Holiday with the Hangman: Reading Frederick Seidel’s “Barbados”

By Jay Aquinas Thompson | Contributing Editor

First, dear reader, take the seven-minute trip with me:

—And now, because no industrious poem-bootlegger has shared the poem’s complete text online, you’ll have to settle for my reasonably extended quotations in discussing one of the most ghastly, self-damning, and explosively beautiful poems I’ve ever read: a rich white man’s nightmare of the suffering underneath a colonist’s paradise.

The poem begins by establishing—that is, dis-establishing—its speaker.

Literally the most expensive hotel in the world

Is the smell of rain about to fall.

It does the opposite, a grove of lemon trees.

I isn’t anything.

It is the hooks of rain

Hovering with their sweets inches above the ground.

I is the spiders marching through the air.

The lines dangle the bait

The ground will bite.

Your wife is as white as vinegar, pure aristo privilege.

The excellent smell of rain before it falls overpowers

The last aristocrats on earth before the asteroid.

I sense your disdain, darling.

I share it.

The “I,” along with other final aristocrats, dissolves in its exquisite sensation—and I can’t think of opening lines more exquisite than those first two—over a living natural world, before its final obliteration.

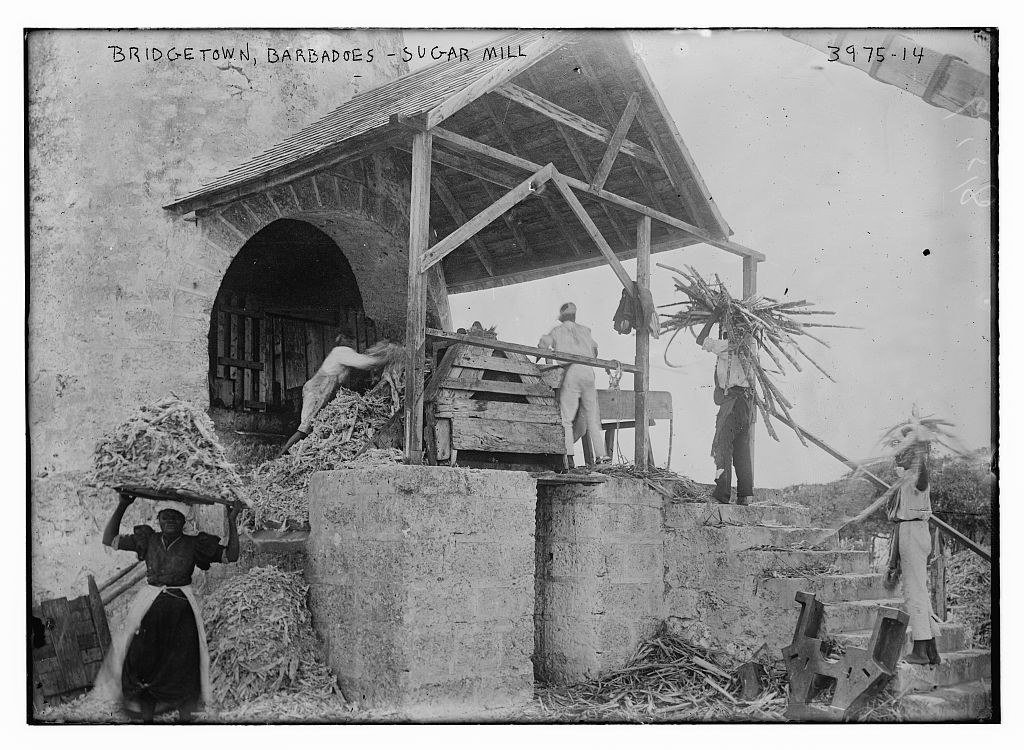

And what could come next? In the meantime, what vision is delivered to this “I”? A vision that’s not much removed from the economic history of the real-life Barbados. In the machinery of a sugar mill set on a lunar hilltop, an African slave’s trapped “black arm” is ground into “brown sugar”—“the machine inside the windmill isn’t vegetarian”—and white hunters come to a village to shoot its “friendly hippos dead.” Grinding, drowning, clitorectomy, being hacked to pieces; cinemas, drink orders, white roads blazing in sunlight, a crocodile president striving “to secure those international loans”: the extremity of the contrast is no great distance from the extremity of actual lived misery in almost everywhere Europeans once colonized.

And what could come next? In the meantime, what vision is delivered to this “I”? A vision that’s not much removed from the economic history of the real-life Barbados. In the machinery of a sugar mill set on a lunar hilltop, an African slave’s trapped “black arm” is ground into “brown sugar”—“the machine inside the windmill isn’t vegetarian”—and white hunters come to a village to shoot its “friendly hippos dead.” Grinding, drowning, clitorectomy, being hacked to pieces; cinemas, drink orders, white roads blazing in sunlight, a crocodile president striving “to secure those international loans”: the extremity of the contrast is no great distance from the extremity of actual lived misery in almost everywhere Europeans once colonized.

The former president completely loses it and screams from the stage

That someone fucking stole his fucking phone.

The audience of party faithful is terrified and giggles.

This was their man who brought the crime right down

By executing everyone.

