Interview // Fruitful and Dangerous: A Conversation with Lawrence Lacambra Ypil

by Jaimie Li | Contributing Writer

“How does one once again speak truth to power here?” I return to these words from my interview with Lawrence Lacambra Ypil amid surging and underreported violence against Asian-American communities—and in the immediate aftermath of last week’s anti-Asian hate crime in Atlanta—and find them more urgent than ever. Ypil is the author of The Experiment of the Tropics (Gaudy Boy, 2019), a collection of lyric essays that was named a finalist for the Lambda Literary Awards and was longlisted for The Believer Book Awards. Our discussion examined the importance of foregrounding Asian perspectives from a country interrupted by American occupation at the turn of the 20th century, repurposing the English language and literary tradition against that “fragile empire,” and “writing not just for freedom, but from it.” The resulting interview was conducted over Zoom in May 2020 and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You grew up in the Philippines and now teach in Singapore. How did studying in America inform your latest book of lyric essays, The Experiment of the Tropics?

The very first pieces from this book came to me towards the end of my stint studying nonfiction at the University of Iowa from 2014 to 2015. I was interested in the time period spanning the American occupation of the Philippines between 1898 and 1946, and in the U.S., I got a strong sense that this part of American history is not always remembered. The occupation of the Philippines is a little footnote—unless you’re Filipino—in the American historical imagination. I wanted to return to that period with a sense of recuperation. I kept writing these pieces when I moved to Singapore to teach poetry at Yale-NUS, and I wrote a lot of them when I would take trips to my home city, Cebu in the Philippines. This book was written in at least three places.

By the tightness of a tie, the looseness of a stance, / a man is measured. If you can’t walk straight, dear sir, / at least sit straight.

