Interview // Deborah Woodard on the Poems of Crysta Casey

By Letitia Cain | Business Manager

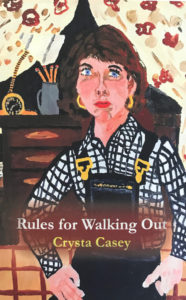

On Saturday, June 10th, Open Books will host the book launch for Crysta Casey’s second posthumous book, Rules for Walking Out (Cave Moon Press), the story of her life as a Woman Marine and vet. I spoke with Deborah Woodard to learn more about Casey’s life as a citizen poet: how she worked as a journalist for the Marines until her honorable discharge in 1980, how she lived with mental illness and received treatment from the Seattle VA, while increasingly dedicating herself to her poetry and painting.

You first met Crysta Casey at a writer’s conference at UC Santa Cruz in 1979 and then became reacquainted with her in a Hugo House class that you taught in 2003. As her literary executor, what role did you play in her most recent, posthumous book Rules for Walking Out?

Crysta’s Casey’s literary estate is also administered by Esther Helfgott and George Stamas, and we all worked on selecting Rules for Walking Out (RFWO) and preparing it for publication. Currently, my focus is on promoting the collection, as, in this political climate, her story needs to be told.

How was Rules for Walking Out compiled; did Casey help with the selection of the poems and/or the ordering? If not, how did you decide which poems to include, in what order and how to represent the different phases of her life? Did you see stylistic changes or patterns in her work while compiling this book that surprised you?

Crysta had been working on compiling RFWO for some time, probably for the better part of a decade. The collection was initially called Battlefield, or Battleground. I remember her coming up to me after a Hugo House class and showing me the manuscript, the title written by hand in printing that sloped slightly down the page. Crysta wanted someone to take a look, and I suggested Sherry Reniker. Not long after that, she called me up and said, “Guess what? Sherry’s a genius of an editor.” It meant a great deal to her to have that support system. In any case, Crysta compiled the collection on her own, with the sort of tweaking from editors that occurs during the normal course of things. Her website was a little unclear on this point, so our apologies! RFWO was the last manuscript that she was able to complete and revise to her satisfaction. When we had the opportunity to bring out a second posthumous collection, thanks to Doug Johnson of Cave Moon Press, it was the logical choice.

For the most part, I’m struck by how consistent Crysta’s style remains throughout RFWO. She may have written early drafts of some of the boot camp poems way back in 1979 at the conference where I met her in Santa Cruz. As I mull over your question, though, it now occurs to me that the sequence of prose poems in the “Green Cammie” section comprise a kind of portrait gallery, with the block of the prose poem approximating a canvas.

Did Casey come up with the title, Rules for Walking Out, in her final manuscript?

Lana Hechtman Ayers came up with the fine title.

Casey published her first poetry collection in 1993—how does the current collection compare in style, tone, theme, content and voice?

Heart Clinic, Crysta’s first book, spotlights what would turn out to be a short-lived marriage. The collection keeps the door open to the possibility of a “normal” life away from institutions. Cooking, flowers, sunbathing, a favorite rocking chair all come into view, however briefly, all fueled by the sheer momentum of youth. But Heart Clinic opens with the tale of the girl next door who spends her life in an iron lung. Talk about a harbinger of confinement!

RFWO is a much more thematically and stylistically unified collection. It takes us through the trajectory of Crysta’s life as a Woman Marine and then as a vet, who, partly because she was abused in the military, is dependent on the VA hospital, its doctors and social workers and the pharmacy where she takes a number and waits to fill her prescriptions. She makes friends on the psych ward and bonds at a particularly deep level with her peers in a smaller break-out therapy group. Slowly, she heals and spends more of her time out in the community, often in company of her peers from the VA.

RFWO is a much more thematically and stylistically unified collection. It takes us through the trajectory of Crysta’s life as a Woman Marine and then as a vet, who, partly because she was abused in the military, is dependent on the VA hospital, its doctors and social workers and the pharmacy where she takes a number and waits to fill her prescriptions. She makes friends on the psych ward and bonds at a particularly deep level with her peers in a smaller break-out therapy group. Slowly, she heals and spends more of her time out in the community, often in company of her peers from the VA.

RFWO is about being institutionalized, but also about how, in time, one can walk out from the institution, and still feel relatively safe. One might even come up with one’s own rules, or tenets, for this walking out. RFWO opens with Captain Bowman’s taunting Crysta with the brig or the psych ward and concludes with her dream “of men / hanging for the crime / of being, a crime they didn’t mean / to commit.” Captain Bowman is merely a cog in the wheel of the institution, and Crysta comes to understand that, along with her other portraits, she has to complete a portrait of the institution itself, and the existential crossroads to which it brings the individual. This is why, for me, RFWO is Crysta’s most mature and ambitious work.

Casey’s website shows that she was also a painter, and two of her books (Rules for Walking Out and Green Cammie) use her paintings as book covers. How was the painting selected for Rules for Walking Out? How do you think painting informed her writing, or vice versa? How large is her painting collection?