The poem’s speaker, this dematerialized “I,” condemns nothing, and has not come to set anything right. There’s no divine justice in “Barbados”: the only transcendent entity keeping a moral score of the poem’s horror is the poem itself, and how it seems to overmaster its speaker.

Suddenly the field is filled with souls.

The field of sugarcane is filled with hippopotamus cane toads.

They always complained

Our xylophones were too loud.

The Crocodile King is dead.

The world has no end.

There seems to me to be something morally crucial in the mysterious final two lines of this passage (from what strange poetic ether could such lines have possibly been transmitted?). Seidel the poet is not just creating a spectacle to appall the reader; the poet, too, is being violently seized by the poem’s vision, receiving its transmission whether or not he’s willing. This is the quality that separates the poem from a mere horror-litany, from something Seidel is subjecting us to.

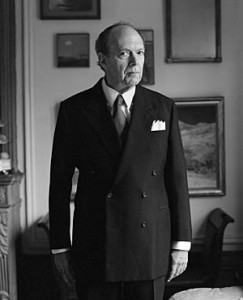

And speaking of being subjected to Seidel: the easy pride Seidel elsewhere takes in his own poetic transgressions is matched only by the easy hatred many of his readers feel for the same. Look around online and you’ll find lots of readers disgusted by his poems’ many Ducatis and fur-trimmed coats, his honey-dripping credit cards and young women on all fours, his rich little East Coast destinations, his offhand lines like “a naked woman my age is just a total nightmare.” You’ll find other readers—many liberal white men—believing they take a heroic stand against some imagined “politically correct” foe by championing the poems precisely for their surface provocations, their casual affluence-signifiers and equally casual grotesquerie.

And speaking of being subjected to Seidel: the easy pride Seidel elsewhere takes in his own poetic transgressions is matched only by the easy hatred many of his readers feel for the same. Look around online and you’ll find lots of readers disgusted by his poems’ many Ducatis and fur-trimmed coats, his honey-dripping credit cards and young women on all fours, his rich little East Coast destinations, his offhand lines like “a naked woman my age is just a total nightmare.” You’ll find other readers—many liberal white men—believing they take a heroic stand against some imagined “politically correct” foe by championing the poems precisely for their surface provocations, their casual affluence-signifiers and equally casual grotesquerie.

So what makes “Barbados” different from the many Seidel poems whose horror hides little depth? In “Barbados,” affluence and apocalypse, the comforts of the wealthy and the reproach of the invisible, are brought unbearably close.

These epileptic foaming fits dehydrate one,

But justify the cost of a honeymoon.

The Caribbean is room-temperature,

Rippling over sand as rich as cream.

The beach chair has the thighs of a convertible with the top down.

You wave a paddle and the boy

Runs to take your order.

Many things are still done barefoot.

And, beyond these excruciating transpositions, “Barbados” does things: just as the speaker seems possessed by the poem’s awful vision, the poem likewise makes my stomach involuntarily crawl and my head spin and my adrenal glands flood me with cortisol. In his other poems, Seidel’s elephantine metrical and formal moves are often used for simple shock or cold punchlines (“My dynamite penis / Is totally into Venus”; “The richest man in Delaware / Died steeplechasing, debonair”). But in “Barbados,” Seidel’s ding-dong devices create huge effects. Feel what happens with metrical expectation in this passage near the end of the poem.

Into the coconut grove they go. Into the coconut grove they go.

The car in the parking lot is theirs. The car in the parking lot is theirs.

The groves of lemon trees give light. Ooga-booga!

The hotel sheds light. Ooga-booga!

The long pink-shell sky of meaning wanted it to be, but really,

The precious thing is that they voted. Ooga-booga!

If you made it all the way through the recording above, maybe you’ll agree with me that Seidel is an over-refined reader of his own work. His meticulous and subdued manner stands in tension with—rather than getting caught up in—the declamatory energy, brutal humor, and horror of the text. His reading’s subtlety has its own awful effects on the listener, but with a poem like “Barbados,” I miss the language’s full rhetorical might. The vivid contempt and prophetic power of “Barbados” bring home something only implicit in most of his poems: that the very emblems of wealth Seidel enjoys are extracted through terrible violence, and point toward a future annihilation of his “tribe” (meaning the similarly affluent, meaning many of us Americans) and perhaps, of everything else. If you don’t believe me that Seidel senses doom—his and ours—, here’s how the poem ends:

If you made it all the way through the recording above, maybe you’ll agree with me that Seidel is an over-refined reader of his own work. His meticulous and subdued manner stands in tension with—rather than getting caught up in—the declamatory energy, brutal humor, and horror of the text. His reading’s subtlety has its own awful effects on the listener, but with a poem like “Barbados,” I miss the language’s full rhetorical might. The vivid contempt and prophetic power of “Barbados” bring home something only implicit in most of his poems: that the very emblems of wealth Seidel enjoys are extracted through terrible violence, and point toward a future annihilation of his “tribe” (meaning the similarly affluent, meaning many of us Americans) and perhaps, of everything else. If you don’t believe me that Seidel senses doom—his and ours—, here’s how the poem ends:

The xylophone is playing too loud

Under the coconut palms, which go to the end of the world.

The slave is screaming too loud and we

Can’t help hearing

Our tribal chant and getting up to dance under the mushroom cloud.

Happy travels, reader.