from “I Could Say,” Lawrence Lacambra Ypil

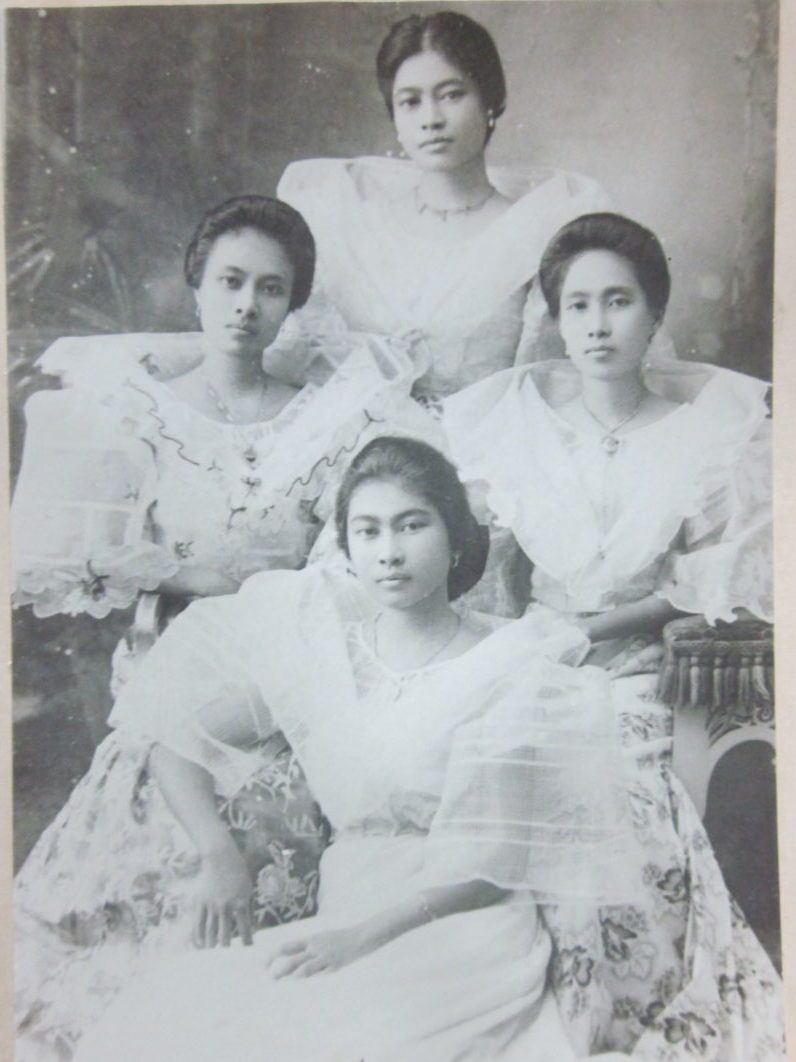

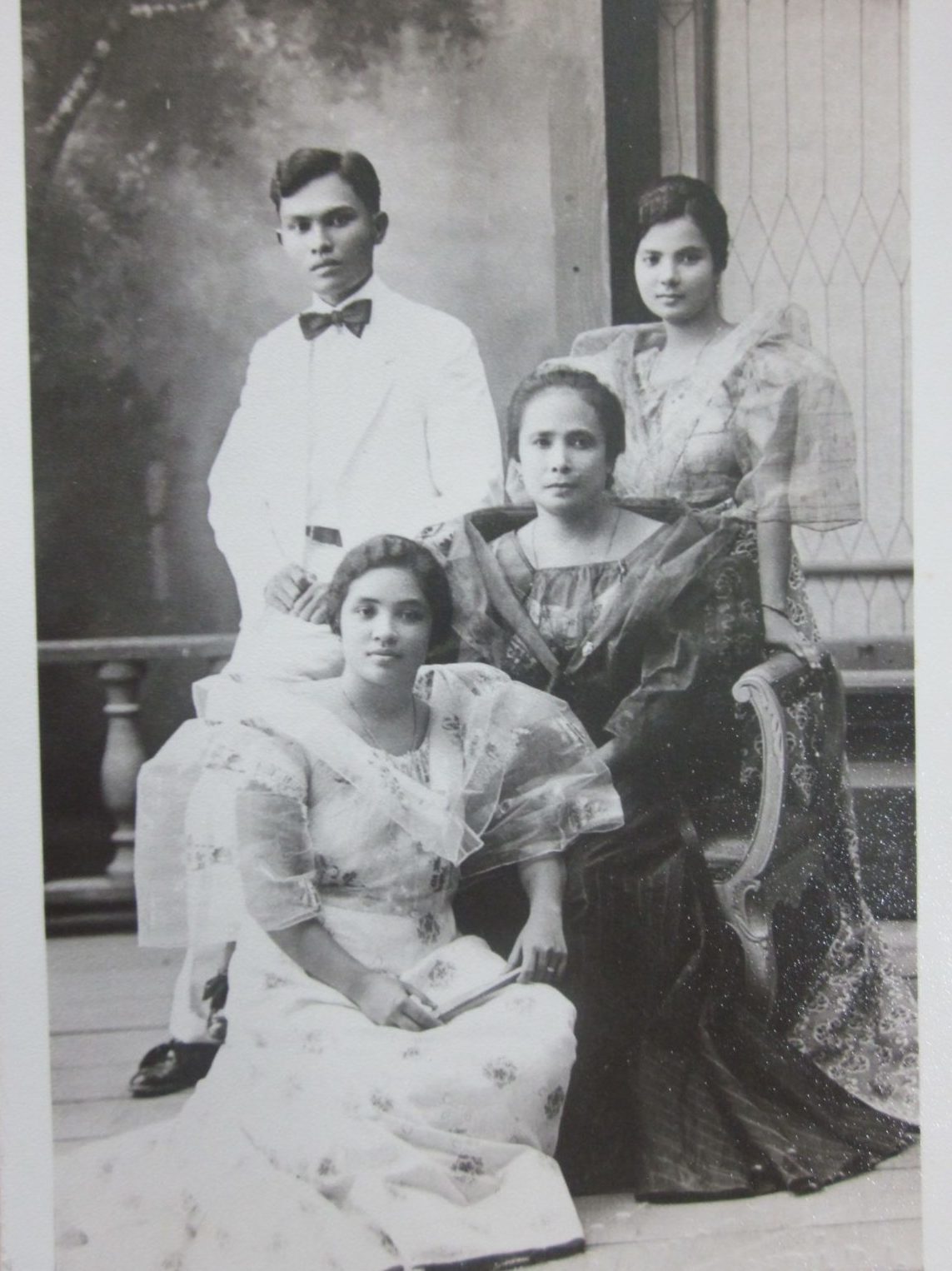

The book notably features a series of black and white photographs from the archives of the Cebuano Studies Center at the University of San Carlos. What drew you to them?

