Interview // “Abject Uncertainty”: A Conversation Between Jeff Alessandrelli & Ashley Yang Thompson

Introduction from Jeff

I first came across Ashley Yang Thompson’s work in her chapbook Sky Mall, collaboratively written with the poet Mikko Harvey. Sky Mall is an absurdist collection of prose poems that features a bunch of different items available from the famed Sky Mall catalog. Sky Mall the chapbook is an amazing little volume. One of my favorite poems in it reads:

White Windows

White windows are my passion.

Instead of glass, you have a solid, white mass.

This way, your children are safe because they won’t be

tempted to jump out of windows when they aren’t loved

back.

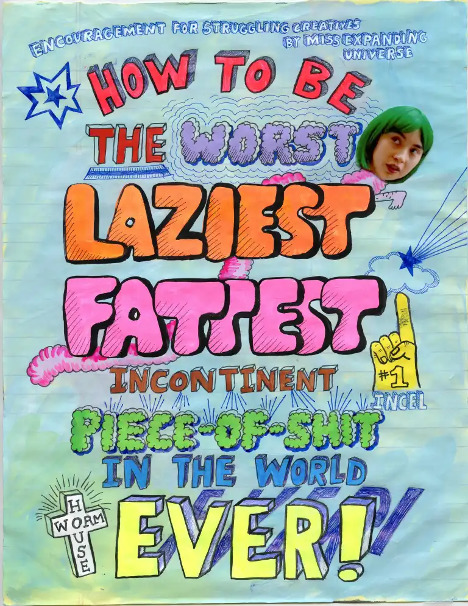

When earlier this year I found out that Ashley was living in Portland, OR, where I also live, and had a new hybrid poetry/art chapbook amazingly titled How To Be The Worst Laziest Fattest Incontinent Piece-of-Shit In The World Ever! Encouragement For Struggling Creatives by Miss Expanding Universe, I knew I wanted to talk with her about it. Touching on influence, reading habits, and normality (or lack thereof), our conversation below was wide ranging, but one touchstone thing I took away from it is how important, in both her life and work, truth (both real and imaginative) is to Yang Thompson. There is only one word and millions and millions of ways of speaking it.

