How Do the Words Dream Together?

by Randall Potts | Contributing Writer

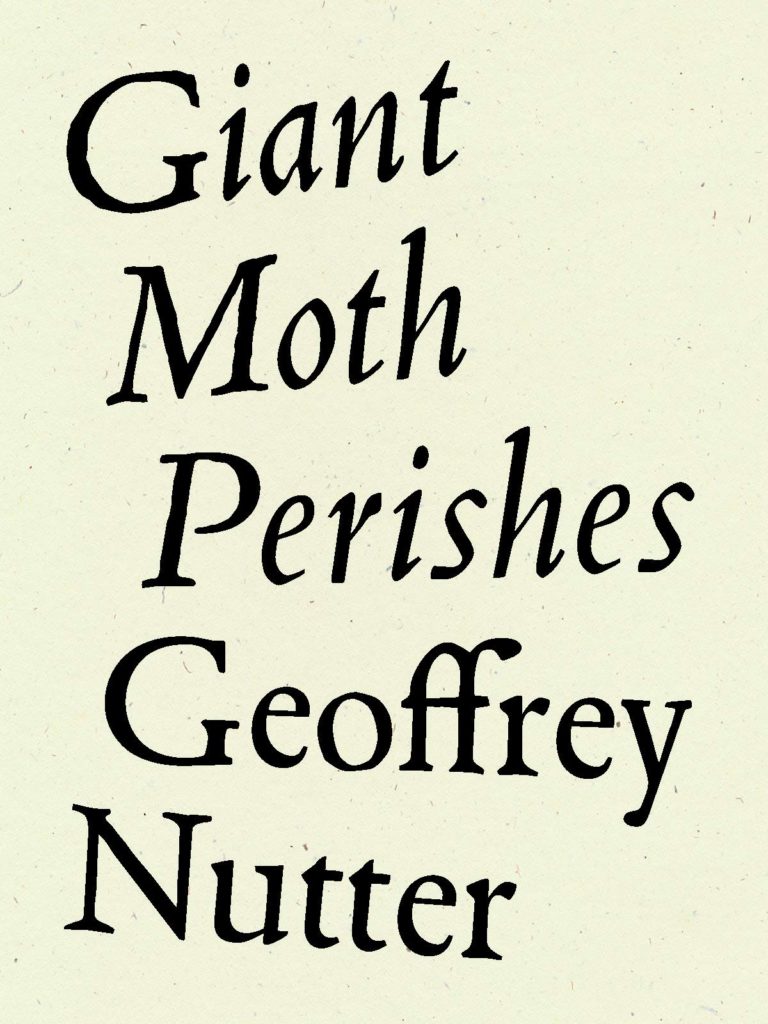

Giant Moth Perishes

Geoffrey Nutter

Wave Books, 2021

Geoffrey Nutter’s sixth collection, Giant Moth Perishes, begins with the aptly titled poem “The Faerie Queen“: “I sleep while reading, and sleep / while writing a poem, and I sleep / while I’m talking.” Sleep and all the hypnogogic states between sleeping and waking are a recurring theme in this book, and it’s instructive that the first poem should reference Edmund Spenser’s epic allegorical masterpiece. Nutter immerses us in a world that is at once recognizable and yet radically different from our everyday reality.

As Albert Einstein wrote, “If light is simultaneously both wave and particle, then we no longer know what is,” so too Nutter suggests the real is far stranger and malleable than we habitually assume. As the first poem concludes: “Life, according to the Dictionary / of the Underworld, is called ‘the book’; / but it is also called ‘from now on.’”

On this book’s journey, Nutter offers the reader a gentle friendship, but not self-disclosure. Instead, he creates a fantastical and encyclopedic reality of daydreams, lists, revelations, jokes, paradoxes, and pseudo-narratives that explicitly include the reader as “we” or “you,” in an act of generosity that emotionally grounds this visionary poetics.

He is determined to both delight and confound us, while his enthusiasm and genuine love of language carry us beyond the limitation of our senses and our transactional reality. At its core, these poems acknowledge the solitude of existence, the need for solace, and our desire for companionship. While the virtuosity of the imagery might recall early John Ashbery, the speaker is more intimate and humane, something so rare in poetry that it feels more akin to a film, like Jonathan Miller’s 1966 version of “Alice in Wonderland” for the BBC.