A lot of this book came from my love for the potentially problematic archival photographs of the Philippines in the early 20th century. Each is more beautiful than the last, as many were studio photographs from mostly wealthy families. I kept this in mind as I was looking and writing: they came from a particular social class, and this fantasy of ease and beauty and power was performed through the photograph as well as imagined. I was leading with a history of fantasy inasmuch as fact. Part of the joy was acknowledging that the history of the imagination is fraught with human frailty and human failings, but also human desires. It’s the desire for money, the desire for security, and the desire for peace, all tied to the ability or inability to fulfill them that one may or may not have in a particular historical moment. History is knowing that one receives not just what happens, but what could have happened, what we wish could have happened, what did not happen. These precise areas are so fruitful and dangerous to write about, and it was, for me, an experience of allowing the eye to roam over history: What does it mean to let the eye linger? Where will it go? What will I see? In a certain way, I had to trust that an early 21st century eye encountering with these early 20th century images had something of value in itself in addition to my eventual research. I was, at some point, interested in who the people were, and, at another point, completely uninterested in who the people were. The encounter in itself was important.

Did your encounter with the photographs affect your writing process?

It became a very physical experience for me. I would carry print-outs of these photographs and my writing pad. In Singapore, I would stay in hawker centers, editing and writing these poems in the midst of these very noisy, drunk uncles who would already be drinking at high noon. I wrote most of them by hand initially. I would give myself an exercise: write until the end of this pad of paper. It was as simple as that. There were days where good things came out and there were others where . . . nothing. But that’s what kept me writing in those days. I remember working on them and literally just wondering, how far could a sentence go?

You called the photographs “potentially problematic.” What was your approach when working with certain outmoded forms of documentation, assumptions, and beliefs?

I came from studying nonfiction as well as poetry, and so I was interested in not only the images but also prose styles from the period of the American occupation. I was particularly drawn to early 20th century anthropology and the kind of beautiful, racist, problematic writing that we find there. I found that to be a really wonderful problem: what they’re saying is completely repulsive, and yet these sentences were beautiful. The poet in me—the reader in me—could not help but appreciate that beauty in the language. And in a certain way, I kind of wanted to try it out. This book is partly a way of trying out that voice of anthropology, which is a certain way of writing the passive omniscient, as a way of understanding the lyric essay or lyrical prose. Maybe part of the thrill is extracting that music and using it for completely different or opposite purposes. Whereas they might have been used to categorize—to dehumanize—I felt that there was something in that voice, that compels the use for completely opposite reasons: to re-humanize and to make it complicated.

What is the relationship between the history of the Philippines and its literary history?

The American occupation at the start of the 20th century is an important part of Filipino literary history because it marked the end of Spanish writing. It also established the public education system in the Philippines, and the teaching of English language and literature was such an important part of that fragile empire. Initially, when English had only just begun to be taught, there was a wonderful resurgence of vernacular literature and a golden period of vernacular journalism—newspapers were written in Cebuano and other local languages. Then, the first Filipino writers in English started to emerge in the early 1910s, until by 1915 or 1920, English found its foothold, especially in the upper classes, which were the educated class. It took predominance over the local languages by the 1930s. For the past two years, I have taught creative writing from the point of view of Filipino literature from this period. An important part of that body of work is imitation: a lot of Filipino writers imitated American and British authors and studied a certain tradition, the way a genre moved. However, they were not only imitating but also inventing and innovating. Writing is really about freedom: freedom in the context of colonization and imperialism, which means learning how to write under those conditions. We write from freedom. We write for it, but from it, also.

The relationship between imitation and innovation reminds me of how the layering of both national and personal identities demands a constant negotiation of what to take forward and leave behind. How do you navigate this complexity as you write?

