How to Listen to the Magic

by Jose Hernandez Diaz | Contributing Writer

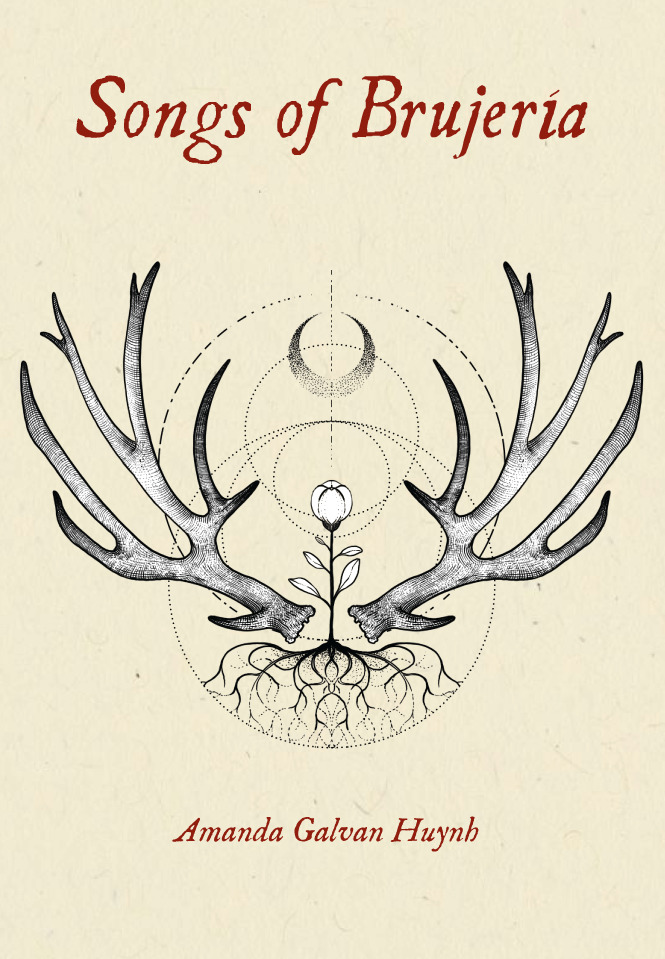

Songs of Brujería

Amanda Galvan Huynh

Big Lucks Books, 2019

Songs of Brujería opens with “Before My Mother Was Born,” a poem in which Galvan Huynh describes the disappearance of her grandfather: “before she was born / her dad died in an / accident except it / wasn’t an accident . . .” We are immediately drawn into the poem by the mystery surrounding her grandfather’s disappearance. What happened to her abuelo? How did he disappear? Later, Galvan Huynh relays more information: “their dad was / shot in the fields / while working maybe / over drugs or / something . . .” The tension in the poem rises. Why was her abuelo shot? Who did this to him? Then we find out the horrific details: “they / shot him then they / turned his tractor on / let it run over his / body . . .” This poem immediately announces that, in Galvan Huynh’s Songs of Brujeria, we are in a tough and vulnerable world. The poem ends the poem by explaining lineage, how the fields where her father was shot persist in her mother’s everyday workplace: “there are / nights she dreams / those gashes feel / like the fields she / works in every day.” Unable to escape the harsh realities of the fields that took her father, Galvan Huynh’s mother and family nonetheless carry on, with no option but survival.

In another poem, the speaker tells of a family’s itinerant lifestyle, working from one harvested field to the next. In “Her Family Moves,” Galvan Huynh depicts a scene of an average moving day, where for practical reasons, there isn’t room for precious childhood belongings: “It doesn’t know / that there’s no room / for her First Communion dress / or that she hides her white / ribbon bow in her pocket.” Throughout Songs of Brujeria, we see people who have to grow up quickly and learn to put family ahead of personal needs. Later, the girl watches her mother loading the car for the move: “She piles / crates into the trunk, replaces / her doll with a bag of pans.” Your heart breaks for this child who must leave a beloved doll behind, because of the mundane necessity of the pans.

In “First Time She Interrupted Mamá,” we encounter another striking moment:

The first time she interrupted Mamá

she was talking with her sisters

in the kitchen. Arroz simmered

in its tomato juice; the blood smeared

between her legs was brighter.

The speaker goes on to describe her initial reaction to the discovery of the menstrual blood as a fear of both death and of getting in trouble with her mother: “At thirteen, / she thought I’m dying. She thought I will die // if Mamá sees these stains, blooming in her shorts.” When she eventually does muster the courage to tell her mother about her period, she isn’t necessarily scolded, but is instead questioned : “Did your brothers touch you there? / She shook her head. Mamá nodded, closed // the cabinet.” The speaker learns to never interrupt Mamá again, not just because of punishment, but utter shame: “Put that in your chones. Mamá / shut the door behind her, the kitchen’s noise / rose, and she never interrupted her again.” Viscerally, the speaker in the poem realizes that although she had every right to tell her mother about her period, because she is her daughter and because she was never educated about it, it is still better to keep quiet about personal things, because nothing is worse than shame in front of her mother’s hard eyes.

In the title piece of the collection, “The Songs of Brujería,” we get to know of the connection the speaker has with community. The chapbook may seem occasionally bleak up to this point, but the title poem chooses to celebrate her Mexican-American/Latinx culture. It begins by seamlessly mixing Spanish with English:

La Luna would be the brightest on Saturday nights,

for a quince, a wedding, or some other reason

to celebrate—to fill a dance hall:

tías refilling plate with barbeque

and gossip. Beer bottles humming

around mouths.

Warmly, we are welcomed to Galvan Huynh’s neighborhood, or barrio, where quinceañeras and weddings (or any reason to party, really) are celebrated with beer, chisme, and general alegría. The speaker’s community is consumed with family and love of life; much like the rhythmic cumbia that plays loudly in the background. Importantly, the speaker knows the origins of this alegría and familial pride: it is the women of the family who drive the Latinx community: “These were the songs / of brujería and this was where the women / in my family practiced.” Galvan Huynh speaks not necessarily of a brujería as evil, but of the hope and light in this spirit. It is the pulse of the neighborhood. At the end of the poem, the speaker further elaborates about a feminine guidance toward this magic, or brujería: “She would teach me how to listen to the magic / found in those nights—as if all I had to do / was press my ear to my pulse—to find my way home.” For Galvan Huynh, this charm and love of life pulses in her veins: it is her birthright.

Toward the end of the collection, in “Verses,” we find another moving moment between an immigrant mother, her first-generation daughter, and the acquisition of language. Many first-generation Latinx folks, myself included, have gone through a similar experience: when a parent asks you how to spell, pronounce, or translate a word: “I’m ten and she calls me / to check her spelling—How do you spell appreciate? / She pronounces the word, ah-pre-key-ate.” The speaker goes on to explain the complexity of language to immigrant communities: “I correct her, but my mouth carries the hesitation / of her tongue, of her fragmented education, the belief / that intelligence is hereditary.” Not only does the speaker have to deal with the pain of having to correct her mother’s English at the age of ten, but she is also left wondering if she too will struggle with words based on genetics or her lack of privilege. After reading this poignant collection, we can clearly see Galvan Huynh’s mastery of not only language, but also her respect for the art of poetry and her deep love of familía.

—

Jose Hernandez Diaz is the author of the chapbook of prose poems, The Fire Eater (Texas Review Press, 2020). He has been awarded a fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts, and he lives in southern California.