Introduction from Ashley

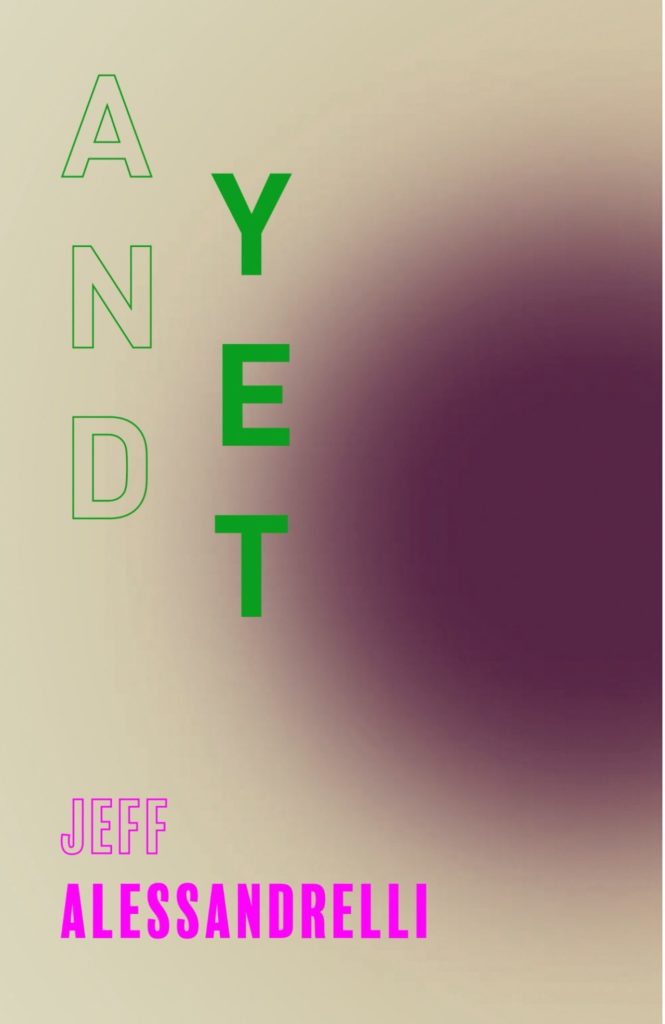

I invited Jeff to be a visiting lecturer at my MFA program this past spring, and beyond satisfying my need to perorate on Fonograf Editions—a local, hybrid press that produces tactile objects which fertilize the mind—Jeff’s stentorian voice expressed a kindred philosophy to my own: a pro-average philosophy of incubation and bibliolatry and neuroticism and a variegated self that is this and that and that and that (in Jeff’s case, skateboarder and poet and essayist and experimenter and director of a book press/record label) in a society that lauds Pulitzer Prizes and monomania. When he told me he had a book coming out about total shyness and prurience and limerence (the story of my heart), I immediately devoured the advanced copy (“containing 1,000 errors”) he gave me, recognizing fragments of my scattered self throughout.

Ashley Yang Thompson: And Yet reads like a commonplace book—nearly every page is littered with repurposed literary inheritances. To me, the protagonist’s relationship to reading is the primary relationship in the book. This is something I relate to, because I believe that when we read we inevitably learn more about ourselves than the author, and that through our creative exegesis of a text (i.e. another person’s brain), we alter and remix it into some new, delectable hybrid fruit.

At one point, the protagonist’s therapist says . . . [some brand of existential failure] has to do with being able to see yourself for who you are without having to rely on anyone else, no Tolstoy or Dostoevsky or the imagination. I’m currently in a Studio Art MFA program and one of my professors (who is also kind of my therapist) has proffered a variation of this sentiment. Do you feel like the compulsion to be derivative is a form of rejecting one’s own thoughts? Is quoting a way of procuring permission to believe what we believe, because we are simply incapable of giving ourselves permission to exist as we are?

Is it possible to read too much?

One of the last things my father told me before he died was, there are things you can’t learn from books . . .

Jeff Alessandrelli: And Yet definitely uses dozens upon dozens of sources and reference points . . . it revels in citation, actively so. But I don’t know if I think of that as a “compulsion to be derivative,” exactly. One of my favorite writers is Eliot Weinberger and what I love about his work is how he draws out, via a wealth of different sources, many obscure or unknown, the illusory conception of selfhood. Weinberger writes about himself on occasion and he regularly uses “I,” but his essays (he writes poems too, but is better known as an essayist) typically are devoted to a compendium of revelatory facts or anecdotes that build to some larger whole. I’ve always been interested in history—as an undergrad I minored in it—and at the end of the day I consider myself as much a reader as a writer, probably more so. I honestly don’t think it’s possible to read too much. Or maybe it can be, but I personally view reading–at least from an actual physical book—as a kind of meditation of sorts. (I know that is aggressively cheesy, but I 88.6% believe it.) It centers me, or can center me. I do think there are millions of things that can’t be learned from books, but at the same time I think those things will eventually be learned by a person whether they like it or not. No matter who or where you are, life is always going to interrupt and intrude and insist on its own reality. I don’t think reading is ever going to have any type of counter to that.

