Hilary Plum: “In the aftermath of our language”—On Hayan Charara’s Something Sinister

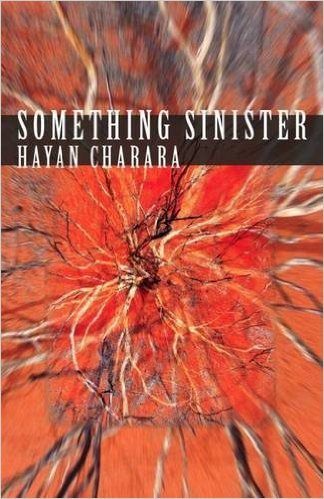

Something Sinister

Hayan Charara

Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2016

The achievement of Hayan Charara’s third book may be glimpsed in the opening lines to his long poem “Usage”:

An assumption, a pejorative, an honest language,

an honorable death. In grade school, I refused to accept

the mayor’s handshake; he smiled at everyone except

people with names like mine. I was born here.

I didn’t have to adopt America, but I adapted to it.

Swift on the heels of an “honest language,” we find an “honorable death.” Hope for the former must answer to the common lie of the latter. Too often the adjective “honorable” is cheap compensation for needless death in needless war; too often an “honest language” would only speak directly the racism the mayor confines to a glance. With compassionate precision, Charara sets these phrases alongside one another, and we remember their shared root, how in English “honesty” begins not in truth but in honor. Something Sinister works to restore honor to a language ruptured by the violence of the “war on terror” and the rhetoric aptly named “truthiness.” Charara accomplishes this through an ethics of closeness that preserves difference, an ethics suggested even in the small gesture above, “honest” and “honorable” echoing and challenging one another. What honesty can speak power to truthiness?

Throughout “Usage,” war and biography interrupt one another, the pulse of grammar vivifying both: “After the bombs fell, I called every night to find out / whether my father was alive or dead”; “Homeland Security Agents visited my house, / not once, not twice, but three times”; “Among all the names / for the dead … choose between ‘citizen’ and ‘terrorist.’” Through insistent emphasis, “Usage” reminds us that beside every linguistic choice, every act of signification, there is a possible error, a misusage. The error betrays you as one to whom the language does not belong, no matter if you were “born here.” The very complexity of language betrays a desire to identify those who would misuse it—a “who” that includes each “I” or “you” who steps forth into syntax. One needs no background in semiotics (a memory of grade school will do) to know this slipperiness: beside each word are myriad others—homophone, synonym, homonym, part of speech similar yet different—and one must ceaselessly distinguish among (not between) them. There is always the danger of adjacency, of not-quite; there is something sinister, the betrayal that could always yet occur: just as you would speak it, language speaks you. “Did language precede violence?,” Charara asks, “Can violence proceed / without language?”

Elsewhere in “Usage” Charara writes: “I spoke English with my father, he replied in Arabic. / Then I wondered, who’s to decide whose language it is / anyway—you, me?” Answers arrive not in the vocabulary of linguistic theory or workaday politics but in “the radio / interrupting the clamor of cicadas / with rumors of a truce // and the murders preceding it” (“The Trees”). The urgency and complexity of this question (“you, me?”) are made apparent in the book’s opening poem, “Being Muslim.” The title would seem to embrace the role of speaking on behalf of a collective identity, a role that contemporary politics thrusts upon someone who is, for example, a Muslim and Arab and American in the age of the “forever wars” or the “war on terror,” terms that have served to mask the racism of the violence they name. Yet having assumed the mantle of collective identity, the poem offers the personal, the intimately known: the poet’s father, who “worshipped” Muhammad Ali, who “loved being Muslim then. / Even when you drank whiskey. // Even when you knocked down / my mother again and again.” In the final stanzas, Charara evokes suras of the Qur’an (“Ta’ Ha’, Ya Sin, Sad, Qaf”) whose titular letters signify only themselves, their meanings lost or yet to arrive, and concludes, “God of my father, listen: / He prayed, he prayed, five times a day, // and he was mean.” This “and” refuses to reduce the father’s violence to a parable of hypocrisy; no single explanation may salvage it (as the book will address movingly when it considers the father’s entry into psychiatric discourse and medication). The external demands of identity (“Being Muslim”) neither cancel nor fulfill the scope and specificity of the personal (“O father bringing home crates / of apples, bushels of corn, and skinned rabbits on ice”). The poem “Being Muslim” refuses to yield the signification its title seems to promise; it calls up and out from (“O prayer”) the irreducible sensuousness and suffering of one life.

