Interview // Cathy Park Hong

By Diana Khoi Nguyen | Contributing Writer

Cathy Park Hong‘s first book, Translating Mo’um was published in 2002 by Hanging Loose Press. Her second collection, Dance Dance Revolution, was chosen for the Barnard Women Poets Prize and was published in 2007 by W.W. Norton. Her third book of poems, Engine Empire, was published in Spring 2012 by W.W. Norton. Hong is also the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship and the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship. Her poems have been published in A Public Space, Poetry, Paris Review, Conjunctions, McSweeney’s, APR, Harvard Review, Boston Review, The Nation, and other journals. She is an Associate Professor at Sarah Lawrence College and is regular faculty at the Queens MFA program in Charlotte, North Carolina.

When did you begin to write?

I started to write in high school, but really sporadically, almost as a dare to myself to see if I could do it. I never considered writing as a passion I could pursue—if you told me then I was going to be a poet, I would have laughed.

And who were your earliest writing crushes?

I’m tempted to list only quality, canonized writers like Sylvia Plath, Kafka, and Milan Kundera but then I’d be an outright liar. Besides them, I went through a fantasy/sci-fi phase where I adored Terry Pratchett and Piers Anthony. My first book of poems was at the age of 13, when I bought The Doors’ Jim Morrison’s book of poems. I was a real literary wunderkind.

There’s this really great This American Life episode about this 15 y/o boy who leaves home after narrowing down where he thinks Piers Anthony lives. It’s incredible. Kind of like My Side of the Mountain, except instead of living on turtle soup in a hollowed-out tree trunk, it’s a sci-fi idol.

So tell me what college was like.

I went to Oberlin and I couldn’t think of a better school for me. Probably like most poets, I was a socially awkward recluse in high school and despised its homogeneity and conservatism and craved to escape that experience altogether.

So much to my parent’s dismay who were hoping I’d go to a more name-brand school like Berkeley, I chose Oberlin, which they tried to sell off to their friends as the “Harvard of Ohio.” Oberlin is in a desolate stretch of Lorain County and there’s absolutely nothing to do so students had to entertain themselves by being in bands, becoming vegan activists, and throwing drag parties. It was there that I made the best of friends, became politicized, and believed in making radical art. I discovered poetry. I made horribly pretentious installation art like washing random people’s feet in a chapel with a video projected against the altar. I went to punk shows, lived in dirty co-ops, stopped taking showers and had equally unwashed boyfriends. I discovered Marx, Adorno, Derrida and Spivak. It was all very much a liberal, liberal arts education and I loved every minute of it, even the depressed parts.

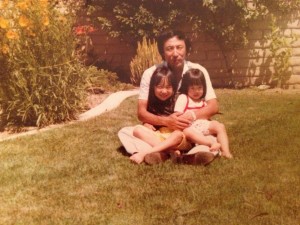

I love it! And wish I could have witnessed some of this installation art and unwashed youths. Do you have any young CPH photos you wouldn’t mind sharing with us?

I really don’t know if you’d want to be subjected to my old art. As far as photos…

When did you know you wanted to be a teacher?

When I was at Oberlin, I had a class with Myung Mi Kim who was brilliant, and it was the first time I fantasized about being a professor and changing the DNA of the way students think, which is what she did with me.

I love Myung Mi! I’ve been dying to be a student of hers. What other jobs have you had besides teaching?

I was a fact-checker, a reporter, an assistant editor for the Village Voice. I also worked at a library resource center, waitressed and worked as a barista which I was terrible at, and worked retail, shilling aromatherapeutic cleansers, which I was also terrible at.

As a young person working on her first book, what I always have to ask is: How did you get your first book published?

I was both lucky and dumb. A couple years after undergrad, I had a bunch of poems that I considered a finished manuscript. I knew nothing about po-biz. I didn’t have any poet friends even and the internet was not the explosion of poetry presses and journals it is today. I had a couple poems published in Hanging Loose journal and decided to send my manuscript to their press. I think I also sent it to Yale Younger or National Poetry Series, and made a decision that if I got my book published, I wouldn’t go to grad school. Months passed and no word. I applied to grad schools, got into Iowa, and on my second day there, I got a phone call from Hanging Loose saying they wanted to publish my book.