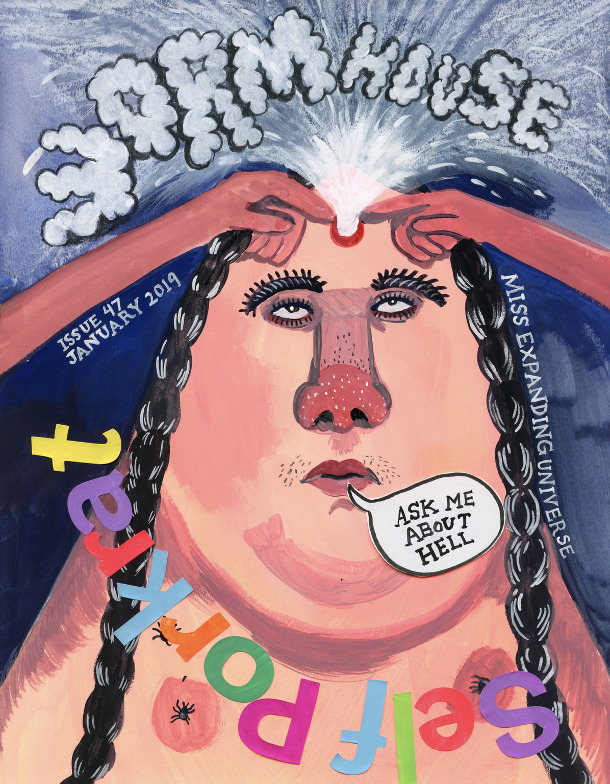

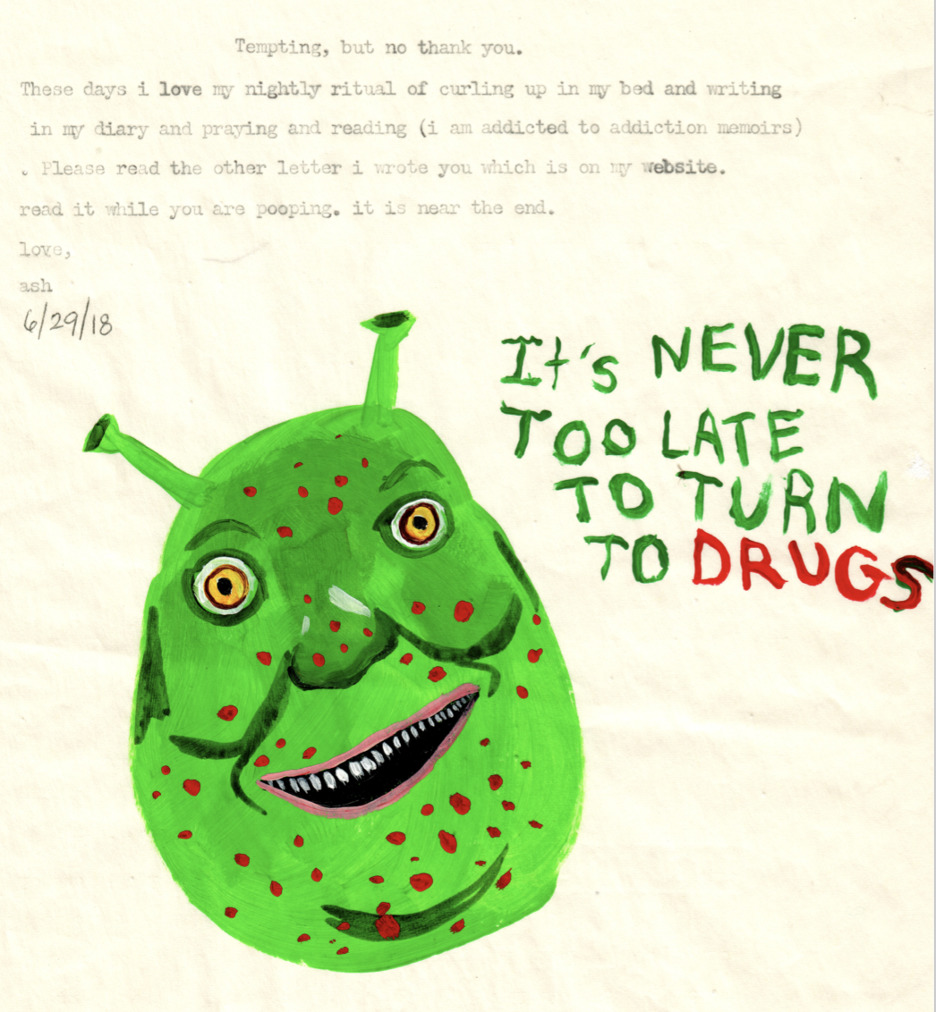

What do you think? You’re a visual artist as well as a writer and in your own recent book How To Be The Worst Laziest Fattest Incontinent Piece-of-Shit In The World Ever! Encouragement For Struggling Creatives by Miss Expanding Universe(HTBTWLFIP-O-SITWE!) the onus definitely seems to be on where visual and textual expression meet in the middle—or refuse to. All the poems in the book are garlanded by visual art works of your own creation and it’s a big book . . . almost the size of one of those old issues of Rolling Stone. The overall artifact seems designed to overwhelm the reader/viewer, at least to a certain extent. And unlike in And Yet, the “I” contained within the poems seems to have more solidity—she’s a person intent on self-understanding by way of sarcasm and self-revulsion. When I see the letter “I” in a poem I typically don’t equate it with the author—but I know I’m in the minority there. How interested or disinterested are you in autobiographical art? Does it bother you when people take what’s on the page/on canvas to be directly related to your own living and breathing (i.e. non-artistic) self? Or does life meld with art in forever-intertwined ways?

Ashley: I don’t think a person can read too much. I read because I don’t know anything, but—lucky me!—I have all of literature (an archive of stuff made out of the human spirit) as my inheritance. By reading I uncover my native tongue, and by native I mean the rhythm and pulse of what is most natural to me, which is writing.