For me, it’s been a matter of revisiting the past as a way of encountering the hopes and dreams of an older generation for you, whether one likes it or not. A lot of my aunts were public school teachers, and I don’t think any of them were writers. As far as my own decision to write—to almost promise that I would—I felt privileged enough to pursue something that I knew they could not because of the circumstances. There’s a certain sense of responsibility that I feel in relation to that kind of lineage. I grew up in Cebu, and my parents grew up in the same hometown around two or three cities north of it. A good part of my growing up had to do with visiting their hometown and the house that was built by my grandparents. The past was a house that one could visit, and those visits really shaped my sense of where I come from and what kind of stories I received. It’s still there, and I try to visit it every time I’m back home.

I would like to thank the designer of my dress / for the ribbon around my chest / so in the event of any future misdemeanor, / I will have the luxury of an apology / with a flower on my heart.

from “Farewell Goodbye but Not Really,” Lawrence Lacambra Ypil

I can relate to having people in your family who did not have the opportunity to be writers, and that brings to mind how I was struck by how you spotlight socioeconomic strata, particularly in the poems “The Extent to Which Someone Else’s Labor” and “The Erotic.” Did you intentionally set out to deal with this as your subject?

That’s a layer that’s not always picked up! I think the other layers of the book, such as the tensions between American history and Filipino history, are easier to pick up. Social class is where things get really complicated, and the closer you get to it, the more complicated it is. There is an ultimate benefit to keeping things at a distance: things are clearer. This is especially true to the type of history that I’m looking at. In this history of colonialism and occupation, there is a tendency to call things black and white and to imagine that the enemies and the bad guys are one and the good guys are another and that there can never be any switching of sides. It’s very easy to say that the imperialist and the occupation is the true enemy in all of this, but the closer you get to listening to the stories and reading documents from the time period, the more you realize how much collaboration transpired between the native elites and the colonizer. There’s a certain sense that it takes more than two people to tango. The story of social class is the story of power. History is also the story of power. It was important for me to include the recognition of and sensitivity to social class. I don’t know if I consciously did it or if I was just naturally drawn to the layers of grey areas that I was beginning to see in the material.

In “To the Extent of Someone Else’s Labor,” I highlight that the beautiful dresses worn by the women in a photograph were made by someone who may or may not have been made by the women wearing them. Maybe these dresses are part of a whole system of labor that is very quickly erased because it is not documented in a photograph and so does not get archived in the city. As for “The Erotic,” it’s a rare moment when I bring the poem to a more contemporary present moment. The narrator lives in a time closer to ours, but he is also infused with a certain sense of history of labor and inequality that, for him, manifests as a kind of desire. There’s a recognition that sometimes money becomes a way of fulfilling desire, or that there is the dream of money as being something that could fulfill desire. In this case, erotic desire. And, to a certain extent, there’s also a recognition of the failure of that enterprise.

On the subject of desire, the eponymous poem “The Experiment of the Tropics” seemed to me so much about consumption, particularly the consumption of Americanness. What does that concept encompass?

When I read the literature from the period when America occupied the Philippines, there’s a lot of thought and distress about the type of material that the American empire is supposedly to have brought to Filipino culture. The soft drink, the bagged good, the consumable—there was the dream that certain kinds of desires can be fulfilled by these objects. The American dream was a construct transposed onto Filipino history. It included a value for labor—such an American value—that occurs simultaneous to the reverence for the product. That is to say, the object. And there’s something interesting about the possibility that these desires can be fulfilled through consumption of, for example in the poem, a biscuit, because one was doing well if one had access to those things.

Who were the writers documenting this supposed or actual cultural shift?

Manuel Arguilla and Arturo Rotor were tracing the transition to modernity and progress that was happening at that time period. Arguilla is a wonderful documenter of the rural life, and he had a strong sense of how a landscape could shape the figures of our dreams and desires. Rotor’s stories are a bit more urban, and I remember teaching them side by side. It was interesting to me how well the characters interacted with the space and how the space shaped how a character would imagine who he could be, where he could end up, and who he needed to be or be with. Those spaces are quite different, and the notions of fulfillment and fruition are very, very different in a town from a city. Being sensitive to that difference is important to me.

As regards spaces that might shape “who he needed to be or be with,” congratulations on The Experiment of the Tropics becoming a Lambda finalist!