Hanging Loose Press is a fantastic press and a lot of amazing writers—like Maggie Nelson, Eula Biss, Wayne Kostenbaum, Kimiko Hahn—got their start there. But I would have done things a little differently. I was so young and still developing as a poet. I would have waited, wrote more, worked on my manuscript until it really felt finished, and sought more advice.

An abundance of riches. That’s amazing! What was grad school like? Did you love it as much as you did your undergrad?

Not exactly. I had a more complicated relationship with Iowa. I had amazing and supportive professors like Mark Levine, Cal Bedient, and Cole Swensen but it was hard to be a poet of color there. You have to understand, I was coming from Oberlin, which is PC to a fault, coming from New York, coming from working at the Village Voice where the paper was obsessed with covering the Diallo shooting and other racial profiling cases. To go from that to Iowa was a culture shock. I remember when I visited, a bunch of guy poets took me to a sports bar and bragged about how awesome and accomplished their year was and discussed Eliot like they were talking football. I was thinking, “What am I getting myself into.”

But the climate changed while I was there. Workshop students of color got together and tried to change the curriculum. I was also part of an experimental poetics and politics group there. Some of the smartest and most talented people I know are poets I met at Iowa. Everyone was so passionate about poetry—I really believed poetry could be revolutionary. So as socially conservative as Iowa was, a corner of it also fostered some crazy, forward-thinking writing. For instance, Action Books and Lana Turner came out of there.

And what did you do after graduating from Iowa?

I returned to New York and resumed trying to make it in journalism and living a very drunk, anxiety-prone 20-something life. Steady paychecks came from fact-checking at magazines like The Source and Spin–I ended up getting fired from Spin for not getting along with this terrible boss whose personality bore a strong resemblance to Tracy Flick’s from Election. I was also reporting, writing local politics articles for the Village Voice. Then I got a Fulbright to go to South Korea which was life-changing. I was there, translating and working as a freelance journalist. I mainly wrote about human rights issues in China and North Korea and met so many fascinating people—North Korean defectors, poets, entitled foreign correspondents, doomsday fundamentalists, undercover NGOs. In my free time, I hung out with this group of noise musicians. The thing about Seoul is that the counterculture scene is quite hidden but because it’s that way, it’s really vibrant and close-knit. And best of all, I met my husband in Seoul.

Oh! So you met your husband, artist and filmmaker, Mores McWreath in Seoul!

Yes. He was also living in New York beforehand. His girlfriend broke up with him and his best friend who was teaching English in Korea for a year convinced him to move to Korea and teach. We met through my sister who was also living there at the time and we fell in love quickly. My parents weren’t too happy about the fact that I went all the way to Korea to meet a white boy from Brooklyn.

God, I love (epic) stories of travelers’ love. If you could talk to a younger Cathy, say, Cathy her mid-20s, what would you tell her?

Be patient and don’t be so hard on yourself. I’m still telling myself that.

Do you have any other advice–especially to young writers who are struggling now?

Maybe because I live in New York or because we’re in the belly of the social-media beast, but I find that younger poets now are savvier than ever, but also more anxious than ever about jumpstarting their poetry career. I have students who are panicked about not being connected enough but this anxiety to connect actually disconnects you from what truly inspires you. So I urge poets to avoid writing poetry that will be liked in this relentless era of likability. Write towards what makes you uncomfortable. Find your vocabulary and music from unexpected places—stand-up, dub, old maps. And try not to calculate your career too much—like moving to a certain city, following trends–because it will lead to derivative work. The best kind of poetry occurs from the strange and convoluted route. Try to get paid to travel like teaching English abroad. Start a magazine or write manifestos not as a career bump but because you want to bust the status quo and you have something to say. And of course, through all of this, write.

A native of California, Diana Khoi Nguyen is working on completing her first manuscript in Lewisburg, PA. She has poems and reviews in or forthcoming in Poetry, Lana Turner, Kenyon Review, West Branch, and elsewhere. www.dianakhoinguyen.com