Very few people read poetry, and even fewer people read totally obscure scatalogically inclined poets with no social media or external imprimatur, so whether or not my amoeba readership regards my work as autobiography or autofiction does not weigh heavily on my consciousness. Why is And Yet being marketed as speculative fiction versus autofiction?

I say the real folly is not the reader who equates my work with my life (to whom I say, a snakeskin is not a snake), but the shame itself. So what if it’s true that I eat meat sticks on the toilet because the toilet happens to be the most comfortable place to sit in my 300 foot studio apartment? So what if I have a very unsexy eating disorder, or if my thoughts hum with the hackneyed language that cringy crushes induce? Embarrassment excites me because it carries the tag of oppression. Somebody taught me that I should feel ashamed, and through numerous positive exorcisms (a sobriquet for my creative practice) it might be possible to unlearn these lessons.

The important thing is that the work conveys felt truth.

And Yet includes multiple sentences highlighted by the protagonist and by previous owners of other books. I love annotations because they are like a fast track into another person’s mind, or like being a tourist in an anterior iteration of one’s own mind. I also feel like a good reader shapes the book they’re reading, unlocking interpretations and previously unthought of meanings. By altering the context of texts, And Yet is a work of creative reading as well as creative writing, and also a literary collage and a gateway drug into other authors. Do you see your work in the book that way?

Jeff: The importance of felt truth . . . agreed. But I wonder where imagination and the imaginative factors in or can factor in. Is felt truth more important to you than unfettered, innovative wordplay and language and imagery and all of it? One of my favorite writers is the French Surrealist poet Robert Desnos. His biography doesn’t show up very often in his work, at least not directly. But his relentless imagination always does and that’s definitely why I relish his work as much as I do. The way he thinks on the page is the way I aspire to think on the page and, for me at least, who he was as a person doesn’t factor in much. I guess I’m curious where the balance is between the (starkly) actual and (purely) fictional for you. I gravitate towards the make believe. What about you?

Which brings me to the marketing of And Yet. It’s being couched as speculative fiction for a couple of different reasons. The first is that I tend to view selfhood as inherently speculative, and from one year to the next (or one moment to the next) we’re very different people. The protagonist of And Yet wrestles against this fact throughout the book, and it seemed fitting to thus honor that endless, oftentimes tortured speculation with a speculative fiction designation. Speculative fiction is, I know, oftentimes far more ethereal and otherworldly—i.e. what if there were no city streets in Portland and no cars and everyone lived in orange-colored trees. But I guess I liked the subtlety of simply calling a book that contends with selfhood in the “real world” to yet be a work of speculative fiction.

As for autofiction—I realize it reads like autofiction to a degree. I know people will likely read it as autofiction. The fact is, though, that nearly every character in the book is either fictional or based on a composite (in which case names and most identifying characteristics have been changed). The nameless protagonist definitely shares some of my own life story, but I’m also really hard on him. His central emotions are uncertainty, desire and shame. I certainly deal with my fair share of those emotions, but I’m not defined by them the way the narrator of And Yet is. I exist in the world in a way that he doesn’t. And writing this book I grasped my extreme limitations as a fiction writer. I can’t really create characters. I’m not great at scene or plot. I am good at telegraphing bald emotion, though, and sometimes that’s enough.

That all being said—writing about genre saps every ounce of energy from my eyeballs. Books are books. And Yet is a long prose poem or a braided essay or an experimental novel or a literary collage. (And yes, I definitely do see my work as an assemblage of other texts. Perhaps the only thing that makes it original is its open refusal to be so.) All of those things and none of them. Since it features so many illustrations, would you be annoyed if someone called HTBTWLFIP-O-SITWE! a comic book? A short, elliptical graphic novel? And if writing is what’s most natural to you does it rankle you that you’re also a first-rate painter? And how do you react to phrases like Renaissance (wo)man? Is an abundance of divergent talent in multiple mediums both blessing and curse?

Ashley: Felt truth isn’t necessarily contrasted with imaginative fabrication and phonetic realms. The first time I remember feeling the pulse of poetry, I had no idea what was going on in a literal sense. I was reading the surrealist poem “Sunflower” by Dean Young and the odd correspondence of sonorous stanzas resonated with some interior frequency that flushed my nerves with a physiological charge. The magic of poetry and art (btw I use the words art, writing, and violent diarrhea interchangeably) is that I can enjoy it before I understand it; I just let the words wash over me like a dream. And as time passes and life chisels and burns and shocks me out of neutrality, new significances unfold and the seeds of certain words and images blossom, unraveling some kind of intimate code.

