us” and who are they? Who belongs and who doesn’t and what are the violences inherent in the construction and trespassing of these boundaries?

A huge part of my consideration of complicity in these poems comes from wanting to understand how harm works, how we become vulnerable. What lessons are within us? How else can we resist if we don’t understand how the abuser works? How do the people who support abuse become who they are?

This persistence of questioning is something I am grateful for throughout the book. I relate, I think we all in many ways relate, to the questioning of our complicity in the state of the world, in our past, present, and future. This book doesn’t take an easy side; it stands in all sides, in the little and the big, in the bully and the lover, in the child and the mother, the colonizer, the indigenous, the human, tree, animal, weather, writer.

Thank you for this depth of reading—I often don’t notice how far I’ve ranged with the poems in a book unless it’s pointed out. This book is different in some ways—I tried to understand perpetrator and the person harmed. I tried to understand how people who stand beside bullies can make that choice. Honestly, it was driving me mad, trying to understand why. I’ve always been attracted to poems that pose questions and not as much interested in poets who make pronouncements. These poems of mine ask questions because they are, on a personal and political level, a record of survival in a time of conundrums, threats, and re-positioning relationships.

Od’e Miikan-Heart Line (Moose version) from Heid E. Erdrich on Vimeo.

What is your story of the making of this book? Was there an inciting moment, poem, or experience that birthed this book?

A few of the oldest poems come from 2014-2017, when I saw folks treat each other with a lack of respect on social media, when I saw the depth of divisions among Native people—what brought us so low? Most of the poems, however, came together in the first month of 2019 when we were housebound during the polar vortex. That isolation is not unlike what we feel in Covid-19 times and I think that resonates now. We were unable to leave the house for 5 days straight—too cold and too much snow for 10 days solid. We didn’t know it was coming a year later—the lockdown and pandemic—but we had some preparation in those deeply cold and lonesome days of 2019.

I’m not sure it’s the poem that birthed the book, but “How” became the first poem in the book and important to its shape. At some point in writing over three years, I realized I was trying to answer that poem: How did we come to this? As you suggested, or maybe a step further, the book is organized around asking and answering.

I admire how the book boldly evokes such a range of emotions—from anguish to humor—the satirical, the mythic, the personal, the political. And through this journey, the center holds, and the center seems, to me, to be the persistence of conflict, the absence of certitude, how there are so many “variations of true” (a title of one of your poems) in our human experience. We are the colonizer and the colonized; we are nature and we struggle with our separation from nature, or whatever “our” nature is—violence? love? are these ever inseparable? Of course, I’m not articulating this analysis very clearly; that’s why this concern is best articulated and explored, I believe, through poems. And your poems do this profoundly.

Thank you for all that you have brought to us through your art, Heid.

Miigwech, Jennifer! It’s a sincere pleasure to have you, one I admire, read my work.

This interview and the following poems are the fourth in a regular series edited by Jennifer Elise Foerster.

Heid E. Erdrich grew up in Wahpeton North Dakota and is Ojibwe enrolled at Turtle Mountain. Her new poetry collection Little Big Bully won a National Poetry Series award in 2019 and was published by Penguin in 2020. Heid edited the 2018 anthology New Poets of Native Nations which won an American Book Award. Heid’s work has won awards including a Native Arts and Cultures Foundation Fellowship and two Minnesota Book Awards for poetry. Heid teaches in the low-residency MFA Creative Writing Program of Augsburg University. She is the 2021 Glasgow (virtual) Visiting Professor at Washington and Lee University.

Jennifer Elise Foerster is the author of two books of poetry, Leaving Tulsa (2013) and Bright Raft in the Afterweather (2018), both published by the University of Arizona Press. Jennifer currently teaches at the Rainier Writing Workshop and is the Literary Assistant to the U.S. Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo. She received her PhD in English and Literary Arts at the University of Denver and her MFA at Vermont College of the Fine Arts. She is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship and was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford. Foerster grew up living internationally, is of European (German/Dutch) and Mvskoke descent, and is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma. She lives in San Francisco.