In the title poem, “Something Sinister Going On,” the poet speaks to or from or alongside a collective to which he may or may not believe he belongs. Such is this task that this “you,” this object of address and/or representation, of affiliation and/or unaffiliation, may change from one moment to the next. The tone is casual and colloquial, if “colloquial” includes forms of address most in the American colloquy would not attempt: toward those men—terrorists, radicals, fundamentalists? They are buried under many names—generally understood only in the rhetoric of violence. Often this violence is distant, but Charara approaches: “I’m one guy sitting in a chair, you’re a bunch of guys / on the street, screaming, chanting, / ‘Death to this’ and ‘Death to that.’ / You’re always so angry. / You should try being calm, letting go, own a pet, quit caffeine.” The advice is gentle, but much may be seen in this wry light. The poet draws nearer to this “bunch of guys,” if only to better know his distance from them:

We are one and the same.

We are getting close, at least.

Let me be clear about what is happening:

I’m here, you’re there—

The trees are blossoming—

Red birds flash past my window.

I can’t help but think of fire.

Images swiftly transmute: here the poet looks out the window—where he cannot, of course, see the men he addresses; they are not in fact “close”—and the blossoms on the trees are swiftly birds, are swiftly fire, then become “a mob, men holding matches to the trunks of trees, / a row of fire ants marching past.” The movement is associative, but as in “Usage,” the force driving the association is larger than the poet, arises out of the system of representation in which he lives and knows: visual and discursive slippages transform red bird to fire to fire ant. The poet sees and the language sees for him, a process that escalates until “A burning tree, you know, is like a redhead on fire.” By the end, agency has been won over by the image, and the poem concludes: “A fire speaks to a tree, the flame is patient— / it loves the tree to death.”

In this plain-spoken final line, we hear how close each noun is to (becoming) another; how easily the verb “love” may mean “kill.” “Now I have become you, and you me,” Charara says, a pronouncement that enacts both great compassion and real fear. The longer those men keep chanting, the longer the poet may be mistaken for them, and the less any distinctions will matter in the threatening conflagration. “You are making it impossible for me to live,” the poet says, with a note of patience, and in this line the “I”s and “you”s are, as ever, multiple. The careful use of articles in the poem’s final line testifies similarly: “a fire speaks to a tree.” The indefinite article resists polemic and insists on the immediacy of experience over the betrayal of meaning-making. “The fire” would be a historical event around which subjectivities and politics would stabilize; “a fire” is still anyone’s, could approach any of us, from here or there.

Perhaps Charara is the poet laureate of the indefinite article. Note the wrenching progression from “a dog” to “the family” in “Signs”: “A dog stopped barking // and this warned of heartache: / the hem of a blue dress, the bright // bare feet, the family discovered in a ditch.” Each image slides into an adjacent image: heartache is, comfortably enough, a woman’s dress; below the hem, suddenly, the aftermath of a larger violence. The movement here is like that of “Usage” but with the eye, not the ear. The problems of signification, of the singular and the multiple, are both near and ungraspable: “A man wonders if the moon // can still be written about. / A long time ago the moon was a mirror. // Men used it to decide marriages, to buy / cattle, to free captives, to dig graves.” A sign that all may read how they wish is no sign at all; yet this problem characterizes all signs, and the poem, of course, writes about the moon even as it questions this possibility. Charara is never content, though, to render the problems of language as such: the question of the sign is the question of how to “dig graves”; the question of “whose language” is the question of who survives. “Look. They’re animals,” the poem “Animals” concludes, with chilling directness: “Which is to say, there are also people. / And I haven’t even begun telling you / what was done to them.”

This book arrives into this, our time: its address (“Have you ever visited a training camp? / Did you pack your own bags?”) familiar—even if we have pretended otherwise—and its approach to the lyric subject vibrant across traditions (“Language written or translated into a single tongue / gives the illusion of tradition”). Charara offers a language honest enough for “you” and “I” to share, a book that honors both the question “What has history made of you?” and the answer, “It was always // like looking in the mirror— / that face is you. I am you.” Here we live together in the aftermath of our language, on any evening when “the weather on that day was a body floating in a street.”

—

Hilary Plum is the author of the work of nonfiction Watchfires (Rescue Press, 2016) and the novel They Dragged Them Through the Streets (FC2, 2013). Recent criticism has appeared in Full Stop, Bookforum, Music & Literature, and elsewhere. She lives in Philadelphia.