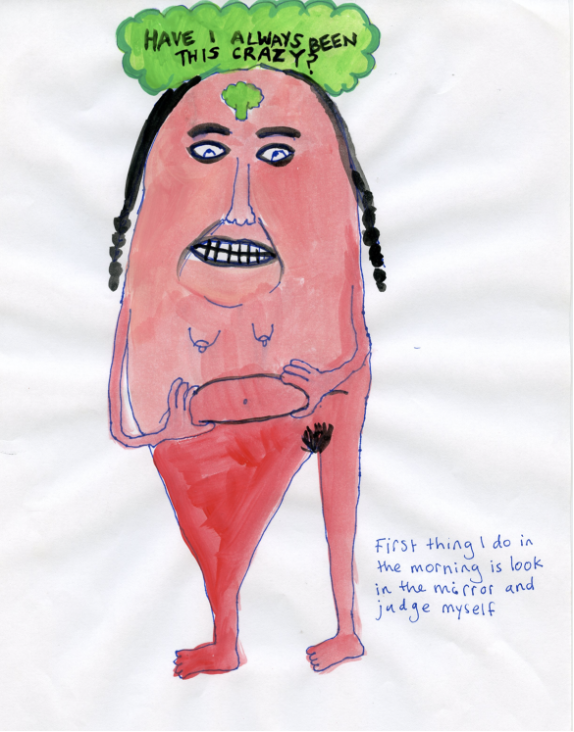

Life is surreal and perception is unreliable. Every thought is an act of the imagination. We go around thinking that what we see is reality, but we are actually just seeing our reality, which is tainted by our uniqueness as a species and as individuals in a certain time and place. What I am trying to capture is the reality of distortion. Like the protagonist in And Yet, the central worm/girl in HTBTWLFIP-O-SITWE! is very hard on herself. She looks in the mirror and her face is a bad acid trip—benign pimples become cystic volcanoes and her body inflates to unacceptable ratios (unacceptable at least to the little chauvinist pigs that have colonized her brain). Her mind is drowning in a tsunami of fuck-ups and regrets. No matter ho-w much she accomplishes, she feels as though she has accomplished nothing, has no career to speak of, and is therefore of no value.

HTBTWLFIP-O-SITWE! leans into this state of abjection: what if worm/girl actually looked like her worst nightmare of herself? The Western argument of beauty is archaic, arbitrary, and repulsively myopic. What is ugly in this century will be beautiful in another. Abjection dissolves boundaries by refusing to deny someone their beauty just because they are wrinkled or bald or too short or too fat. Or that their shirt is stained with the grease of a thousand microwavable pizzas. In the abject universe of my book, teenagers are rubbing butter into their pores in hopes of having their face ornamented with acne by Prom Night and beauty is learning to love your picture of Dorian Gray.

Worm/girl and And Yet’s Everyman are (at times) disembodied nerds festering in incessant self-reflection. I would say that both books are portraits of overthinking, which is usually a pejorative term; it is seen as a purgatorial state that the emotionally stunted subject must overcome in order to be an actual human being. Artists and writers have a tendency to cut through the intellect towards some kind of purity of expression. But the system they’ve devised to overcome the intellectual process is itself an intellectual process. Is overthinking a creative block or is it a generative part of creating?

As for painting—it is a curse that I’m a “first-rate” painter. Almost everyone who has seen my beautiful, meticulously rendered oil paintings addressing “timely” topics is disappointed to encounter scrofulous, scatological drawings on notebook paper. In 2016, I decided to unlearn how to paint. It was time to move on . . . canvas had nothing to say to me anymore. Now all I paint is worms (and only on the shittiest paper) and wormlike things. I am drawn to the worm as an avatar for the self because it is name-shorn, neither boy nor girl, neither Chinese nor white nor 1% indigenous. I want to portray something that has no identity, so that everyone can identify with it. This goes back to the theme of abjection. Abjection disrupts meaning, identity, positions, systems, order, rules, all of it. Worms are unwitting defenders of ambiguity. And my art is invested in exploring that notion.