In her recent review for The Raven Chronicles, Corrina Wycoff has drawn attention to the color symbolism in RFWO. Her analysis signals a breakthrough in terms of understanding how Crysta’s painting informed her writing. This is an exciting development. And George Stamas has remarked upon Crysta’s storytelling through painting, comparing her in this respect to Charlotte Salomon, the Jewish-German painter who died in the Third Reich’s gas chambers, and who, in a series of frenetically-generated gouaches, painted the events of her short life as they unfolded.

Many of Crysta’s paintings have been lost. She gave them to friends and to those whose portraits she painted. She’d have parted with them at the nearest bus stop, if someone showed real interest. George Stamas, who curates the electronic versions of her art, can’t put a number on the collection. Crysta gifted two paintings to me, including the one that we used for RFWO. So, we had the painting on hand to be photographed, but, more importantly, it depicts her at the “AWOL” stage, when she declared herself a resident poet and refused to report for duty. In “Self-portrait,” Crysta tells the story of how the Green Cammie painting (which we reproduced for the cover for her posthumous Green Cammie chapbook from Floating Bridge) was stolen from her room at the base. George Stamas informs me that  Crysta tried to repaint Green Cammie, but was dissatisfied. At some point, the original canvas was mailed back to her, out of the blue. Clearly that painting was psychologically fraught: for the thief, for the rescuer, and for Crysta herself. Another particularly potent piece was her portrait of the late Seattle poet, Harvey Goldner. When Crysta brought it to the hospital to show him, he said, “You’ve made me into an angel.”

Crysta tried to repaint Green Cammie, but was dissatisfied. At some point, the original canvas was mailed back to her, out of the blue. Clearly that painting was psychologically fraught: for the thief, for the rescuer, and for Crysta herself. Another particularly potent piece was her portrait of the late Seattle poet, Harvey Goldner. When Crysta brought it to the hospital to show him, he said, “You’ve made me into an angel.”

Did Casey ever envision creating a poetry/painting book or paint any of her poems?

She definitely wrote about some of her paintings, but I don’t think that she painted any of her poems. Still, I’d say that some sort of conversation was ongoing, even if no specific mixed-genre book was, to my knowledge, in the works.

Casey is both a narrative and lyric poet, she tells her own story and the stories of others around her—in the hospital, in the military, in the housing communities. What gives her the ability to speak about these different populations so clearly and honestly?

In my introduction to RFWO, I suggest that when she decided not to be a journalist for the Marine Corps, Crysta became a journalist for her fellow Marines, and, later, her fellow vets. Her objectivity helped keep her anchored, as she fought mental illness for her entire life. She kept a journal and wrote emails to George Stamas and others detailing her daily round. She had long struggled for stability, and she pretty much won that battle. As I already mentioned, the military, the VA hospital, and the seedy margins of Belltown (pre-gentrification) often catered to the same clientele. Not all of Crysta’s friends were vets, to be sure, but a number of them were.

Casey seems to have a sense of humor—declaring herself the resident poet for the Marine Corp, for example—and at the same time, she writes about serious subjects: cancer, amputations, death, mental disease, misogyny, war wounds. How does she tackle these two contrasting issues?

She definitely had a sense of humor, including gallows humor. The following short poem about the amputation of some poor guy’s leg was perceived as hilarious by the vets, including perhaps by the amputee himself:

Saw Tom Lent in the Recreation Room.

He said, “When you paint me again

it’ll be easier. They just took off

my other leg.”

There is nothing more serious than a joke, so humor was both barb and antidote. As for the misogyny, I don’t think that she was ever able to find humor in that one, though, come to think of it, she takes Captain Bowman down several notches in “Captain Bowman’s Plastic Spoons.”

What was she like as a person?

What was she like as a person?

She was feisty and upbeat when I met her so long ago in Santa Cruz. Her fighting spirit stayed strong, but it was tempered by wisdom and hard-won forbearance. She was highly intelligent. In terms of her poetry, she was humble but tenacious. She was in love with poetry. She was eccentric. She was generous to her friends and probably saved at least one vet friend from suicide. She shares herself in her poems, so she is with us still. Read her.

—

Deborah Woodard’s most recent poetry collection is Borrowed Tales (Stockport Flats, 2012). She has translated the poetry of the distinguished Italian poet, Amelia Rosselli, most recently in Hospital Series (New Directions, 2015). Her collection No Finis, Triangle Testimonies, 1911, with drawings by John Burgess, is forthcoming from Ravenna Press in 2018.

Letitia Cain received her MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2017. Her poems have appeared in Switched-on Gutenberg, Raven Chronicles and Gravel Literary Journal. In addition to working as the Business Manager for Poetry Northwest, she also works as part of the event staff with Seattle Arts and Lectures. She teaches classes on poetry writing to promote healing and wellness, combining her skills as a physician with poetry.

Images courtesy of George Stamas