Thank you! I feel very seen by that.

Would you say that writing this book was partly labor-oriented and/or object-oriented?

There are the initial, conscious reasons for writing, and then, much later, the sense that the writing could become a book. We can be occupied too much by a “work” mindset at the start: before there are even any words yet, we’re already thinking about the book and whether it’s a book of poems or a book of essays. While that is perfect for progress and advancement and bettering oneself, I sometimes feel it’s not healthy. There are certain things that can only be written about only if we don’t think of the masses. That’s very rare because I think we live in a time and a culture where it’s not real until there’s a product. As in, if the writing doesn’t lead to the work or a book, then it’s almost like, “Why are you writing to begin with?” I do feel that they are two very, very different processes. I find it most fulfilling when I’m able to catch myself in those very rare moments when I’m not thinking about making a book or writing a poem and instead just in that very rare wonderful space of, “Oh my god, I’m writing!” It’s so rare because we are made to be very conscious about career, and identity, and like, “What’s the next thing you’re working on?” Whereas, I think that very interesting things can happen in those moments when those are not our concerns.

A family is only as good as the father / who is gone. A brother / with a son. A daughter who is only / as good as a vase of roses / which meant very good.

from “The History of Towns,” Lawrence Lacambra Ypil

Speaking of genre, you’ve described this book as a collection of lyric essays, and yet we’ve referred to the pieces within it as poems. How do you distinguish between the two and decide which form works best for your purposes?

Part of the reason why I moved to Iowa to study nonfiction after studying poetry at Washington University was because, at that time, I was quite discontent with contemporary poetry. While the fragmentariness of contemporary verse opened up certain avenues of speaking, I felt that it prevented a kind of commitment and follow-through that I felt only a sentence could give. One can be simplistic and say that I might have just been missing the sentence. But I do remember that wonderful, confusing, and really lovely moment when I honestly could say that I fell in love with the essay. It was a form I felt that I could be relaxed in, that I could be funny in, and that I could breathe in. There’s a certain seriousness that I give to poetry, and the essay as a form really allowed me to relax. As a type of karmic backlash, these essays that I was writing actually in the end also became poems. The Experiment of the Tropics is considered a poetry book, which might be poetry’s way of getting back at me and saying, “You thought you could say otherwise, could you?” There’s a sensibility that poetry really gives you as a writer: attention to the language, possibilities of form, the brashness of insisting, “Nope! I’m not going to give you that nice little narrative resolution that I know you thought I would give you.” Or, “Nope! We’re going to stay in this wonderfully ambiguous moment and we might not know when or how it will end, and that’s all right.” The permissiveness and open-endedness of the poetic spirit is so valuable when brought to the essay form, which I feel can get too embroiled with the need for that insight or that pressure for something to happen so the essay can end. The poem always says, “Nothing needs to happen, but things can change.” That’s where it really can be interesting, where the fulfillment need not be through narrative. I feel like I’m speaking in tongues right now! I’ve never thought about it in this way before, but I love both of those forms.

Your point about a non-narrative resolution reminded me of the last two lines that I love from “There Is a River”: “A daughter smiles, her foot in the water on a stone because she has been / told all her life that she is beautiful, and she believes it.”

I feel like a narrative impulse would automatically want to know what happens to her. “Oh my god, did she fulfill her dreams?” or “Oh my god, where does she go?” Whereas a poetic impulse might be already satisfied with the recognition of that belief. Whether that belief is eventually found to be false or true. This admission of one having heard something before and perhaps having believed it for the rest of one’s life is a kind of poetic recognition fulfilling in itself.

‘I never lived to see’— / which did not mean that I had died / before the city had a train / that would have allowed me / to cross the length of an island / and stare at the sea / but there, there I stood.

from “The History of Towns,” Lawrence Lacambra Ypil

You co-edited the anthology We Might as Well Call It Lyric Essay. Can you speak about the impetus behind the project and how it’s evolved?