Jeff: I suppose every artist is trying to capture the reality of distortion in their own idiosyncratic way, right? I guess the danger there is that said reality really can be fundamentally distorted . . . by social media, by rejection, by success, by criticism, by adulation, by indifference. What’s fucked up to one reader is mild to another. Self-acceptance is no doubt the most important kind, but lord knows it’s hard to achieve. And overthinking is surely endemic to most artists, who by default have to be self-involved. Even if their artwork is anti-biographical in every possible way, they nevertheless have to think (and overthink) about how they are going to create the work, spread the word about the work, promote the work, possibly sell the work, etc., etc. If you have a good publicist maybe some of those responsibilities are mitigated, but ultimately I think most artists want to be in control. They want recognition and acceptance and fame and money and security and even power, although that last one might be a bit hard to swallow for certain folks. But I think it’s true. As to whether overthinking is generative or creative stultifying, I think it depends on the artist. Both immediacy and contemplation have their place in my opinion.

One of the interesting frames for the protagonist of And Yet is his abject uncertainty within every single situation. Even when he is home alone he is uncertain. This might ring untrue to some people, but uncertainty is the predominant overhang of all sentient life. Stockbrokers are uncertain. Realtors and data analysts are uncertain. Is there an afterlife? Is there a God? When and how will you die? You won’t know until you know (irrevocably) and up until that point—uncertainty. If worms are unwitting defenders of ambiguity I think life itself, in all its forms, is a thoroughly ambiguous predicament. No one knows, truly knows. You can celebrate or lament that fact, but it’s there regardless.

Final question—we’ve gone all over the place in this interview, which seems fitting based on HTBTWLFIP-O-SITWE! and And Yet’s wildly variegated forms and themes/topics. So what’s the most “normal” fact about you, either personally or creatively? For me it’s probably that I’m very routine oriented. I go to bed at a certain time, get up at a certain time, eat breakfast and lunch at a certain time, walk my dog at a certain time, etc., etc. I like the mundanity of routine, which provides me with stability and structure. I’m like a 76-year-old retired person, essentially. What’s your own normality framework?

Ashley: Everything about me is normal.

The weirdness comes from how I choose to express my normalcy.

Retrofitting the normal is essentially what art is (my favorite example being Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined teacup). I could write a whole book about this (stay tuned) called Everything about me is normal but I’ll just say that I, too, am a septuagenarian in disguise. Actually, my nearly nonagenarian Popo (grandma) goes to bed later than I do. I exercise religiously, i.e. I am overexposed to Lycra while righteously fulfilling my thirst for the hard labor of Russian serfs, I consume reasonable quantities of salutary fiber at regular intervals, I sleep the recommended 8 hours a day, et cetera. I am a slave to patterns that genuflect to the cult of Heath and Positivity (incessant self-optimization), which really puts a damper on things like pleasure (literal and metaphorical dessert) and spontaneity and surprise . . . all for the sake of comfort and consistency and the security of bogus numbers. Substituting routine for life is one of the most normal recipes for human existence.

Ralph Waldo Emerson—my spiritual grandpa—would want me to lose myself, to not know what I’m doing, to cut loose and let my soul travel abroad . . . which reminds me of my favorite poem, “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop. The art of losing isn’t hard to master. I hope to break long enduring habits. I hope to lose every identity I attach myself to, I hope to estrange myself from the systems I was born under, I hope to celebrate the loss of youth & its cultural capital of smooth skin, I hope to wriggle into the fertile void that materializes when we lose someone we love. In art I have the courage to do what I can’t do in life—I allow these anti-cultural positions to bloom, but in my day-to-day I find myself squeezing into the straight jacket of normalcy. And yet . . .

—

Ashley Yang Thompson aka Miss Expanding Universe aka “Trash” is the author of the underground self-help cult-classic How to be the worst laziest fattest most incontinent piece-of-shit in the world EVER, published by Bateau Press. She is the co-slutmonster of WORM SLUT, a Portland-based weekly zine that celebrates mesh crop tops, the Right To Be Lazy, burritos, spending beyond your means and the metonymy of sucking.

Jeff Alessandrelli is most recently the author of the poetry collection Fur Not Light (2019), which The Kenyon Review called an “example of radical humility . . . its poems enact a quiet but persistent empathy in the world of creative writing.” Entitled Nothing of the Month Club, an expanded version of Fur Not Light was released in the United Kingdom in 2021. In addition to his writing Alessandrelli also directs the nonprofit book press/record label Fonograf Editions. https://jeffalessandrelli.net/