This intimacy is often expressed as humor, which animates the poems and draws the reader ever closer to the speaker. Nutter’s humor is never at the expense of the reader, but more like a jest exchanged between friends. He is keen to lure us down rabbit holes into wonderlands of enticing paradoxes. But contrary to Lewis Carroll’s wonderland, the reader is included with the speaker as a companion. In “Tata Conglomerate,” Nutter deploys a Dadaist repetition of the word “tata” (which conventionally might mean either “goodbye” or slang for “breasts”), until it is meaningless, because through the frequency of its usage it comes to mean so many things. In “Study of Blue,” he begins “Think of a poem, concise— / concise to the point of obscurity” and then deconstructs obscurity, objectivity, and even colors, until we are finally left with “blue atoms.”

“A Yellow Vase in Its Environs” takes a different tack. With a nod to Wallace Stevens in the title, Nutter disassembles subjectivity, concluding: “O what name / or title suits your greatness, / Aldiborontiphoscophornio?” The name seems too absurd to be real, but it actually refers to a bellicose character in an obscure play by Henry Carey from 1734. Notably, the play was seen as both nonsense and a sarcastic discourse on Robert Walpole and Queen Caroline and/or the conventions of opera. This seemingly imaginary name that is in fact real—though the reference is obscure—is a prime example of how Nutter aims to transform our rigid concepts of language, reality, and the self, while creating a sense of intimacy like two friends joined in laughter.

The transformative nature of song is also essential to appreciating these poems. Sometimes musicality (which abounds in these poems) is so beautiful that it is an end in itself, rather than a means to an idea or revelation: “We shortened ropes by wetting them, / undid saffron knots for rough brocade, / and memorized The Sceptical Chymist.” Yet, in the same poem, “Mysterious Travelers,” Nutter cannot completely resist meaning, ending with the lines “How do the words dream together? / How to make you live inside their dream?”

As Nutter said in an interview with Emily Kaufman, “We move through language toward discovery—not the other way around.” So, in “Juan Fernández Firecrown,” we are told, “our virginity is not lost (we are transforming / out of it and back again) and time will not obtain.” Or in “Clocks That Strike Only at Sunset,” we are told, “‘. . . I accept all, / forgive all; you can pretend, and I can / pretend along with you . . . I will be one among them, / and you will feel glad to be among the living.'”

There is a Whitmanesque quality of wonder and inclusivity in these poems, but also a directive. The very last line in this book, following the acknowledgements, is a fragmentary quote from Whitman’s poem “Starting From Paumanok,” which is even more revealing in context:

And while I paus’d it came to me that what he really sang for was

not there only,

Nor for his mate nor himself only, nor all sent back by the echoes,

But subtle, clandestine, away beyond,

A charge transmitted and gift occult for those being born [Italics mine]

The song of this book exists not only for us (the speaker and the reader), but extends “away beyond” as a “gift occult for those being born,” which is a curious, metaphysical use of song. In “A Story about Helicopters,” Nutter writes, “The mirror of the heart reflects our waking dreams, / and the dreams that haven’t yet wakened you.” Perhaps this is the paradoxical purpose (or one purpose) behind this book: to give life to dreams that awaken us to the extravagant universe of being and imagining. And yet, there is always a counterforce as in the title poem, “Giant Moth Perishes,” which concludes:

. . . And birds

are in the vines, among the praises,

calling down among the nightshades

where the giant moth perishes.

And she brushes the enormous infrastructure

with her wings.

For many poets, this might be all or at least enough, yet here there is so much more. The book concludes not with the title poem and its dramatic denouement, but with “The Gathering Sea,” a collection of 66 free-form haiku, each like a wave that rises, crests, touches the shoreline, and then recedes into the next wave. This is the final compendium of wonders, the “gift occult,” and there is no way convey their effervescent momentary surges, except to quote a few:

In the dry cleaner’s window—

Spindles of red and yellow thread

While the snow falls.

Lepidopterist dozing in the woods:

A giant blue moth

Opens and closes its wings on your shoulder.

Folded note from a stranger:

“Destroy an apple

With your mind.”

Under the sun:

A basket of nails;

An acre of sunflowers.

Then, in the final haiku, something remarkable occurs:

At sunset

A door

And the gathering sea.

We are left with the sea as birth, death, and rebirth, the poem and the book refusing closure and instead insisting upon a metaphysical occurrence. In this last haiku, the generous, delightful, mischievous speaker is gone, perhaps through the “door” that leads anywhere, and the reader is gone as well. In the end, we must accept the “gathering sea,” and admire a sunset over landscape in a world that no longer includes us.

—

Randall Potts is author of Trickster (University of Iowa Press, 2014), Collision Center (O Books, 1994), and a chapbook Recant (A Revision) (Leave Books, 1994). They live in Bellingham WA.