That book was the product of a class at Iowa given by John D’Agata as a way of commemorating the anniversary of the first time he published lyric essays in The Seneca Review. We read and chose the top ten or fifteen lyric essays that it had published in the past, and interviewed the essayists that we had chosen. I had the privilege of writing about and meeting Eliot Weinberger, which was wonderful. I was in Iowa until 2015, and things in America have changed since then. I’ve been thinking about the viability of the lyric essay at this current moment in the world. The impression that I get when I talk to my classmates from the program is that there’s a strong need for politically driven writing in the nonfiction landscape, and rightfully so, but it’s put the lyric essay in a weird space. Do we have the patience and the mindset for the lyric essay at this time? Or is this one of those times where lyricism and ambiguity is not what we need right now? I could be wrong, but it seems that there is a strong need for decisiveness—a kind of explicitness of where one stands.

As for me, decisiveness has never been a strong quality that has drawn me to a piece of work. What I have found most beautiful in the essay form has always been its capacity to nurture a sense of digression and to encourage a certain distraction and the kind of revelations that can come out of that lingering, passing gaze. This is not to say that the decisive stare is not beautiful, too. Maybe we live in such a moment where we need those decisive stares. Maybe in a time of war, people need to be clear. And maybe we are not in a time of peace, because it’s only in peace where the beauty and ambiguity or digression and uncertainty can be appreciated. Right now, in the Philippines, there is a growing concern for censorship. It’s interesting what only a few years can do because the Philippines has always been known to be a champion for the freedom of speech, especially within the region. It’s a very important moment to understand where language can take its ground from again. How does one once again speak truth to power here?

Right! How do you proceed at this impasse between digression and decisiveness?

For me, the most memorable interactions with people have been those moments when a certain amount of transformation was possible on both their end and mine. When you understand that you’re meeting with someone who is willing to be transformed and you enter into that space hoping to be transformed—those have been the most interesting friendships. I feel like without that even possibility of yourself being transformed by the moment then there really is no point in encounter. That is no longer encounter; that is something else. It is that encounter which we all need to aspire to not only with other people but also in our texts. To understand that one enters into the writing not because one is clear on what one says but because we are willing to be transformed by that process of writing. That is where the real magic happens. We’re each contending with what we have to contend with through our own spaces. The people pleasers will find it very, very difficult. For those of us who grew up wanting to follow the rules, it takes a lifetime, you know? You want to be a good boy or a good girl or a good person, but then you know you’re not entirely a good person so just own up to it. What’s so hard?

That reminds me of a reviewer who once wrote that your poetry “dares to familiar in the context of the kind of poetry that continues to tell people that it is a form that’s too difficult, a cultural product that’s only for the educated and the elite, the ones who speak in English and are from urban Manila. Ypil’s poems refuse this question of easy or difficult and instead given the limitations of the languages . . . invites the reader into what the poem looks at and says, ‘Come here, this is what you might see differently, or might see now.’”

Wow—that kind of personal perspective is important for me always to nurture, especially with students. Where there’s tradition, power, or hierarchy, we are made to think that there are proper ways of saying things. For example, as a writer, you think, “I want to really write a good essay or a good poem.” That sense of the “good” is really coming from a certain education and/or tradition. Then there’s that moment when, say, no matter how much you want to emulate the essays of E.B. White, you just could not do a “Once More to the Lake.” It’s only in retrospect where you realize there was never really any reason you could have done a “Once More to the Lake.” You did not even grow up beside lakes! That’s where a lot of the work of improving as a writer really comes: when we are finally able to, either out of strength or just exhaustion, say, “Nope! There’s no other way I can say it except in this way.” It takes time, and sometimes it can’t be taught. The classroom can be a space where people begin to express, to feel, and to experience that, but it takes years to reach a point of, “Oh, there isn’t one way.” That’s part of the difficulty of writing creatively. You realize, “Oh, I’m meant to find my own way.” And, then, “Oh, shit!”

—

Lawrence Lacambra Ypil received an MFA in Nonfiction from the University of Iowa and an MFA in Poetry from Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of The Highest Hiding Place and The Experiment of the Tropics. He teaches creative writing at Yale-NUS College in Singapore.

Jaimie Li is an MFA candidate at Goddard College and the recipient of the 2019 Goddard/PEN North American Centers Scholarship. She teaches creative writing workshops on family stories.

—

All images courtesy of the Cebuano Studies Center at the University of San Carlos